The Evolution of Management

by

Charles Lamson

For thousands of years, managers have wrestled with the same issues and problems confronting executives today. Around 1100 B.C., the Chinese practiced the four management functions---planning (specifying the goals to be achieved and deciding in advance the appropriate actions needed to achieve those goals), organizing (assembling and coordinating the human, financial, physical, informational, and other resources needed to achieve goals), leading (stimulating people to be high performers), and controlling (monitoring progress and implementing necessary changes). Between 350 and 400 BC, the Greeks recognized management as a separate art and advocated a scientific approach to work. The Romans decentralized the management of their vast empire before the birth of Christ. During medieval times, the Venetians standardized production through the use of an assembly line, building warehouses and using an inventory system to monitor the contents.

|

But throughout history most managers operated strictly on a trial-and-error basis. The challenges of the industrial revolution changed that. Management emerged as a formal discipline at the turn of the century. The first university programs to offer management and business education, the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania and the Amos Tuck School at Dartmouth, were founded in the late 19th century. By 1914, 25 Business schools existed.

Thus, the management profession as we know it today is relatively new. This post explores the roots of modern management theory. Understanding the origins of management thought will help you grasp the underlying contexts of the all the ideas and concepts presented in the posts ahead.

Although this post is titled "The Evolution of Management," it might be more appropriately called "The Revolutions of Management," because it documents the wide swings in management approaches over the last 100 years. Out of the great variety of ideas about how to improve management, parts of each approach have survived and been incorporated into modern perspectives on management. Thus, the legacy of past efforts, triumph, and failures has become our guide to future management practice.

Early Management Concepts and Influences

Communication and transportation constraints hindered the growth of earlier businesses. Therefore, improvements in management techniques did not substantially improve performance. However, the industrial revolution changed that. As companies grew and became more complex, minor improvements in management tactics produced impressive increases in production quantity and quality.

The emergence of economies of scale---reductions in the average cost of a unit of production as the total volume produced increases---drove managers to strive for further growth. The opportunities for mass production created by the industrial revolution spawned intense and systematic thought about management problems and issues---particularly efficiency, production processes, and cost savings.

This post depicts the evolution of management through the mid-to-late 19th, 20th, and early 21st centuries. This historical perspective is divided into two major sections: classical approaches and contemporary approaches. Many of these approaches developed simultaneously, and they often had a significant impact on one another. Some approaches were a direct reaction to the perceived deficiencies of previous approaches. Others developed as the needs and issues confronting managers changed over the years. All the approaches attempted to explain the real issues facing managers and provide them with tools to solve future problems.

Classical Approaches

The classical period extended from the mid-nineteenth century through the early 1950s. The major approaches that emerged during this. Were systematic management, scientific management, administrative management, human relations, and bureaucracy.

Systematic Management During the 19th century, growth in U.S. business centered on manufacturing. Early writers such as Adam Smith believed the management of these firms was chaotic, and their ideas helped to systematize it. Most organizational tasks are subdivided and performed by specialized labor. However, poor coordination among subordinates and different levels of management cause frequent problems and breakdowns of the manufacturing process.

The systematic management approach attempted to build specific procedures and processes into operations to ensure coordination of effort. Systematic management emphasized economical operations, adequate staffing, maintenance of inventories to meet consumer demands, and organizational control. These goals were activated through

Systematic management emphasized internal operations because managers were concerned primarily with meeting the explosive growth in demand brought about by the industrial revolution. In addition, managers were free to focus on internal issues of efficiency, in part because the government did not constrain business practices significantly. Finally, labor was poorly organized. As a result, many managers were oriented more toward things than toward people.

Although systematic management did not address all the issues 19th century managers faced, it tried to raise managers' awareness about the most pressing concerns of their job.

Scientific Management Systematic management failed to lead to widespread production efficiency. The shortcoming became apparent to a young engineer named Frederick Taylor who was hired by Midvale Steel Company in 1878. Taylor discovered that production and pay were poor, inefficiency and waste were prevalent, and most companies had tremendous unused potential. He concluded that management decisions were unsystematic and that no research to determine the best means of production existed.

In response, Taylor introduced a second approach to management known as scientific management. This approach advocated the application of scientific methods to analyze work and to determine how to complete production tasks efficiently. For example, U.S. Steel's contract with the United Steelworkers of America specified that sand shovelers should move 12.5 shovelfuls per minute: shovelfuls should average 15 pounds of river sand composed of 5.5% moisture.

