1st half: Alfred Marshall's Principles of Economics

2nd half: Timely top stories in the world of finance, featuring interviews with Andreesen Horowitz and Meltem Demiror

Mission Statement

The Rant's mission is to offer information that is useful in business administration, economics, finance, accounting, and everyday life. The mission of the People of God is to be salt of the earth and light of the world. This people is "a most sure seed of unity, hope, and salvation for the whole human race." Its destiny "is the Kingdom of God which has been begun by God himself on earth and which must be further extended until it has been brought to perfection by him at the end of time."

Friday, November 29, 2019

Thursday, November 28, 2019

Managing for Competitive Advantage (part 13)

Leadership (part B)

by

Charles Lamson

Traditional Approaches to Understanding Leadership

Three traditional approaches to studying leadership are the trait approach, the behavioral approach, and the situational approach.

|

Leader Traits

The trait approach is the oldest leadership perspective and was dominant for several decades. This approach seems logical for studying leadership because it focuses on individual leaders and attempts to determine the personal characteristic traits that great leaders share. What set Winston Churchill, Alexander the Great, Gandhi, Napoleon, and Martin Luther King apart from the crowd? The trait approach assumes the existence of a leadership personality and assumes that leaders are born, not made.

From 1904 to 1948, over 100 leadership trait studies were conducted. At the end of that period, management scholars concluded that no particular set of traits is necessary for a person to become a successful leader. Enthusiasm for the trait approach diminished, but some research on traits continued. By the mid-1970s, a more balanced view emerged although no traits ensure leadership success, certain characteristics are potentially useful. The current perspective is that some personality characteristics---many of which a person need not be born with but can strive to acquire---do distinguish effective leaders from other people.

2. Leadership motivation. Great leaders not only have drive; they want to lead. They have a high need for power, preferring to be in leadership rather than follower positions. A high power need induces people to attempt to influence others, and sustains interest and satisfaction in the process of leadership. When the power need is exercised in moral and socially constructive ways, rather than to the detriment of others, leaders Inspire more trust, respect, and commitment to their vision.

3. Integrity. Integrity is the correspondence between actions and words. Honesty and credibility, in addition to being desirable characteristics in their own right, are especially important for leaders because these traits inspire trust in others.

4. Self confidence. Self confidence is important for a number of reasons. The leadership role is challenging, and setbacks are inevitable. Self-confidence allows a leader to overcome obstacles, make decisions despite uncertainty, and instill confidence in others.

5. Knowledge of the business. Effective leaders have a high level of knowledge about their industries, companies, and technical matters. Leaders must have the intelligence to interpret vast quantities of information. Advanced degrees are useful in a career, but ultimately less important than acquired expertise and matters relevant to the organization.

Finally, there is one personal skill that may be the most important: the ability to perceive the needs and goals of others and to adjust one's personal leadership approach accordingly. Effective leaders do not rely on one leadership style, rather, they are capable of using different styles as the situation warrants. This quality is the cornerstone of the situational approaches to leadership, which we will discuss shortly.

Leader Behaviors

The behavioral approach to leadership attempts to identify what good leaders do. Should leaders focus on getting the job done or in keeping their followers happy? Should they make decisions autocratically or democratically? In the behavioral approach, personal characteristics are considered less important than the actual behaviors leaders exhibit.

Three General categories of leadership behavior have received particular attention: behaviors related to task performance, group maintenance, and employee participation in decision-making.

Task Performance Leadership requires getting the job done. Task performance behaviors are the leaders efforts to ensure that the work unit or organization reaches its goals. This dimension is variously referred to as concern for production, directive leadership, initiating structure, or closeness of supervision. It includes focus on work, quality and accuracy, quantity of output, and following the rules.

Group Maintenance In exhibiting group maintenance behaviors, leaders take action to ensure the satisfaction of group members, develop and maintain harmonious work relationships, and preserve the social stability of the group. This dimension is sometimes referred to as concern for people, supportive leadership, or consideration. It includes a focus on people's feelings and comfort, appreciation of them, and stress reduction.

One theory of leadership, Leader Member Exchange (LMX) theory, highlights the importance of leader behaviors not just toward the group as a whole but toward individuals on a personal basis. The focus is primarily on the leader behaviors historically considered group maintenance. According to LMX theory, and as supported by research evidence, maintenance behaviors such as trust, open communication, mutual respect, mutual obligation, and mutual loyalty form the cornerstone of relationships that are satisfying and perhaps more productive.

