That's what hip-hop is: It's sociology and English put to a beat, you know.

Inequalities of Social Class (Part B)

by

Charles Lamson

The Upper Classes

Sociologists regard the upper class as divided roughly into two subgroups: the richest and most prestigious families, who constitute the elite or "high society" and tend to be white Anglo-Saxon Protestants, and the "newly rich" families, who may be extremely wealthy but have not attained sufficient prestige to be included in the communities and associations of high society.

|

| FIGURE 1 Oil Tycoon John D. Rockefeller

At the beginning of the twentieth century, families whose wealth came from railroads and banking looked down on "upstarts" like Rockefeller (Figure 1) and Ford, whose money came from oil and automobiles. More recently, the great manufacturing families---the du Ponts (chemicals), the Rockefellers (oil), the Carnegies and Mellons (steel and coal)---have questioned the upper-class status of families like the Kennedys, whose wealth originally came from merchandising and whose Irish descent marked them off from the rich Protestant families.

Throughout much of the 20th century the number of family-owned fortunes declined as large corporations like General Motors, Boeing, and IBM gained greater economic power. But, the major family fortunes still represent billions of dollars of capital controlled by the members of immensely wealthy families, many of whom are not descended from earlier Yankee families. Other family names, such as Bill Gates of Microsoft or Michael Dell of Dell computers or even Oprah Winfrey, certainly one of the best-known and richest women in the United States, do not appear on the list because this compilation of family fortunes includes only those that have been active for more than one generation (Hacker, 1997, Money: Who Has How Much and Why).

Members of the upper class tend to create special places in which to live and relax (see Figure 3). They often maintain apartments in exclusive city neighborhoods and country estates in secluded communities. They send their children to the most expensive private schools and universities, maintain memberships in the most exclusive social clubs, and fly throughout the world to leisure resorts frequented by members of their own class (see Figure 4). Examples of these resorts and enclaves of great wealth include Vail and Aspen in Colorado, Palm Springs in California, Palm Beach in Florida, and large stretches of the New England coastline.

FIGURE 3 A Concern of the Elite

/GettyImages-1092630192-56b4a20e1ef14f888174097dd279766d.jpg)

FIGURE 4 Problem Solved

A question that sociologists continually debate is whether the upper class in America is also the society's ruling class. The question of whether great wealth also confers the ability to rule by controlling political actors (e.g., influence peddling) is open to empirical research and debate. Elite theorists like C. Wright Mills and William Domhoff argue that the upper class not only holds the controlling share of wealth and prestige, which it can pass along to its children, but also maintains a virtual monopoly over power in the United States (Zweigenhaft & Domhoff, 1998, Diversity in the Power Elite). A ruling class, Domhoff states, "is socially cohesive, has its basis in the large corporations and banks, plays a major role in shaping the social and political climate, and dominates the federal government through a variety of organizations and methods" (1983, p.1, Who rules America now?). Mills (1956, The Power Elite) attempted to show that this ruling class produces a power elite composed of its most politically active members plus high-level employees in the government and the military. The power elite, these sociologists claim, is the leadership arm of the ruling class.

Other sociologists and political scientists contend that there is no single, cohesive ruling class with an identifiable power elite that carries out its bidding. This is known as the pluralist concept (Polsby, 1980, Community Power and Political Theory; Sullivan, 1998, November-December. Defining Democracy Down. American Prospect, pp. 91-96). These researchers agree that there is a readily identifiable upper class in American society. However, its power is not exerted in a unified fashion because there are competing centers of wealth and power within the upper class; moreover, its members' viewpoints on social policy are often opposed to one another we return to the debate between the power elite and pluralist theories in a later part of this analysis.

FIGURE 5 Typical American Middle-Class Family

The Middle Classes

Unlike the upper classes in which family status establishes who is included in the highest stratum and who is not, the middle class includes far more varied combinations of wealth and prestige. While the concept is typically ambiguous in popular opinion in common language use (Dante Chinni, [May 10, 2005]. One more Social Security quibble: Who is middle class? The Christian Science Monitor), contemporary social scientists have put forth several congruent theories on the American middle class. Depending on the class model used, the middle class constitutes anywhere from 25% to 66% of households (Wikipedia).

One of the first major studies of the middle class in America was White Collar: The American Middle Classes, published in 1951 by sociologist C. Wright Mills. Later sociologists such as Dennis Gilbert of Hamilton College commonly divided the middle class into two subgroups. Constituting roughly 15% to 20% of households is the upper or professional middle class consisting of highly educated, salaried professionals and managers. Constituting roughly one-third of households is the lower-middle-class consisting mostly of semi-professionals, skilled craftsmen and lower level of management. (William Thompson and Joseph Hickey 2005. Society in Focus; Brian Williams, et al., 2005. Marriages, Families and Intimate Relationships).

