The Trees versus the Forest

by

Charles Lamson

During a typical month, the business and the financial pages of any leading newspaper or web site might include the following reports on the economy's recent performance: industrial production rose 1 percent; retail sales rose 2 percent; the unemployment rate fell slightly; IBM issued $300 million of bonds to finance the construction of a new plant; the Consumer Price Index increased 0.1 percent; the United Auto Workers and General Motors reached an agreement on a new three-year contract that will raise benefits and wages by 8 percent. The untrained eye might see little connection among these reports. The trained eye, however, sees more.

|

A major objective of any science---be it physics, astronomy, or economics---is to find patterns where the untrained eye sees only disorder. To discover and understand these patterns, it is usually necessary to disregard inessential details. Such abstraction facilitates the identification of the fundamental and essential relationships linking the key elements of the process or the phenomena being studied.

In the study of money, credit, and the financial system, you may find the details of the analysis overwhelming. Unfortunately, they may obscure the broad fundamental patterns of order so important to an analytical foundation. The problem is akin to getting lost in a forest. By paying too much attention to the individual trees, you can become disoriented and lose your way.

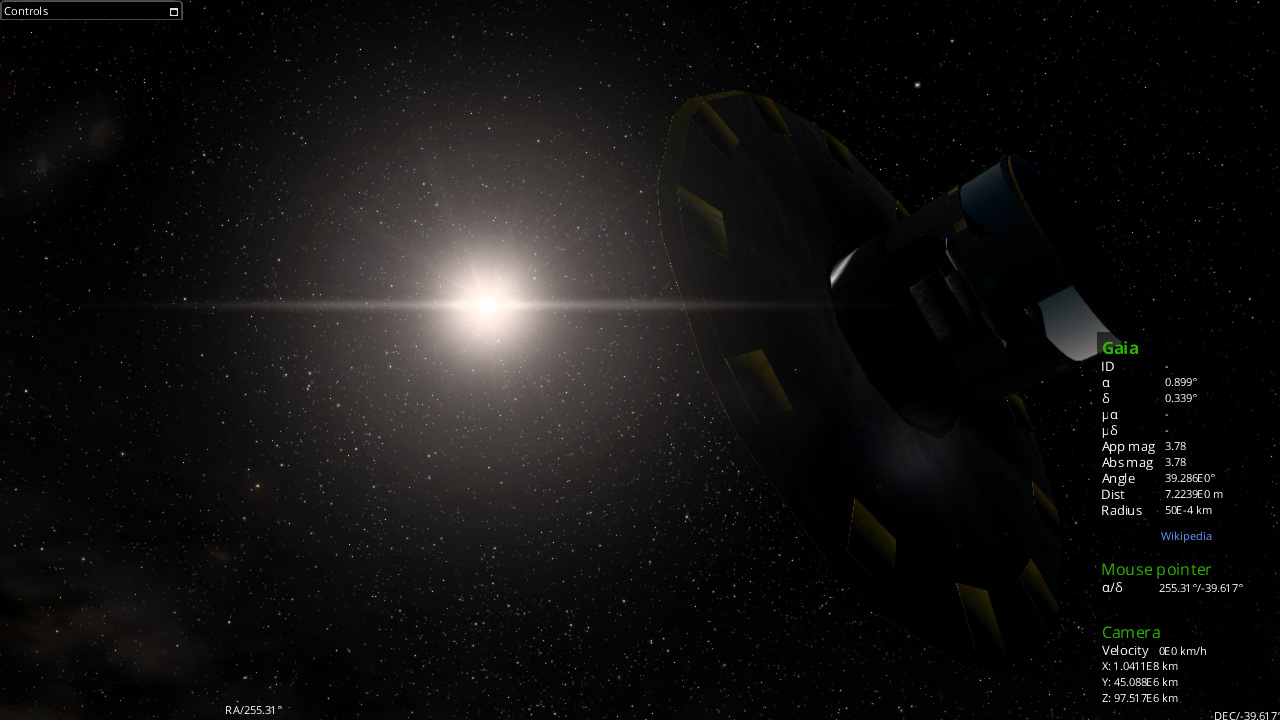

The general purpose of this next series of articles, in which, I will be analyzing the book The Financial System & the Economy by Maureen Burton and Ray Lombra, is to provide an analytical perspective on how the financial system fits in the overall economy. The circular flow analysis and accompanying diagrams should serve both as a roadmap through the economic "forest," and as an aerial photograph that reveals the patterns of order that link households, firms, financial markets, and financial intermediaries.

Spending, Saving, Borrowing, and Lending

It is important here, to better understand this next series of articles, that we define surplus spending units (SSUs) and deficit spending units (DSUs). SSUs spend less than their current income during a particular period of time. More precisely, the surplus is the income that spending units receive, but do not spend on consumer goods and services, or on investments such as new houses. It is this surplus that SSUs have available to lend. The spending units that spend more than their current income during a particular period of time are DSUs. The deficit is the extent of current spending on goods and services and investments over current income.

The DSUs must finance their deficits in some way. Normally, they do so by borrowing. Some DSUs, such as business firms, accomplish this by issuing financial claims on themselves. For now, we will refer to these financial claims on DSUs as bonds. Other types of DSUs, such as students struggling to buy books, pay their tuition, and feed themselves, may finance their deficits by taking out loans from their local banks. These loans too are a type of financial claim; the students agree to repay the loan principal plus interest.

Who provide the funds that the DSUs receive when they issue bonds, and the funds that banks lend to students? The answer, of course, the SSUs. Rather than accumulating the surpluses in the form of cash assets, buried in their back yards or hidden under their mattresses, SSUs generally purchase interest-earning financial claims. For example, a household with a surplus might purchase a bond issued by a corporation. Likewise, the household might deposit the funds in a savings account at a bank, which in turn lends them to the DSUs. Thus, the SSUs are the lenders in society, and the financial system, composed of the financial markets and financial intermediaries, channels the surpluses of SSUs to the DSUs to finance their deficits.

To sum up to this point, individual spending units make two types of decisions. First, they decide whether to be DSUs or SSUs. Second if they decide to be DSUs, they must decide how to finance their deficits. If they decide to be SSUs, they must decide what to do with their surpluses. The financial system channels and coordinates the flow of funds, resulting from these decisions made by individual spending units.

*SOURCE: THE FINANCIAL SYSTEM & THE ECONOMY, THIRD EDITION, 2003, MAUREEN BURTON, PGS. 62-63*

END

|