Taylor identified four principles of scientific management:

To implement this approach Taylor use techniques such as time and motion studies. With this technique, a task was divided into its basic movements, and different motions were timed to determine the most efficient way to complete the task.

After the one best way to perform the job was identified, Taylor stressed the importance of hiring and training the proper worker to do that job. Taylor advocated the standardization of tools, the use of instruction cards to help workers, and breaks to eliminate fatigue.

Another key element of Taylor's approach was the use of the differential piece-rate system. Taylor assumed workers were motivated by receiving money. Therefore, he implemented a pay system in which workers were paying additional wages when they exceeded a standard level of output for each job. Taylor concluded that both workers and management would benefit from such an approach.

Scientific management principles were widely embraced. Other properties, including other proponents, including Henry Gantt and Frank and Lillian Gilbreth, introduced many refinements and techniques for applying scientific management on the factory floor. One of the most famous examples of the application of scientific management is the factory Henry Ford built to produce the Model T.

At the turn of the century, automobiles were a luxury that only the wealthy could afford. They were assembled by craftspeople who put an entire car together at one spot on the factory floor. These workers were not specialized and Henry Ford believed they wasted time and energy bringing the needed parts to the car. Ford took a revolutionary approach to automobile manufacturing by using scientific management principles.

Administrative Management The administrative management approach emphasized the perspective of senior managers within the organization, and argued that management was a profession and could be taught.

An explicit and broad framework for administrative management emerged in 1916, when Henri Fayol, a French mining engineer and executive, published a book summarizing his management experiences. Fayol identified five functions and of management. The five functions, which are very similar to the four functions discussed in the opening paragraph of this post, include planning, organizing, commanding, coordinating, and controlling.

A host of other executives contributed to the administrative management literature. These writers discussed a broad spectrum of management topics, including the social responsibilities of management, the philosophy of management, clarification of business terms and concepts, and organizational principles. Chester Barnard's and Mary Parker Follet's contributions have become classic works in this area.

Barnard, former president of New Jersey Bell Telephone Company, published his landmark book The Function of the Executive in 1938. He outlined the role of the senior executive: formulating the purpose of the organization, hiring key individuals, and maintaining organizational communications. Mary Parker Follet's 1942 book Dynamic Organization extended Barnard's work by emphasizing that continually changing situations that managers face. Two of her key contributions---the notion that managers desire flexibility and the difference is between motivating groups and individuals---laid the groundwork for the modern contingency approach discussed later in this post.

All the writings in the administrative management area emphasized management as a profession along with fields such as law and medicine. In addition, these authors offered many recommendations based on their personal experiences, which often included managing large corporations. Although these perspectives and recommendations were considered sound, critics noted that they might not work in all settings. Different types of personnel, industry conditions, and technologies may affect the appropriateness of these principles.

Human Relations A fourth approach to management, human relations, developed during the 1930s. This approach aimed at understanding how psychological and social processes interact with the work situation to influence performance. Human relations was the first major approach to emphasize informal work relationships and worker satisfaction.

This approach owes much to other major schools of thought. For example, many of the ideas of the Gilbreths (scientific management) and Barnard and Fullet (administrative management) influenced the development of human relations from 1930 to 1955. In fact, human relations emerged from a research project that began as a scientific management study.

Western Electric Company, a manufacturer of communications equipment, hired a team of Harvard researchers led by Elton mayo and Fritz Roethlisberger. They were to investigate the influence of physical working conditions on worker productivity and efficiency in one of the company's factories outside Chicago. This research project known as the Hawthorne Studies, provided some of the most interesting and controversial results in the history of management.

The Hawthorne Studies were a series of experiments conducted from 1924 and 1932. During the first stage of the project (The Illumination Experiments), various working conditions, particularly the lighting in the factory were altered to determine the effects of those changes on productivity. The researchers found no systematic relationship between the factory lighting and production levels. In some cases, productivity continued to increase even when the illumination was reduced to the level of moonlight. The researchers concluded that the workers performed and reacted differently because the researchers were observing them. This reaction is known as the Hawthorne Effect.

This conclusion led the researchers to believe productivity may be affected more by psychological and social factors than by physical or objective influences. With this thought in mind, they initiated the other four stages of the project. During these stages, the researchers performed various work group experiments and had extensive interviews with employees. Mayo and his team eventually concluded that productivity and employee behavior or influenced by the informal work group.

Human relations proponents argued that managers should stress primarily employee welfare, motivation, and communication. They believed social needs had precedence over economic needs. Therefore, management must gain the cooperation of the group and promote job satisfaction and group norms consistent with the goals of the organization.