So this large proportion of Americans who identify themselves as members of the middle class is by no means a homogeneous population. The middle class is often referred to as the middle classes to emphasize the existence of strata with differing income, education, and access to wealth. One group of Americans who identify themselves as members of the middle class are highly educated professionals (mentioned above). Most often they have attended graduate schools and built successful careers as engineers, lawyers, doctors, dentists, stockbrokers, or corporate managers. But their comfortable incomes, often much more than $100,000 a year, may also be derived from family-owned businesses. Members of this class typically live in the suburbs (see Figure 6).

FIGURE 6 The Suburbs

Another segment of the middle class is composed of people whose income is derived from small businesses, especially stores and community-oriented enterprises in contrast with large corporations that have offices at many locations. Often referred to as the petit bourgeoisie or independent small business owners, the members of this class may be found among the leaders of local chambers of commerce and other business associations that advocate local economic growth (Erik Olin Wright, et al., 1982, The American Class Structure. American Sociological Review, 47, 702-726; Wright, 1997, Class Counts).

The American concept of the middle class is based far more on patterns of consumption and the American dream of shared affluence than on the kinds of economic realities that Marx used to describe social classes. Americans have always believed that they could achieve individual affluence and become part of a great middle class. Thus in subjective terms the middle class is the largest single class in American society, but in cultural terms it is highly diverse because so many different lifestyles are represented within it.

The dominant image of the middle class from the end of World War II until the mid-1970s was of a Suburban population living in relatively new private homes (Scott, 1998. The United States of Suburbia). The culture of the suburban middle class was thought to be shaped by the experience of frequent changes of residence and long-distance commuting, together with status symbols like the "ranch house with its two-car garage, lawn & BBQ, and the nearby church and shopping center" (Schwartz, 1976, Images of Suburbia. In B. Schwartz, Ed., The Changing Face of the Suberbs, p. 327). The suburban middle class was said to be oriented toward family life and suspicious of the offbeat (Fava, 1956; Riesman, 1957, The Suburban Dislocation. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 314, 123-146). However, empirical research by several archaeologists, including Bennett Berger (1961, The Myth of Suburbia. Journal of Social Issues, 17, pp. 38-48), Herbert Gans (1967, 1976. The Uses of Poverty. In W. Feigelman, Ed., Sociology Full Circle, 4th ed.), and M. P. Baumgartner (1988, The Moral Order of a Suberb) has shown that suburban communities are far from homogeneous, that many people who think of themselves as members of the working class can be found in them, and that there is no easily identified middle-class suburban culture.