Remember though, the potential for cross-cultural differences. Maintenance behaviors are important everywhere, but the specific behaviors can differ from one culture to another. For example, in the United States, maintenance behaviors include dealing with people's face-to-face; in Japan, written memos are preferred over giving directions face-to-face; thus avoiding confrontation and permitting face-saving in the events of disagreement.

Participation in Decision-Making How should a leader make decisions? More specifically, to what extent should leaders involve their people in making decisions? The participation in decision-making dimension of leadership behavior can range from autocratic to democratic. Autocratic leadership makes decisions and then announces them to the group. Democratic Leadership solicits input from others. Democratic leadership seeks information, opinions, and preferences, sometimes to the point of meeting with the group, leading discussions, and using consensus or majority vote to make the final choice.

The Effects of Leader Behavior How the leader behaves influences people's attitudes and performance. Studies of these effects focus on autocratic versus democratic decision styles or on performance- versus maintenance-oriented behaviors.

Decision Styles The classic study comparing autocratic and democratic styles found that a democratic approach resulted in the most positive attitudes, whereas an autocratic approach resulted in somewhat higher performance. A laissez-faire style, in which the leader essentially made no decision, led to more negative attitudes and lower performance. These results seem logical and probably represent the prevalent beliefs among managers about the general effects of these decision-making approaches.

Democratic styles, appealing though they may seem, are not always the most appropriate. When speed is of the essence, democratic decision-making may be too slow, or people may demand decisiveness from the leader. Whether a decision should be made autocratically or democratically depends on the characteristics of the leader, the followers, and the situation. Thus, a situational approach to leader decision styles, discussed later in this post, is appropriate.

Performance and Maintenance Behaviors The performance and maintenance dimensions of leadership are independent of each other. In other words, a leader can behave in ways that emphasize one, both, or neither of these dimensions. Some Research indicates that the ideal combination is to engage in both types of leader behaviors.

In the well-known Ohio State studies, a team of the Ohio State University researchers investigated the effects of leader behaviors in a truck manufacturing plant of International Harvester. Generally, supervisors who were high on maintenance behaviors (which the researchers termed consideration) had fewer grievances and less turnover in their work units than supervisors who were low on this dimension. The opposite held for task performance behaviors (which the team called initiating structure). Supervisors high on this dimension had more grievances and higher turnover rates (E. Fleischman and E. Harris, "Patterns of Leadership Behavior Related to Employee Grievances and Turnover," Personal Psychology 15 (1962), pp. 43-56).

When maintenance and performance leadership behaviors were considered together, the results were more complex. But one conclusion was clear: When a leader must be high on performance-oriented behaviors, he or she should also be maintenance oriented. Otherwise the leader will have employees with high rates of turnover and grievances.

At about the same time the Ohio Studies were being conducted, an equally famous research program at the University of Michigan was studying the impact of the same leader behaviors on groups' job performance. Among other things, the researchers concluded that the most effective managers engaged in what they called task-oriented behavior: planning, scheduling, coordinating, providing resources, and setting performance goals. Effective managers also exhibited more relationship-oriented: behavior demonstrating trust and confidence, being friendly and considerate, showing appreciation, keeping people informed, and so on. These dimensions of leader Behavior are essentially the task performance and group maintenance dimensions. (R. Likert, The Human Organization: Its Management and Value (1967)).

A wide range of effective leadership styles exist. Organizations that understand the need for diverse leadership styles will have a competitive advantage in the modern business environment over those that believe there is only one best way.

Situational Approaches to Leadership

According to proponents of the situational approach to leadership, universally important traits and behaviors do not exist. They believe effective leader behaviors vary from situation to situation. The leaders should first analyze the situation and then decide what to do. In other words, look before you leap.

