Marketing, Planning and Implementation

(part A)

by

Charles Lamson

Introduction

Marketing does not just happen. Products and services have to be developed in the most efficient manner to ensure that the goods or services reach the consumer in the right manner at the right place, time and price to create customer satisfaction and appropriate profit to the supplier. It is the planning required throughout the marketing process that will be discussed in the next few posts.

The Nature of Planning

While it may be tempting for a young entrepreneur to rush off to market his/her new product or service, very soon hurdles will be encountered for which he/she is not prepared. The good idea will be unlikely to be successfully implemented, causing considerable loss of face, time and money through the venture. Although frustrating, it is better to sit down and plan out the process of getting the offering to market. However, good planning takes time and careful consideration to implement. Even established marketers who have products at various stages of the product life cycle (PLC) find marketing planning challenging. Various academics have written useful texts which will provide further guidance to the process of developing and implementing effective marketing plans. The reader is referred to the work of McDonald (2002) and Cooper and Payne (1996) who extend the coverage to services marketing.

Business Plan

The business plan is central to the planning process, often being the critical document that is needed to persuade others to support the venture. Business plans form a framework which outline the route to reach the business goals. Usually business plans are made to cover a period of up to three, maybe even five years. Generally the detail is provided for year 1 of the operation, with more indicative expectations thereafter for years 2 and 3. Many business plans are prepared as part of the process of getting financing in the form of venture capital or loans from a bank or equivalent institution. The firm's management will require the plan to ascertain that the proposals have been well considered and that projections of likely performance match expectations. The business plan will incorporate details of the proposed marketing plan (see Box 1) showing the direction that the marketing mix is expected to take. It will give estimates of customer demand in terms of market size, competitor activity, projected profit and loss together with the time scale, human resource and financial implications estimates. Supporting evidence in the form of test marketing findings may also be provided in the plan.

Generally, while the business plan is taken as the 'blueprint' for the venture to follow, it should not be a document that is written on tablets of stone. Time spent at this early stage can avoid costly mistakes as the plan is put into practice. However, ultimately, the plan acts as a guide which may have to be adjusted and revised over time to match the market conditions faced in its implementation. The business plan is a tool to help manage the venture through the various stages of its development.

BOX 1

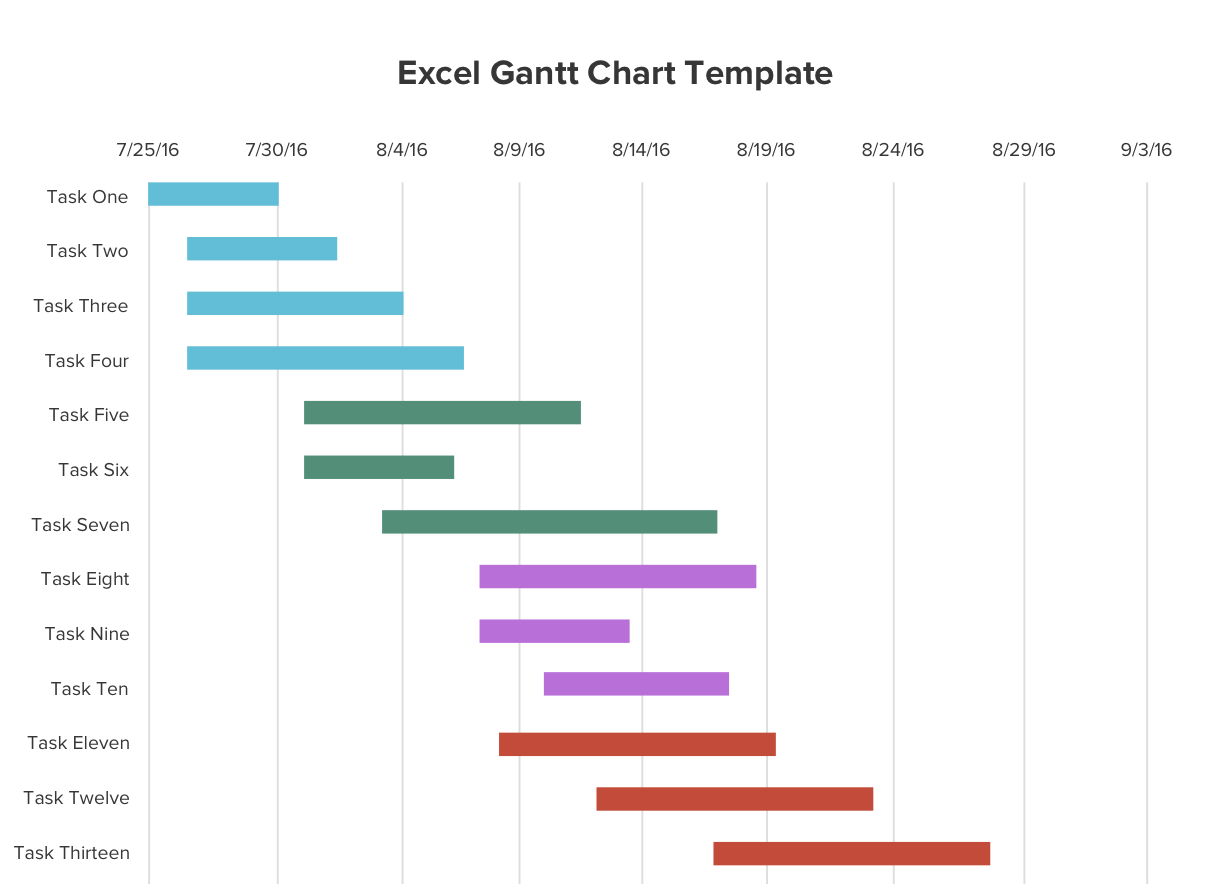

Figure 1 An example of a Gantt chart used in marketing planning

*SOURCE: FUNDAMENTALS OF MARKETING, 2007, MARILYN A. STONE AND JOHN DRESMOND, PGS. 395-399*

END

|