Another noted contributor to the field of human relations was Abraham Maslow. In 1943, Maslow suggested that humans have five levels of needs. The most basic needs are the physical needs for food, water, and shelter, the most advanced need is for self-actualization, or personal fulfillment. Maslow argued that people try to satisfy their lower-level needs and then progress upward to the highest level needs. Managers can facilitate this process and achieve organizational goals by removing obstacles and encouraging behaviors that satisfy people's needs and organizational goals simultaneously.

Although the human relations approach generated research into leadership, job attitudes, and group dynamics, it drew heavy criticism. Critics believed that one result of human relations---a belief that a happy worker was a productive worker---was too simplistic. While scientific management overemphasized the economic and formal aspects of the workplace, human relations ignored the more rational side of the worker and the important characteristics of the formal organization. However, human relations was a significant step in the development of management thought, because it prompted managers and researchers to consider the psychological and social factors that influence performance.

Bureaucracy Max Weber, a German sociologist, lawyer, and social historian, showed how management itself could be more efficient and consistent in his book The Theory of Social and Economic Organizations. The ideal model for management, according to Weber, is the bureaucracy approach.

Weber believed bureaucratic structures can eliminate the variability that results when managers in the same organization have different skills, experiences, and goals. Weber advocated that the jobs themselves be standardized so that personal changes would not disrupt the organization. He emphasized a structured, formal network of relationships among specialized positions in an organization. Rules and regulations standardized behavior, and authority resides in positions rather than in individuals. As a result, the organization need not rely on a particular individual, but will realize efficiency and success by following the rules in a routine and unbiased manner.

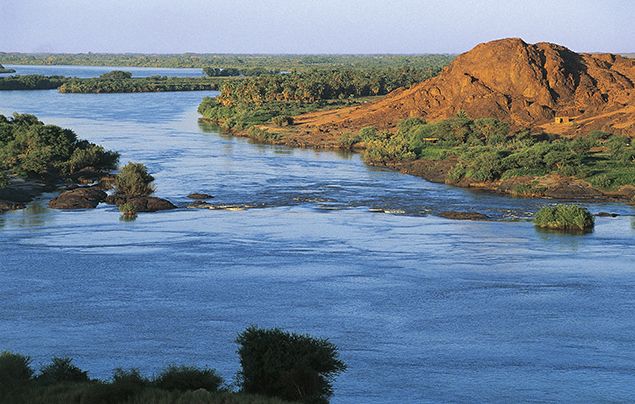

/GettyImages-96869652-f6700d0efa8c4efb8031043af8ccaf8e.jpg)

According to Weber, bureaucracies are especially important because they allow large organizations to perform the many routine activities necessary for their survival. Also, bureaucratic positions foster specialized skills, eliminating many subjective judgments by managers. In addition, if the rules and controls are established properly, bureaucracies should be unbiased in their treatment of people, both customers and employees.

Many organizations today are bureaucratic. Bureaucracy can be efficient and productive. However, bureaucracy is not the appropriate model for every organization. Organizations or departments that need rapid decision-making and flexibility may suffer under a bureaucratic approach. Some people may not perform their best with excessive bureaucratic rules and procedures.

Other shortcomings stem from a faulty execution of bureaucratic principles rather than from the approach itself. Too much authority may be vested in too few people, the procedure may become the ends rather than the means of managers or managers may ignore appropriate rules and regulations. Finally, one advantage of a bureaucracy---its permanence---can also be a problem. Once a bureaucracy is established, dismantling it is very difficult.

Contemporary Approaches

The Contemporary approaches to management include quantitative management, organizational behavior, systems theory, and the contingency perspective. Contemporary approaches have developed at various times since World War II, and they continue to represent the cornerstones of modern management thought.

Quantitative Management Although Taylor introduced the use of science as a management tool early in the twentieth century, most organizations did not adopt the use of quantitative techniques for management problems until the 1940s and 1950s. During World War II, military planners began to apply mathematical techniques to defense and logistic problems. After the war, private corporations began assembling teams of quantitative experts to tackle many of the complex issues confronting large organizations. This approach, referred to as quantitative management, emphasizes the application of quantitative analysis to management decisions and problems.

Quantitative management helps a manager make a decision by developing formal mathematical models of the problem. Computers have facilitated the development of specific quantitative methods. These include such techniques as statistical decision theory, linear programming, queuing theory, simulation, forecasting, inventory modeling, network modeling, and break-even analysis. Organizations apply these techniques in many areas, including production, quality control, marketing, human resources, finance, distribution, planning, and research and development.