The first situational model of leadership was proposed in 1958 by Tannenbaum and Schmidt. In their classic Harvard Business Review article, these authors describe how managers should consider three factors before deciding how to lead: forces in the manager, forces in the subordinate, and forces in the situation. Forces in the subordinate include the employee's knowledge and experience, readiness to assume responsibility for decision-making, interest in the task or problem, and understanding and acceptance of the organization's goals. Forces in the situation include the type of leadership style the organization values, the degree to which the group works effectively as a unit, the problem itself and the type of information needed to solve it, and the amount of time the leader has to make the decision (Tannenbaum & Schmidt, "How to Choose a Leadership Pattern").

Path-Goal Theory Perhaps the most generally useful situational model of leadership effectiveness is path-goal theory. Developed by Robert house, Path-goal gets its name from its concern with how leaders influence followers perceptions of their work goals and the paths they follow toward goal attainment. (R.J. House, "A Path-Goal Theory of Leader Effectiveness." Administrative Science Quarterly 16 (1971), pp. 321-39.)

The key situational factors in path-goal theory are (1) personal characteristics of followers, and (2) environmental pressures and demands with which followers must cope to attain their work goals. These factors determine which leadership behaviors are most appropriate.

The four pertinent leadership behaviors are: (1) directive leadership, a form of task performance-oriented behavior; (2) supportive leadership, a form of group maintenance-oriented behavior; participative leadership, or decision style; and (4) achievement-oriented leadership, or behaviors geared toward motivating people, such as setting challenging goals and rewarding good performance.

These situational factors and leader behaviors are merged in Figure 1. As you can see, appropriate leader behaviors---as determined by characteristics of followers and the work environment---lead to effective performance.

FIGURE 1 The Path-Goal Framework

The theory also specifies which follower and environmental characteristics are important. There are three key follower characteristics. Authoritarianism is the degree to which individuals respect, admire, and defer to Authority. Locus of control is the extent to which individuals see the environment as responsive to their own behavior. People with an internal locus of control believe that what happens to them is their own doing. People with an external locus of control believe that it is just luck or fate. Finally, abilities is people's beliefs about their own abilities to do their assigned jobs.

Path-goal theory states that these personal characteristics determine the appropriateness of various leadership styles. For example, the theory makes the following propositions:

Appropriate leadership style is also determined by three important environmental factors: people's tasks, the formal authority system of the organization, and the primary work group.

Path-goal Theory offers many more propositions. In general, the theory suggests that the functions of the leader are to (1) make the path to work goals easier to travel by providing coaching and direction; (2) reduce frustrating barriers to goal attainment; and (3) increase opportunities for personal satisfaction by increasing payoffs to people for achieving performance goals.

How best to do these things depends on your people and on the work situation. Again: Analyze, then adapt your style accordingly.

Substitutes for Leadership Sometimes leaders do not have to lead, or situations constrain their ability to lead effectively. The situation may be one in which leadership is unnecessary or has little impact. Substitutes for leadership can provide the same influence on people that leaders otherwise would have.

Certain follower, task, and organizational factors are substitutes for task performance-oriented and group maintenance-oriented leader behaviors. For example, group maintenance behaviors are less important and have less impact if people already have a close-knit group, they have a professional orientation, the job is intrinsically satisfying, or there is great physical distance between leader and followers. Physicians who are strongly concerned with professional conduct, enjoy their work, and work independently do not need social support from hospital administrators.

Task performance leadership is less important and will have less of a positive effect if people have a lot of experience and ability; feedback is supplied to them directly from the task or by computer, or the rules and procedures are rigid. If these factors are operating, the leader does not have to tell people what to do or how well they are performing.

The concept of substitutes for leadership does more than indicate when a leader's attempts at influence will and will not work. It provides useful and practical prescriptions for how to manage more efficiently. If the manager can develop the work situation to the point where a number of these substitutes for leadership are operating, less time will need to be spent in direct attempts to influence people. The leader will be free to spend more time on other important activities.

