― Joseph E. Stiglitz

Monopoly and Antitrust Policy

(Part D)

by

Charles Lamson

The Social Costs of Monopoly

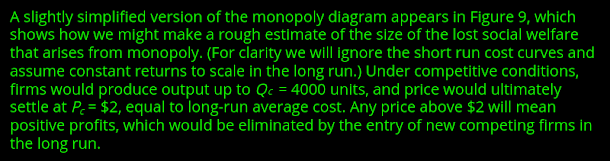

So far we have seen that a monopoly produces less output and charges a higher price than a competitively organized industry, if no large economies of scale exist for the monopoly. You are probably thinking at this point that producing less and charging more to earn positive profits is not likely to be in the best interests of consumers, and you are right. Inefficiency and Consumer Loss In an earlier post, we argued that price must equal marginal cost (P = MC) for markets to produce what people want. This argument rests on two propositions: (1) that price provides a good approximation of the social value of a unit of output, and (2) that marginal cost, in the absence of externalities (costs or benefits to external parties not weighed by firms), provides a good approximation of the product's social opportunity cost. In a pure monopoly, price is above the product marginal cost. When this happens, the firm is under producing from society's point of view; society would be better off if the firm produced more and charged a lower price. We can, therefore, conclude that monopoly leads to an inefficient mix of output. Now consider the gains and losses associated with increasing price $2 to $4 and cutting output from 4,000 units to 2,000 units. As you might guess, the winner will be the monopolist and the loser will be the consumer, but let us see how it works out. Now the industry is reorganized as a monopoly that cuts output to 2,000 units and raises price to $4. The big winner is the monopolist, who ends up earning profits equal to $4,000. Of course, monopolies may have social costs that do not show up on these diagrams. Monopolies, which are protected from competition by barriers to entry, do not face the same pressures to cut costs and to innovate as competitive firms do. A competitive firm that does not use the most efficient technology will be driven out of business by firms that do. One of the significant arguments against tariffs and quotas to protect such industries as automobiles and steel from foreign competition is that protection removes the incentive to be efficient and competitive. Rent-Seeking Behavior There are many things that potential monopolists can do to protect their profits. One obvious approach is to push the government to impose restrictions on competition. A classic example is the behavior of taxicab driver organizations in New York and other large cities. To operate a cab legally in New York City, you need a license. The city tightly controls the number of licenses available. If entry into the taxi business were open, competition would hold down cab fares to the cost of operating cabs. However, cab drivers have become a powerful lobbying force and have muscled the city into restricting the number of licenses issued. This restriction keeps fares high and preserves monopoly profits. There are countless other examples. The steel industry and the automobile industry spend large sums lobbying Congress for tariff protection. Some experts claim that both the establishment of the now-defunct Civil Aeronautics Board in 1937 to control competition in the airline industry and the extensive regulation of trucking by the FTC prior to deregulation in the 1970s came about partly through industry efforts to restrict competition and preserve profits. This kind of behavior, in which households or firms take action to preserve positive profits, is called rent-seeking behavior. Rent is the return to a factor of production in strictly limited supply. Rent-seeking behavior has two important implications. First, this behavior consumes resources. Lobbying and building barriers to entry are not costless activities. Lobbyists' wages, expenses of the regulatory bureaucracy, and the like must be paid. With the prospect that the city of New York will issue new taxi licenses, cab owners and drivers have become so well-organized that they can bring the city to a standstill with a strike or even a limited job action. Indeed, positive profits may be completely consumed through rent-seeking behavior that produces nothing of social value; all it does is help to pressure the current distribution of income. Second, the frequency of rent-seeking behavior leads us to another view of government. So far we have considered only the role that government might play in helping to achieve an efficient allocation of resources in the face of market failure---in this case, failures that arise from imperfect market structure. In a later post we survey the measures government might take to ensure that resources are efficiently allocated when monopoly power arises. However, the idea of rent-seeking behavior introduces the notion of government failure, in which the government becomes the tool of the rent seeker, and the allocation of resources is made even less efficient than before. This idea of government failure is at the center of public choice theory, which holds that governments are made up of people, just as business firms are. These people---politicians and bureaucrats---can be expected to act in their own self-interest, just as the owners of firms do. We turn to the economics of public choice in a later post. *CASE & FAIR, 2004, PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS, 7TH ED., PP. 265-268* end |

No comments:

Post a Comment