One of the key places where sociology should be used is in analyzing 'the world' of our times, so that we can be more discerning. To resist the dangers of the world, you have to recognize the distortions and seductions of the world.

Population and Environment in an Urbanizing World (Part B)

by

Charles Lamson

by

Charles Lamson

The Urban Landscape

Urban Expansion

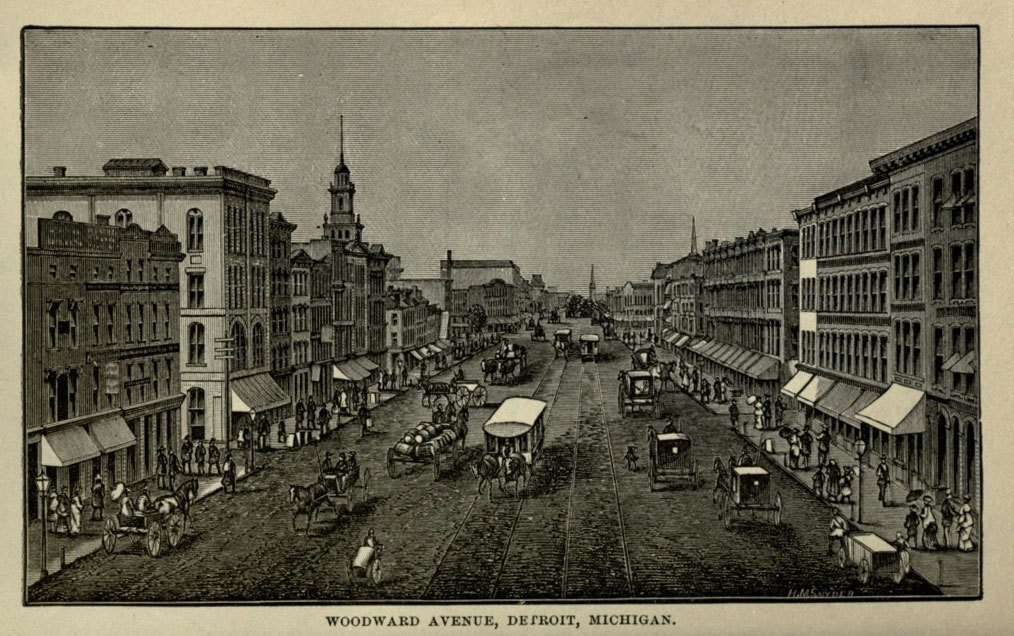

The effects of urbanization began to be felt in American society in the mid-19th century. As growing numbers of people settled in the West, waves of immigrants from Ireland, Germany, Italy and many other parts of southern and central Europe streamed into the cities of the East. In the 1840s and the 1850s, for example, approximately 1.35 million Irish immigrants arrived in the United States, and in just 12 years, from 1880 to 1892, more than 1.7 million Germans arrived (Bogue, 1983, The Population of the United States). In future posts I have more to say about the impact from the migrations from China, Korea, and Latin America, the importation of slaves from Africa, and the large number of people of all races and ethnic groups who continue to arrive in U.S. cities. The point here is that for 150 years, North American cities have been a preferred destination of people from all over the world, as a result, they have received numerous waves of newcomers since their period of explosive growth in the 19th century (see Figure 1).

|

FIGURE 1 Circa Late 19th Century

The science of sociology found early supporters in the United States and Canada partly because the cities in those nations were growing so rapidly. It often appeared that North American cities would be unable to absorb all the newcomers who were arriving in such large numbers. Presociological thinkers like Frederick Law Olmsted, the founder of the movement to build parks and recreation areas in cities, and Jacob Riis, an advocate of slum reform, urged the nation's leaders to invest in improving the urban environment, building parks and beaches, and making better housing available to all (Cranz 1982, The Politics of Park Design; Kornblum & Lawler, 1999, Handbook of Park User Research). These reform efforts were greatly aided by sociologists who conducted empirical research on the social conditions in cities. In the early 20th century many sociologists lived in cities like Chicago that were characterized by rapid population growth and serious social problems. It seemed logical to use empirical research to construct theories about how cities grow and change in response to major social forces as well as more controlled urban planning.