*SOURCE: MANAGEMENT: THE NEW COMPETITIVE LANDSCAPE, 6TH ED., 2004, THOMAS S. BATEMAN & SCOTT A. SNELL, PGS. 371-382*

end

|

Wednesday, November 27, 2019

Tuesday, November 26, 2019

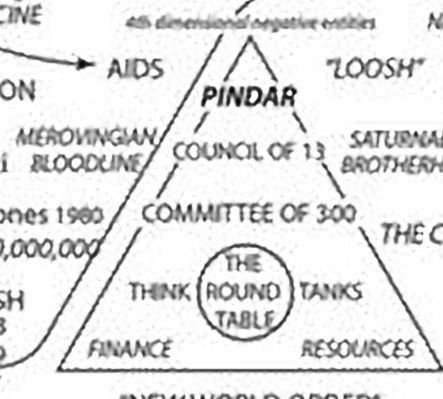

Pindar - Reptoid Ruler of Earth

Managing for Competitive Advantage (part 12)

Leadership

by

Charles Lamson

People get excited about the topic of leadership. They want to know: What makes a great leader? Executives at all levels in all Industries are interested in this question. They believe the answer will bring improved organizational performance and personal career success. They hope to acquire the skills that will transform an average manager into a true leader.

|

Fortunately, leadership can be taught and learned. Leadership seems to be the marshalling of skills possessed by a majority but used by a minority. However, it is something that can be learned by anyone, taught to everyone, denied to no one.

What is leadership? To start, a leader is one who influences others to attain goals. The greater the number of followers, the greater the influence. And the more successful the attainment of worthy goals, the more evident the leadership. But we must explore beyond this bare definition to capture the excitement and intrigue that devoted followers and students of leadership feel when they see a great leader in action.

Outstanding leaders formulate and implement strategies that produce results and sustainable competitive advantage. They may launch enterprises, build organization cultures, win wars, or otherwise change the course of events. They are strategists who sieze opportunities others overlook, but they are also passionately concerned with detail---all the small, fundamental realities that can make or mar the grandest of plans.

Vision

The leader's job is to create a vision. Until a few decades ago, vision was not a word one heard managers utter. But today, having a vision for the future and communicating that vision to others are known to be essential components of great leadership. If there is no vision, there is no business. Leaders are painters of the vision and archetypes of the journey. A clear vision and communication of that vision leads to higher venture growth in entrepreneurial firms.

A vision is a mental image of a possible and desirable future state of the organization. It expresses the leader's ambitions for the organization. The best visions are both ideal and unique. If a vision conveys an ideal, it communicates a standard of excellence and a clear choice of positive values. If the vision is also unique, it communicates and inspires pride in being different from other organizations. The choice of language is important; the words should imply a combination of realism and optimism, an action orientation, and resolution and confidence that the vision will be attained.

Great leaders imagine an ideal future for their organization that goes beyond the ordinary and beyond what others may have thought possible. They strive to realize significant achievements that others have not. In short, leaders must be forward-looking and clarify the direction in which they want their organizations, and even entire industries, to move.

Visions can be small or large and can exist throughout all organizational levels as well as at the very top. The important points are that (1) a vision is necessary for effective leadership; (2) a person or team can develop a vision for any job, work unit, or organization; and (3) many people, including managers who do not develop into strong leaders, do not develop a clear vision---instead, they focus on performing or surviving on a day-to-day basis.

Put another way, leaders must know what they want. And other people must understand what that is. The leader must be able to articulate the vision, clearly and often. Other people throughout the organization should understand the vision and be able to state it clearly themselves. That's a start. But the vision means nothing until the leader and followers take action to turn the vision into reality.

Two metaphors reinforce the important concept of vision. The first is the jigsaw puzzle. It is much easier to put a puzzle together if you have the picture on the box cover in front of you. Without the picture, or vision, the lack of direction is likely to result in frustration and failure. The second metaphor is the slide projector. Imagine a projector that is out of focus. If you had to watch blurred images for a long period of time, you would get confused, and impatient, and disoriented. You would stop following the presentation and lose respect for the presenter. It is the leader's job to focus the projector. That is what communicating a vision is all about: making it clear where you are heading.

Not just any vision will do. Visions can be inappropriate and even fail for a variety of reasons. First, an inappropriate vision may reflect merely the leader's personal needs. Such a vision can be unethical, or may fail because of lack of acceptance by the market or by those who must implement it.

Second (and related to the first), an inappropriate vision may ignore stakeholder needs. Third, the leader must stay abreast of environmental changes. Although effective leaders maintain confidence and persevere despite obstacles, the time may come when the facts dictate that the vision must change. You will learn more about change and how to manage it later in this analysis.

Leading and Managing

Effective managers are not necessarily true leaders. Many administrators, supervisors, and even top executives execute their responsibility successfully without being great leaders. But these positions afford opportunity for leadership. The ability to lead effectively, then, will set the excellent managers apart from the average ones.

