Externalities, Public Goods, Imperfect Information, and Social Choice

(Part A)

by

Charles Lamson

So far in this analysis, we built a complete model of a perfectly competitive economy under a set of assumptions; we had demonstrated that the allocation of resources under perfect competition is efficient, and we began to relax some of the assumptions on which the perfectly competitive model is based; we introduced the idea of market failure, and most recently we talked about three kinds of imperfect markets: monopoly, oligopoly, and monopolistic competitive competition. We also discussed some of the ways government has responded to the inefficiencies of imperfect markets and to the development of market power.

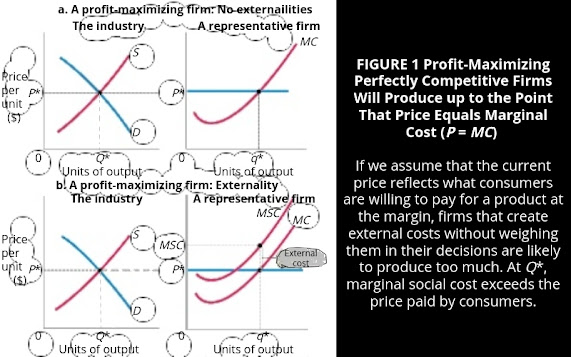

As we continue our examination of market failure, we look first at externalities as a source of inefficiency. Often when we engage in transactions or make economic decisions, second or third parties suffer consequences that decision-makers have no incentive to consider. For example, for many years manufacturing firms and power plants had no reason to worry about the impact of smoke from their operations on the quality of the air we breathe. Now we know that air pollution---an externality---harms people. Next, we consider a second type of market failure that involves products private firms find unprofitable to produce even if members of society want them. These products are called public goods or social goods. Public goods yield collective benefits, and in most societies, governments produce them or arrange to provide them. The process of choosing what social goods to produce is very different from the process of private choice. A third source of market failure is imperfect information. When information is imperfect, misallocation of resources may result. Finally, while the existence of public goods, externalities, and imperfect information are examples of market failure, it is not necessarily true that government involvement will always improve matters. Just as markets can fail, so too can governments. When we look at the incentives facing government decision makers, we find several reasons behind government failure. Externalities and Environmental Economics An externality exists when the actions or decisions of one person or group impose a cost or bestow a benefit on second or third parties. Externalities are sometimes called spillovers or neighborhood effects. Inefficient decisions result when decision makers fail to consider social costs and benefits. The presence of externalities is a significant phenomenon in modern life. Examples are everywhere: air, water, land, sight, and sound pollution; traffic congestion; automobile accidents; abandoned housing; nuclear accidents; and secondhand cigarette smoke are only a few. The study of externalities is a major concern of environmental economics. The opening of Eastern Europe in 1989 and 1990 revealed that environmental externalities are not limited to free market economies. Part of the logic of a planned economy is that when economic decisions are made socially (by the government, presumably acting on behalf of the people) instead of privately, planners can and will take all costs---private and social---into account. This has not been the case, however. When east and west Germany were reunited and the borders of Europe were opened, we saw the disastrous condition of the environment in virtually all Eastern Europe. As societies become more urbanized, externalities become more important: when we live closer together, our actions are more likely to affect others. Marginal Social Cost and Marginal Cost Pricing Profit-maximizing perfectly competitive firms will produce output up to the point at which price is equal to marginal cost (P = MC). Let us take a moment here to review why this is essential to the proposition that perfectly competitive markets produce what people want---an efficient mix of output. When a firm weighs price and marginal cost and externalities exist, it is weighing the full benefits to society of additional production against the full costs to society of that production. Those who benefit from the production of a product are the people or households who end up consuming it. The price of a product is a good measure of what an additional unit of that product is "worth," because those who value it more highly already buy it. People who value it less than the current price are not buying it. If marginal cost includes all costs---that is, all costs to society of producing a marginal unit of a good, then additional production is efficient, provided that P is greater than MC. Up to the point where P = MC, each unit of production yields benefits in excess of cost. Consider a firm in the business of producing laundry detergent. As long as the price per unit that consumers pay for that detergent exceeds the cost of the resources needed to produce one marginal unit of it, the firm will continue to produce. Producing