Stratification and Global Inequality (Part D)

by

by

Charles Lamson

The French Revolution: A Case Study of Power, Authority, and Stratification

Max Weber defined power as "the probability that one actor within a social relationship will be in a position to carry out his own will despite resistance" (1947, The Theory of Social and Economic Organization, p. 152). This is a very general definition; it applies equally to a mugger with a gun and to an executive vice president ordering a secretary to get coffee for a visitor. But there is a big difference between the types of power used in these examples. In the first, illegitimate power is asserted through physical coercion. In the second, the secretary may not want to obey the vice president's orders yet recognizes that they are legitimate; that is, such orders are understood by everyone in the company to be within the vice president's power. This kind of power is called authority.

|

| FIGURE 1 The French Revolution

Even when power has been translated into authority, there remains the question of how authority originates and is maintained. This is a basic question in the study of stratification. As we saw in the last post, the fact that people in lower strata accept their place in society requires that we examine not only the processes of socialization but also how power and authority are used to maintain existing relations among castes or classes.

A brief review of the causes of the French Revolution of 1789 (see Figure 1) provides a case study in the relationship between power and authority on one hand and stratification on the other. Why did the French people accept the rule of absolute monarchs for so long before they finally ended that rule in a bloody revolution? In answering this question we can apply all the aspects of stratification discussed so far in previous posts. We will begin with the feudal stratification system.

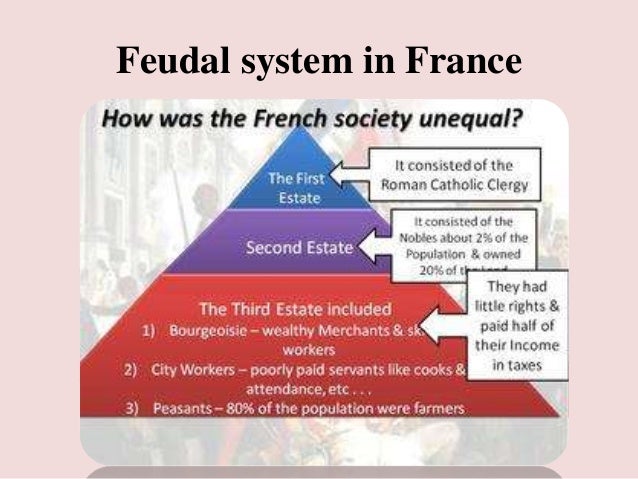

FIGURE 2 The Major Strata of Prerevolutionary French Society The major strata of French society (see Figure 2), called estates, were the nobility, the clergy, the peasantry, and the bourgeoisie (merchants, shopkeepers, and artisans). Each estate had its own institutions and culture, causing its members to feel that they were part of a unified community with its own norms and values. The estates were linked together by the time-honored norms of feudalism: vassalage and fealty. A vassal was someone who received the grants of land from a lord. In return He swore fealty, an oath of service and loyalty, to that lord. The lord, in turn swore fealty to a more powerful lord, until one reached the highest level of society, the king. In such a well-ordered and legitimate system where were the seeds of revolution? The answer lies in how power, authority, and changing modes of production combined to shake the foundations of feudal France.

In any system of stratification there are likely to be conflicts. These conflicts may be caused by the ambitions of a particular leader or group, but sometimes the characteristics of the system---and especially of the way its powerful members trying to cope with change create conflict. Both types of conflict existed in prerevolutionary France. In order to compete with the other major European powers, the king had to raise armies and send fleets abroad, both of which cost huge sums of money and required thousands of men. But the vow of fealty extended only from the king to the highest level of the nobility. The nobles, in turn, were responsible for seeing that their vassals provided more money and men. This system placed severe constraints on the king, who could not easily make direct payments on all his subjects. The king was dependent on the nobles and, through them, on the lesser lords. In return, the lesser lords often demanded more power, there by challenging the king's authority. In order to reduce the power of the lords, the king (see Figure 3) went to the clergy and the bourgeoisie for assistance.

FIGURE 3 Louis XVI: The King During the French Revolution

As the cities grew and the trading and manufacturing capacities of the bourgeoisie expanded, the king was increasingly successful at drawing on the wealth of the bourgeoisie and undermining the power of the feudal lords. The court flourished in fact. it seemed that the king's power had become absolute. But beneath the pomp and display of the court the feudal stratification system was in ruins. The weakened nobility could no longer hold the fealty of the peasants. Throughout the countryside The peasants groaned under the heavy debts imposed by their feudal masters, and they began to question the right of the nobility to tax them.

Meanwhile, in the cities and towns the rapidly growing bourgeoisie, along with the new social stratum of urban workers, clearly understood that the king's power derived from their productive activities. They felt that they were not adequately rewarded for their support. At the same time, another new stratum, the intellectuals---people who had been educated outside the church and the court---was creating a new ideology and promoting it through new institutions like the press. This new ideology---"liberty, equality, fraternity"---helped spur revolutionary social movements, but the underlying cause of the revolution was a drastic change in the stratification system, in which the new middle class of wealthy business owners (the bourgeoisie) eventually challenged the ancient aristocracy.

*MAIN SOURCE: SOCIOLOGY IN A CHANGING WORLD, 6TH ED., 2003, WILLIAM KORNBLUM, P. 318-319*

end

|

No comments:

Post a Comment