Whereas management must deal with the ongoing, day-to-day complexities of organizations, true leadership includes effectively orchestrating important change. While managing requires planning and budgeting routines, leading includes setting the direction (creating a vision) for the firm. Management requires structuring the organization, staffing it with capable people, and monitoring activities. Leadership goes beyond these functions by inspiring people to attain the vision. Great leaders keep people focused on moving the organization toward its ideal future, motivating them to overcome whatever obstacles lie in the way.

Many observers decry the rarity of strong leadership. While many managers focus on superficial activities and worry about short-term profits and stock prices, too few have emerged as leaders who foster innovation and the attainment of long-term goals. And whereas many managers are overly concerned with fitting in and not rocking the boat, those who emerge as leaders are more concerned with making important decisions that may break with tradition but are humane, moral, and right. The leader puts a premium on substance rather than on style.

It is important to be clear here about several things. First, management and leadership are both vitally important. To highlight the need for more leadership is not to minimize the importance of management for managers. It is to say that leadership involves unique processes that are distinguishable from basic management processes. Moreover, just because they involve different processes does not mean that they require different, separate people. The same individual can exemplify effective managerial processes, leadership processes, both, or neither.

Some people will dislike the idea of distinguishing between management and leadership, maintaining it is artificial or derogatory toward the managers and management processes that make organizations run. Perhaps a better or more useful distinction is between supervisory and strategic leadership. Supervisory leadership is behavior that provides guidance, support, and coercive feedback for the day-to-day activities of work unit members. Strategic leadership gives purpose and meaning to organizations. Strategic leadership involves anticipating and envisioning a viable future for the organization, and working with others to initiate changes that create such a future.

*SOURCE: MANAGEMENT: THE NEW COMPETITIVE LANDSCAPE, 6TH ED., 2004, THOMAS S. BATEMAN & SCOTT A. SNELL, PGS. 366-368*

end

|

Monday, November 25, 2019

My Two-Hour In-Depth Interview on the Mona Radler Show on Revolution Radio 11/25 by CharlesXLamson | Current Events

My Two-Hour In-Depth Interview on the Mona Radler Show on Revolution Radio 11/25 by CharlesXLamson | Current Events: In this episode of The Rant, I do a simulcast of me being interviewed by Mona Radler ('The Feral Hippy') on her show on Revolution Radio.

Sunday, November 24, 2019

Wednesday, November 20, 2019

Managing for Competitive Advantage (part 11)

The Rant with Charles Lamson is completely audience supported. To donate, please mail check, cash, or money order to:

Charles Lamson

1203 Fox Chase Dr.

St. Charles, MO 63301

You are the fuel that keeps this machine rolling!

The Responsive Organization

by

Charles Lamson

Organizing for Environmental Response

Apart from organizing for optimal size, organizations have to adapt to external environments. In a sense, this is the crux of creating a responsive organization. There are various approaches organizations might take to respond to the environment. They included adapting to the environment, influencing the environment, and selecting a new environment. In this section, we want to delve more deeply into how organizations organize for environmental response.

Organizing for Customer Responsiveness

The environment is composed of many different parts (government, suppliers, competitors, and the like). Perhaps no other aspect of the environment has had a more profound impact on organizing in recent years then a focus on customers. Dr Kenichi Ohmae points out that any business unit must take into account three key players: the company itself, the competition, and the customer. These components form what Ohmae a refers to as the strategic triangle, as shown in Figure 1. Managers need to balance the strategic triangle and successful organizations use their strengths to create value by meeting customer requirements better than competitors do.

FIGURE 1 The Strategic Triangle

Customer Relationship Management CRM Customer relationship management is a multifaceted process, typically mediated by a set of information technologies, that focuses on creating two-way exchanges with customers so that firms have an intimate knowledge of their needs, wants, and buying patterns. In this way, CRM helps companies understand, as well as anticipate, the needs of current and potential customers. And in that way, it is part of a business strategy for managing customers to maximize their long-term value to an enterprise.