up to the point where P = MC is efficient, because for every unit of detergent produced, consumers derive benefits that exceed the cost of the resources needed to produce it. Producing at a point where MC is greater than P is inefficient, because marginal cost will rise above the unit price of the detergent. For every unit produced beyond the level at which P = MC, society uses up resources that cost more than the benefits that consumers place on detergent. Figure 1(a) shows a firm in an industry in which no externalities exist. Suppose, however, that the production of the firm's product imposes external costs on society as well. If it does not factor those additional costs into its decision the firm is likely to overproduce. In Figure 1(b), a certain measure of external costs is added to the firm's marginal cost curve. We see these external costs in the diagram, but the firm is ignoring them. The curve labeled MSC, marginal social cost, is the sum of the marginal costs of producing the product plus the correctly measured damage costs imposed in the process of production. If the firm does not have to pay for these damage costs, it will produce exactly the same level of output (q*) as before, and price (P*) will continue to reflect only the costs that the firm actually pays to produce its product. The firms in this industry will continue to produce, and consumers will continue to consume their product, but the market price takes into account only part of the full cost of producing the good. At equilibrium (q*), marginal social costs are considerably greater than price. Price is a measure of the full value to consumers of a unit of the product at the margin. Decision makers at the manufacturing firms and public utilities weigh these costs, but there is another side to this story. Burning cheap coal and not worrying about the acid rain that may be falling on someone else means jobs and cheap power for residents of the Midwest. Forcing coal-burning plants to pay for past damages from acid rain and even requiring them to weigh the costs that they are presently imposing undoubtedly raises electricity prices and production costs in the Midwest. Some firms have been driven out of business and some jobs have been lost. However, if the electricity and other products produced in the Midwest are worth the full costs imposed by acid rain, plants would not shut down; consumers would pay higher prices. If those goods are not worth the full cost, they should not be produced. The case of acid rain highlights the fact that efficiency analysis ignores the distribution of gains and losses. That is, to establish efficiency we need only to demonstrate that the total value of the gains exceeds the total value of the losses. If Midwestern producers and consumers of their products were forced to pay an amount equal to the damages they caused, the gains from damage in the East and in Canada would be at least as great as costs in the Midwest. The beneficiaries of forcing Midwestern firms to consider these costs would be the households and firms in the East and in Canada. After many years of debate, Congress passed and President Bush signed the Clean Air Act of 1990. Included in the law are strict emissions standards aimed, in part, at controlling the production and distribution of acid rain. An interesting provision of the Clean Air Act is its use of "tradable pollution rights," which we discuss in a later post. Other Externalities Other examples of external effects are all around us. When you drive your car into the center of the city at rush hour, you contribute to the congestion and impose costs (in the form of lost time and auto emissions) on others. One focus of environmental activists is the possibility of worldwide climate warming as a result of "greenhouse emissions" (like carbon dioxide) from industrial plants and automobiles. While potential costs are high, great uncertainty, both in the scientific evidence and in the magnitude of the potential costs, surrounds the issue. Secondhand cigarette smoke has become a matter of public concern. In December 1994, a judge in Florida ruled that nonsmokers could bring a class action suit based on the health consequences of passive smoke. Smoking has been banned on domestic air carriers, and many states have passed laws severely restricting smoking in public places. In 1997, the big tobacco firms initiated an agreement to pay over $350 billion to compensate those harmed by smoke and to reimburse states for smoking-related medicinal expenses paid under the Medicaid program. Despite these problems, not all externalities are negative: An abandoned house in an urban neighborhood that is restored and occupied makes the neighborhood better and adds value to the neighbors' homes. *CASE & FAIR, 2004, PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS, 7TH ED., PP. 305-308* end |

%20(3)%20(1)%20(1)%20(5)%20(2)%20(1)%20(3)%20(3)%20(1)%20(2)%20(1)%20(2)%20(2)%20(2)%20(3)%20(4)%20(1)%20(2).jpg)