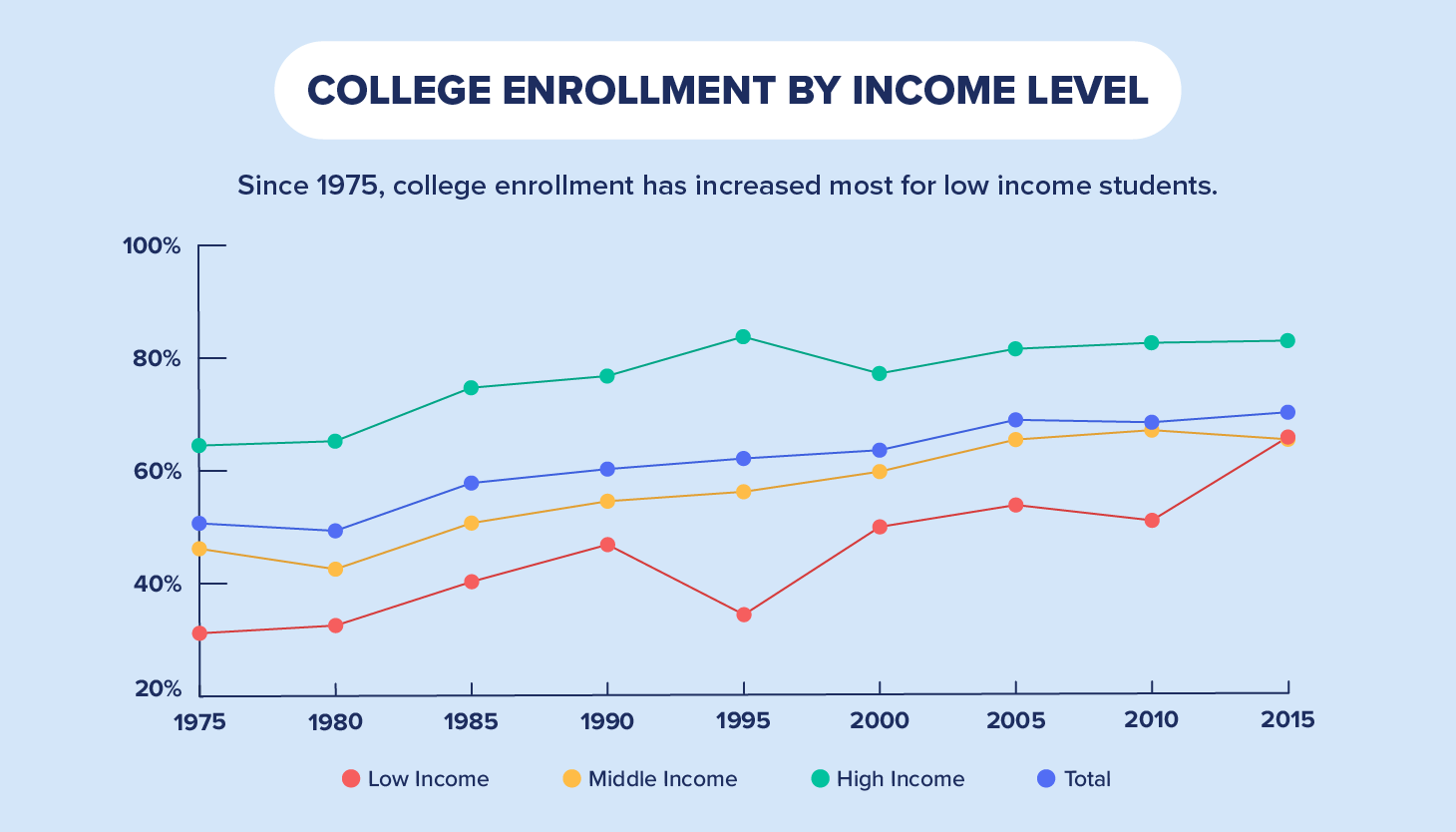

Another change in the nature of the middle class has to do with education. In the 1950s and 1960s a college diploma was often viewed as a passport to the American middle class way of life. But we will see later that, although education remains the primary route to upward mobility for people without inherited wealth, the college diploma has lost some of its power to open the door to middle-class prestige. Despite this, based on U.S. student loan debt statistics from 2015, since 1975, low-income college enrollment has had a sharp increase whereas high income (or upper-class) has appeared to level off since 2010.

FIGURE 7 (Natalie Issa, June 19, 2019, U.S. Student Loan Debt Statistics in 2019. Credit.com)

The most general points that sociologists can make about the middle class are that its members tend to be employed in non-manual occupations and that they usually have to work hard to afford the material things that are more easily acquired by the upper-middle class. Identification with the middle class is likely to be highest among teachers, middle and lower level office managers and clerical employees, government bureaucrats, and workers in the uniformed services.

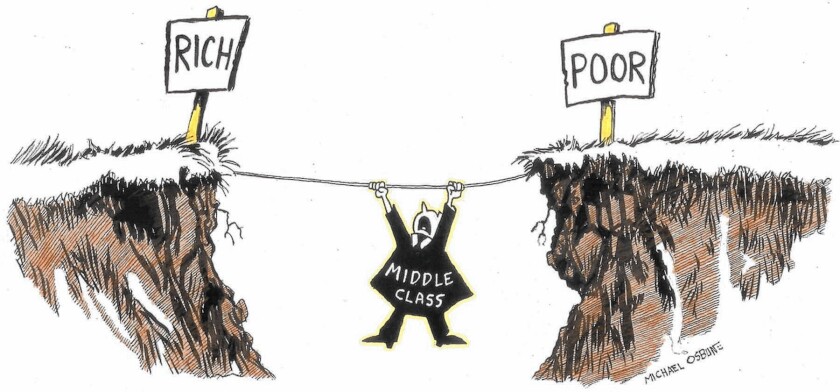

Effects of Economic Insecurity Political candidates attempt to win the support of the middle class because they recognize that large numbers of voters think of themselves as members of that class, rather than as rich or poor. But as we have seen, the idea of an all-inclusive American middle class is more of a myth than a reality for increasing numbers of working Americans. Between the extremes of poverty and wealth are, instead of a unified middle class, two increasingly distinct groups that think of themselves as middle class but face far different life chances and economic realities.

In the more secure segment of the middle class are highly skilled, highly educated professionals and managerial women and men who are doing rather well, although they increasingly experience income stagnation and must find ways to supplement their incomes. But below this segment there is a larger stratum of less-skilled and less-educated people who are experiencing ever greater economic insecurity resulting from stagnant incomes and declining living standards (see Figure 8). Appealing to this growing insecure middle-class stratum is a central goal of political leaders.

*MAIN SOURCE: SOCIOLOGY IN A CHANGING WORLD, 6TH ED., 2003, WILLIAM KORNBLUM, PP. 355-358*

end

|

No comments:

Post a Comment