The founders of the Chicago school of sociology, Robert Park and Ernest Burgess, attempted to develop a dynamic model of the city, one that would account not only for the expansion in cities in terms of population and territory but also for the patterns of settlement and use within cities. They identifies several factors that influence the physical form of cities. Among them are "transportation and communication, tramways and telephones, newspapers and advertising, steel construction and elevators---all thing in fact which tend to bring about a greater mobility and a greater concentration of the urban populations" (Park, 1967/1925a, The City. In R. E Park & Burgess, Eds., The City, p. 2). The important role of transportation is described in one of Park's essays:

The extent to which . . . an increase of population in one part of the city is reflected in every other depends very largely upon the character of the local transportation system. Every extension and multiplication of the means of transportation connecting the periphery of the city with the center tends to bring more people to the central business district, and to bring them there oftener. This increases the congestion in the center; it increases, eventually, the height of office buildings and the values of the land on which those buildings stand. The influence of land values at the business center radiates from that point to every part of the city. (1967/1926, pp. 57-58)

The Concentric-Zone Model Park and Burgess based their model of urban growth on the concept of natural areas---that is, areas in which the population is relatively homogeneous and land is used in similar ways without deliberate planning. In Park's words:

Every great city has its racial colonies, like the Chinatowns of San Francisco and New York, the Little Sicily of Chicago. . . . Most cities have their segregated vice districts . . . their rendezvous for criminals and various sorts. Every large city has its occupational suberbs like the Stockyards in Chicago, and its residential enclaves, like Brookline in Boston. (1967/1925a, p. 10)

Park and Burgess saw urban expansion as occurring through a series of "invasions" of successive zones or areas surrounding the center of the city. For example, migrants from rural areas and other societies "invaded" areas where the housing was cheap. Those areas tended to be close to the places where they worked. In turn, people who could afford better housing and the cost of commuting "invaded" areas further from the business district, and these became the Brooklines, Gold Coasts, and the Greenwich Villages of their respective cities. Park and Burgess's Model, which has come to be known as the concentric-zone model, is portrayed in Figure 2. Because the model was originally based on studies of Chicago, its center is labeled "Loop," the term that is commonly applied to that city's central commercial zone. Surrounding the central zone is a "zone in transition," an area that is being invaded by business and light manufacturing. The third zone is inhabited by workers who do not want to live in the factory or business district but at the same time need to live reasonably close to where they work. The fourth, or residential, zone consists of higher class apartment buildings and single-family homes. And the outermost ring, outside the city limits, is the suburban or commuters' zone; its residents live within a 30- to 60-minute ride of the central business district (Burgess,1925, The Growth of the City, In Burgess & Park, Eds., The City).

Studies by Park, Burgess, and other Chicago school sociologists showed how new groups of immigrants tended to become concentrated in segregated areas within inner-city zones, where they encountered suspicion, discrimination, and hostility from ethnic groups that had arrived earlier. Over time, however, each group was able to adjust to life in the city and to find a place for itself in the urban economy. Eventually many of the immigrants were assimilated into the institutions of American society and moved to desegregated areas in outer zones; the ghettos they left behind were promptly occupied by new waves of immigrants.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/55406995/suburbs.0.jpg)

Note that each zone is continually expanding outward. Thus, Burgess wrote, "If this chart is applied to Chicago, all four of these zones were in its early history included in the circumference of the inner zone, the present business district. The present boundaries of the [zone in transition] were not many years ago those of the zone now inhabited by independent wage-earners" (1925, p. 50). Burgess also pointed out that "neither Chicago nor any other city fits perfectly into this [model]. Complications are introduced by the lake front, the Chicago River, railroad lines, historical factors in the location of industry, the relative degree of the resistance of communities to invasion, etc." (pp. 50-51).

The Park and Burgess model of growth in zones and natural areas of the city can still be used to describe patterns of growth in cities that were built around a central business district and continue to attract large numbers of immigrants. But this model is biased toward the commercial and industrial cities of North America, which have tended to form around business centers rather than around palaces or cathedrals as is the case in so many other parts of the world. Moreover it fails to account for other patterns of urbanization, such as the rise of satellite cities and the rapid urbanization that occurs along commercial transportation corridors.

*MAIN SOURCE: SOCIOLOGY IN A CHANGING WORLD, 6TH ED., 2003, WILLIAM KORNBLUM, PP. 254-256*

end

|

No comments:

Post a Comment