As discussed throughout this analysis, customers want quality goods and services, low cost, innovative products, and speed. Traditional thinking considered these basic customer wants as a set of potential trade-offs. For instance, customers wanted high quality or low costs passed along in the form of low prices. But world-class companies today know that the “trade-off” mentality no longer applies. Customers want it all, and they are learning that somewhere an organization exists that will provide it all.

But if all companies seek to satisfy customers, how can a company realize a competitive advantage? World-class companies have learned that almost any advantage is temporary, for competitors will strive to catch up. Simply stated---though obviously not simply done---a company attains and retains competitive advantage by continuing to improve. This concept---kaizen, or continuous improvement---is an integral part of Japanese operations strategy. Motorola, a winner of the Malcolm Bridge National Quality Award, operates with the philosophy that “the company that is satisfied with its progress will soon find that its customers are not.”

As organizations focus on responding to customer needs, they soon find that traditional meaning of a customer expands to include “internal customers.” The word customer now refers to the next process, or wherever the work goes next. This highlights the idea of interdependence among related functions and means that all functions of the organization---not just marketing people---have to be concerned with customer satisfaction. All recipients of the person's work, whether co-worker, boss, subordinate, or external party, come to be viewed as the customer.

Total Quality Management (TQM) Total quality management is a way of managing in which everyone is committed to continuous improvement of his or her part of the operation. In business, success depends on having quality products. TQM is a comprehensive approach to improving product quality and thereby customer satisfaction. It is characterized by a strong orientation toward customers (external and internal) and has become an umbrella theme for organizing work. TQM reorients managers toward involving people across departments in improving all aspects of the business. Continuous Improvement requires integrated mechanisms that facilitate group problem-solving, information sharing, and cooperation across business functions. As a consequence, the walls that separate stages and functions of work tend to come down, and the organization operates more in a team-oriented manner.

W. Edwards Deming was one of the founders of the quality management movement. His "14 points" of quality emphasized a holistic approach to management that demands intimate understanding of the process---the delicate interaction of materials, machines, and people that determine productivity, quality, and competitive advantage:

*SOURCE: MANAGEMENT: THE NEW COMPETITIVE LANDSCAPE, 6TH ED., 2004, THOMAS S. BATEMAN & SCOTT A. SNELL, PGS. 279-280*

end

|

Saturday, November 16, 2019

Managing for Competitive Advantage (part 10)

New Ventures (part D)

by

Charles Lamson

Intrapreneurship

Today's large corporations are more than passive bystanders in the entrepreneurial explosion. Even established companies try to find and pursue new and profitable ideas---and they need intrapreneurs to do so. If you work in a company, and are considering preparing a new business venture, table one can help you decide whether the new idea is worth pursuing.

| ||||||||

TABLE 1 Checklist for Choosing Ideas

Building Support for Your Idea

A manager who has a new idea to capitalize on a market opportunity will need to get others in the organization to buy in or sign on. In other words, you need to build a network of allies who support and will help implement the idea.

If you need to build support for a project idea, the first step involves clearing the investment with your immediate boss or boss's. At this stage, you explain the idea and seek approval to look for wider support.

Higher executives often want evidence that the project is backed by your peers before committing to it. This involves making cheerleaders---people who will support the manager before formal approval from higher levels. Some managers refer to this strategy as "loading the gun"---lining up ammunition in support of your idea.

Next, horse trading begins. You can offer Promises of payoffs from the project in return for support, time, money, and other resources that peers and others contribute.

Finally, you should get the blessing of relevant higher-level officials. This usually involves a formal presentation. You will need to guarantee the project's technical and political feasibility. Higher management endorsement of the project and promises of resources help convert potential supporters into an enthusiastic team. At this point, you can go back to your boss and make specific plans for going ahead with the project.

Along the way, expect resistance and frustration and use passion and persistence, as well as business logic, to persuade others to get on board.

Building Intrapreneurship

Two common approaches used to stimulate intrapreneurial activity are skunkworks and bootlegging. Skunkworks are project teams designed to produce a new product. A team is formed with a specific goal within a specified time frame. A respected person is chosen to be manager of the Skunkworks. In this approach to corporate innovation, risk takers are not punished for taking risks and failing---their former jobs are held for them. The risk takers also have the opportunity to earn large rewards.

Bootlegging refers to informal efforts by managers and employees to create new products and new processes. "Informal" can mean "secretive," such as when a bootlegger believes the company will frown on those activities. But the intrapreneurial organization should tolerate and even encourage bootlegging.

