―

Externalities, Public Goods, Imperfect Information, and Social Choice

(Part B)

by

Charles Lamson

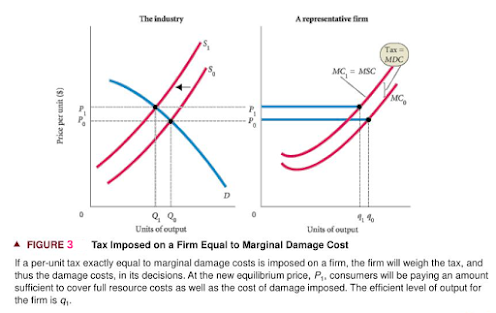

Private Choices and External Effects

To help us understand externalities, let us use a simple two person example. Harry lives in a dormitory at a big public college in the Southwest, where he is a first-year student. When he graduated from high school, his family gave him an expensive stereo system. Unfortunately, the walls of Harry's dorm are made of quarter-inch sheetrock over 3-inch aluminum studs. You can hear people sleeping four rooms away. Harry likes bluegrass music. Because of a hearing loss after an accident on the Fourth of July some years ago, he often does not notice the volume of his music. Jake, who lives next door to Harry is not much of a music lover, but when he does listen, it is to Brahms and occasionally Mozart. So Harry's music bothers Jake. Let us assume there are no further external costs or benefits to anyone other than Harry and Jake. Figure 2 diagrams the decision process that the to dorm residents face. The downward sloping curve labeled MB represents the value of the marginal benefits that Harry derives from listening to his music. Of course, Harry does not sit down to draw this curve, any more than anyone else (other than an economics student) set down to draw actual demand curves. Curves like this are simply abstract representations of the way people behave. If you think about it, such a curve must exist. To ask how much an hour of listening to music is worth to you is to ask how much you would be willing to pay to have it. Start at $0.01 and raise the "price" slowly in your mind. Presumably, you must stop at some point; where you stop depends on your taste for music and your income. You can think about the benefits Harry derives from listening to bluegrass as the maximum amount of money that he would be willing to pay to listen to his music for an hour. For the first hour, for instance, the figure for MB is $0.50. We assume diminishing marginal utility, of course. The more hours Harry listens, the lower the additional benefits from each successive hour. As the diagram shows, the MB curve falls below $0.05 per hour after 8 hours of listening. In the simple society of Jake and Harry, it is easy to add up social benefits and costs. At every level of output (stereo playing time), total social cost is the sum of the private costs borne by Harry and the damage costs borne by Jake. In Figure 2 MPC (constant at $0.05 per hour) is added to MDC to get MSC. Consider now what would happen if Harry simply ignored Jake. If Harry decides to play the stereo, Jake will be damaged. As long as Harry gains more in personal benefits from an additional hour of listening to music than he incurs in costs, the stereo will stay on. He will play it for 8 hours (the point where Harry's MB equals MPC). This result is inefficient; for every hour of play beyond 5, the marginal social cost borne by society---in this case, a society made up of Harry and Jake---exceeds the benefits to Harry---that is, MSC is greater than Harry's MB. It is generally true that when economic decisions ignore external costs, whether those costs are born by one person or by society, those decisions are likely to be inefficient. We will return to Harry and Jake to see how they deal with their problem. First, we need to discuss the general problem of correcting for externalities. Internalizing Externalities A number of mechanisms are available to provide decision-makers with incentives to weigh the external costs and benefits of their decisions, a process called internalization. In some cases, externalities are internalized through bargaining and negotiation without government involvement. In other cases, private bargains fail and the only alternative may be government action of some kind. Five approaches have been taken to solving the problem of externalities: (1) government-imposed taxes and subsidies, (2) private bargaining and negotiation, (3) legal rules and procedures, (4) sale or auctioning of rights to impose externalities, and (5) direct government regulation. While each is best suited for a different set of characteristics, all five provide decision makers with an incentive to weigh the external effects of their decisions. Taxes and Subsidies Traditionally, economists have advocated marginal taxes and subsidies as a direct way of forcing firms to consider external costs or benefits. When a firm imposes an external social cost, the reasoning goes, a per-unit tax should be imposed equal to the damages of each successive unit of output produced by the firm---the tax should be exactly equal to marginal damage costs. Because a profit-maximizing firm equates price with marginal cost, the new price to consumers covers both the resource costs of producing the product and the damage costs. The consumer decision process is once again efficient at the margin, because marginal social benefit as reflected in market price is equal to the full marginal cost of the product. Measuring Damages The biggest problem with this approach is that damages must be estimated in financial terms. For the detergent plant polluting the nearby river to be properly taxed, the government must evaluate the damages done to residents downstream in money terms. This is difficult, but not impossible. When legal remedies are pursued, judges are forced to make such estimates as they decide on compensation to be paid. Surveys of "willingness-to-pay,"studies of property values in affected versus nonaffected areas, and sometimes the market value of recreational activities can provide basic data. The monetary value of damages to health and loss of life is, actually, much more difficult to estimate, and any measurement of such losses is controversial. Even here, policymakers frequently make judgments that implicitly set values on life and health. Tens of thousands of deaths and millions of serious injuries result from traffic accidents in the United States every year, yet Americans are unwilling to give up driving or to reduce the speed limit to 40 miles per hour---the costs of either course of action would be too high. In response to public demand, Congress in 1995 handed speed limit laws back to the individual states and allowed each state to decide its maximum speed to drive. Since then, 35 states increased their limits to 70 mph or higher (americansafetycouncil.com). If most Americans are willing to increase the risk of death in exchange for shorter driving times, the value we place on life has its limits. Be sure to realize that taxing externality producing activities may not eliminate damages. Taxes on these activities are not designed to eliminate externalities; they are simply meant to force decision-makers to consider the full costs of their decisions. Even if we assume that a tax correctly measures all the damage done, the decision maker may find it advantageous to continue causing the damage. The detergent manufacturer may find it most profitable to pay the tax and go on polluting the river. It can continue to pollute because the revenues from selling its product are sufficient to cover the cost of resources used and to compensate the damaged parties fully. In such a case, producing the product in spite of the pollution is "worth it" to society. It would be inefficient for the firm to stop polluting. Only if damage costs were very high would it make sense to stop. Thus, you can see the importance of proper measurement of damage costs. Reducing Damages to an Efficient Level Taxes also provide firms with an incentive to use the most efficient technology for dealing with damage. If a tax reflects true damages, and if it is reduced when damages are reduced, firms may choose to avoid or reduce the tax by using a different technology that causes less damage. Suppose our soap manufacturer is taxed $10,000 per month for polluting the river. If the soap plant can ship its waste to a disposal site elsewhere at a cost of $7,000 per month and thereby avoid the tax, it will do so. If a plant belching sulfides into the air can install "smoke scrubbers" that eliminate emissions for an amount less than the tax imposed for polluting the air, it will do so. The Incentive to Take Care and to Avoid Harm You should understand that all externalities involve at least two parties and that it is not always clear which party is "causing" the damage. Take our friends Harry and Jake. Harry enjoys music; Jake enjoys quiet. If Harry plays his music he imposes a cost on Jake. If Jake can force Harry to stop listening to music, he imposes a cost on Harry. Often, the best solution to an externality problem may not involve stopping the externality-generating activity. Suppose Jake and Harry's dormitory has a third resident, Pete. Pete hates silence and loves bluegrass music. The resident advisor on Harry's floor arranges for Pete and Jake to switch rooms. What was once an external cost has been transformed into an external benefit. Everyone is better off. Harry and Pete get to listen to music, and Jake gets his silence. Sometimes, the most efficient solution to an externality problem is for the damaged party to avoid the damage. However, if full compensation is paid by the damager, damaged parties may have no incentive to do so. Consider a laundry located next to the exhaust fans from the kitchen of a Chinese restaurant. Suppose damages run to $1,000 per month because the laundry must use special air filters in its dryers so that the clothes will not smell like Chinese food. The laundry looks around and finds a perfectly good alternative location away from the restaurant that rents for only $500 per month above its current rent. Without any compensation from the Chinese restaurant, the laundry will move and the total damage will be the $500 per month extra rent that it must pay. But if the restaurant compensates the laundry for damages of $1,000 a month, why should the laundry move? Under these conditions, a move is unlikely, even though it would be efficient. Subsidizing External Benefits Sometimes activities or decisions generate external benefits instead of cost, as in the case of Harry and Pete. Real estate investment provides another example. Investors who revitalize a downtown area---an old theater district in a big city, for example---provide benefits to many people, both in the city and in surrounding areas. Activities that provide such external social benefits may be subsidized at the margin to give direct decision makers an incentive to consider them. Just as ignoring social costs can lead to inefficient decisions, so too can ignoring social benefits. Government subsidies for housing and other development, either directly through specific expenditure programs or indirectly through tax exemptions, have been justified on such grounds. *CASE & FAIR, 2004, PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS, 7TH ED., PP. 310-313* end |

No comments:

Post a Comment