Despite the promise quantitative management holds, managers do not rely on these methods as the primary approach to decision-making. Typically, they use these techniques as a supplement or tool in the decision process. Many managers will use results that are consistent with their experience, intuition, and judgment, but they will reject results that contradict their beliefs. Also, managers may use the process to compare alternatives and eliminate weaker options.

Several explanations account for the limited use of quantitative management. Many managers have not been trained in using these techniques. Also, many aspects of a management decision cannot be expressed through mathematical symbols and formulas. Finally, many of the decisions managers face are non-routine and unpredictable.

Organizational Behavior During the 1950's, a transition took place in the human relations approach. Scholars began to recognize that worker productivity and organizational success are based on more than the satisfaction of economic or social needs. The revised perspective known as organizational behavior, studies and identifies management activities that promote employee effectiveness through an understanding of the complex nature of individual, group, and organizational processes. Organizational behavior draws from a variety of disciplines including psychology and sociology to explain the behavior of people on the job.

During the 1960s, organizational behaviorists heavily influenced the field of management. Douglas McGregor's Theory X and Theory Y marked the transition from human relations. According to McGregor, Theory X managers assume workers are lazy and irresponsible and require constant supervision and external motivation to achieve organizational goals. Theory Y managers assume employees want to work and can direct and control themselves. McGregor advocated a Theory Y perspective, suggesting that managers who encourage participation and allow opportunities for individual challenge and initiative would achieve superior performance.

Other major organizational behaviorists include Chris Argyris, who recommended greater autonomy and better jobs for workers, and Rinsis Likert, who stressed the value of participative management. Through the years, organizational behavior has consistently emphasized development of the organization's human resources to achieve individual and organizational goals. Like other approaches, it has been criticized for its limited perspective, although more recent contributions have a broader and more situational viewpoint. In the past few years, many of the primary issues addressed by organizational behavior have experienced a rebirth with a greater interest in leadership, employee involvement, and self-management.

Systems Theory The classical approaches as a whole were criticized because they (1) ignored the relationship between the organization and its external environment, and (2) usually stressed what aspect of the organization or its employees at the expense of other considerations. In response to these criticisms, management scholars during the 1950's stepped back from the details of the organization to attempt to understand it as a whole system. These efforts were based on a general scientific approach called systems theory. An organization is a managed system that transforms inputs (raw materials, people, and other resources) into outputs (the goods and services that comprise its products).

Contingency Perspective Building on systems theory ideas, the contingency perspective refutes universal principles of management by stating that a variety of factors, both internal and external to the firm, may affect the organization's performance. Thus, there is no one best way to manage and organize, because circumstances vary. For example, a universal strategy of offering low-cost products would not succeed in a market that is not cost-conscious.

Situational characteristics are called contingencies. Understanding contingencies helps a manager know which set of circumstances dictate which management actions. You will learn the recommendations for the major contingencies throughout this analysis. The contingencies include:

With an eye to these contingencies, a manager may categorize the situation and then choose the proper competitive strategy, organization structure, or management process for the circumstances.

Researchers continue to identify key contingency variables and their effect on management issues. As you read the topics covered in each part of this analysis, you will notice the similarities and differences among management situations and the appropriate responses. This perspective should represent a cornerstone of your approach to management. Many of the things you will learn about throughout this analysis apply a contingency perspective.

Contemporary Approaches

All of these historical perspectives have left legacies that affect contemporary management thought and practice. There undercurrents continue to flow, even as the context and the specifics change.

But new approaches to management continue to appear and contribute to an ever-changing management profession. The remaining posts report on these dynamic, contemporary perspectives. For example, the 1980s brought a new gospel called quality management, new perspectives on competition and on business strategy, a focus on excellence, and a renewed interest in people, including both employees and customers. The 1990s brought theories and practices such as learning organization, lean manufacturing, knowledge management, and the characteristics of corporate cultures that helped to build great and enduring companies. The rest of this analysis, and perhaps the rest of your career, will be spent enacting the management functions, the drivers of competitive advantage, the enduring aspect of the historical perspectives, and the continually evolving contemporary perspectives on the successful practices of management.

*SOURCE: MANAGEMENT: THE NEW COMPETITIVE LANDSCAPE, 6TH ED., 2004, THOMAS S. BATEMAN & SCOTT A. SNELL, PGS. 30-37*

end

|

No comments:

Post a Comment