Organizing New Corporate Ventures

For large-scale innovation, strategic alliances---cooperation among different organizations---can be a useful route.

Hazards in Intrapreneurship

Organizations that encourage intrapreneurship face an obvious risk: the effort can fail. One author noted, “There is considerable history of internal venture development by large firms, and it does not encourage optimism. However, this risk can be managed. In fact, failing to foster intrapreneurship may represent a subtler but greater risk then encouraging it. The organization that resists intrapreneurial initiative may lose its ability to adapt when conditions dictate change.

The most dangerous risk in intrapreneurship is the risk of over-reliance on a single project. Many companies fail while awaiting the completion of one large, innovative project. The successful intrapreneurial organization avoids over-commitment to a single product and relies on its entrepreneurial spirit to produce at least one winner from among several projects.

Organizations also court failure when they spread their intrapreneurial efforts over too many projects. If there are many intrapersonal projects, each effort may be too small in scale. Managers will consider the project unattractive because of their small size. Or, those recruited to manage the projects may have difficulty building power and status within the organization.

The hazards in intrapreneurship, then, are related to scale. One large project is a threat, as are too many underfunded projects. But a carefully managed approach to this strategically important process will upgrade an organizations chances for long-term survival and success.

Entrepreneurial Orientation

In an earlier post, the characteristics of individual entrepreneurs were described. Now we do the same for companies we describe how companies: We describe how companies that are highly entrepreneurial differ from those that are not.

Entrepreneurial Orientation is the tendency of an organization to engage in activities designed to identify and capitalize successfully on opportunities to launch new ventures by entering new or established markets with new or existing goods or services. Entrepreneurial orientation is determined by five tendencies: to allow independent action, innovative, take risks, be proactive, and be completely aggressive.

To allow independent action is to grant to individuals and teams the freedom to exercise their creativity, champion promising ideas, and carry them through to completion. Innovativeness requires the firm to support new ideas, experimentation, and the creative processes that can lead to new products or processes; it requires a willingness to depart from existing practices and venture beyond the status quo. Risk-taking comes from a willingness to commit significant resources, and perhaps borrow heavily, to venture into the unknown. The tendency to take risks can be assessed by considering whether people are bold or cautious, whether they require high levels of certainty before taking or allowing action, and whether they tend to follow tried and true. paths.

To be proactive is to act in anticipation of future problems and opportunities. A proactive firm shapes the environment and changes the competitive landscape; other firms merely react. Proactive firms are forward-thinking and fast to act, and are leaders rather than followers. Similarly, some individuals are more likely to be proactive, to shape and create their own environments, than others who more passively cope with the situations in which they find themselves. Proactive firms encourage and allow individuals and teams to be proactive.

Finally, competitive aggressiveness is the tendency of the firm to challenge competitors directly and intensely in order to achieve entry or improve its position. In other words, it is a competitive tendency to outperform ones rivals in the marketplace. This might take the form of striking fast to beat competitors to the punch, to tackle them head-to-head, and to analyze and target competitors weaknesses.

What makes a firm "entrepreneurial" is its engagement in an effective combination of independent action, innovativeness, risk-taking, proactiveness, and competitive aggressiveness. The relationship between these factors and the performance of the firm is a complicated one that depends on many things. Nevertheless you can imagine how the opposite profile---too many constraints on action, business as usual, extreme caution, passivity, and a lack of competitive fire will undermine entrepreneurial activities. And without entrepreneurship, how would firms survive and thrive in a constantly changing competitive environment?

*SOURCE: MANAGEMENT: THE NEW COMPETITIVE LANDSCAPE, 6TH ED., 2004, THOMAS S. BATEMAN, SCOTT A. SNELL, PGS. 228-231*

end

|

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

What is my experience of the relationship between adoration and the Mass?

Key Points The relationship between Eucharistic adoration and the Mass is deeply interconnected, with adoration often enhancing the experien...

-

INTRODUCING CHANGE by Charles Lamson What elements influence others to buy into an idea or product? Researchers and practitioners ask t...

-

1 Peter 2:24 : "He himself bore our sins in his body on the cross, so that we might die to sins and live for righteousness; 'by hi...