―

Household and Firm Behavior in the Macroeconomy: A Further Look*

(Part A)

by

Charles Lamson

In earlier posts, we considered the interactions of households, firms, and government in the goods, money, and labor markets. The macroeconomy is complicated, and there is a lot to learn about these interactions. To keep our discussions as uncomplicated as possible, we have so far assumed the simple behavior of households and firms---the two basic decision-making units in the economy. We assumed household consumption (C) depends only on income, and firms' planned investment (I) depends only on the interest rate. We did not consider that households make consumption and labor supply decisions simultaneously and that firms make investment and employment decisions simultaneously.

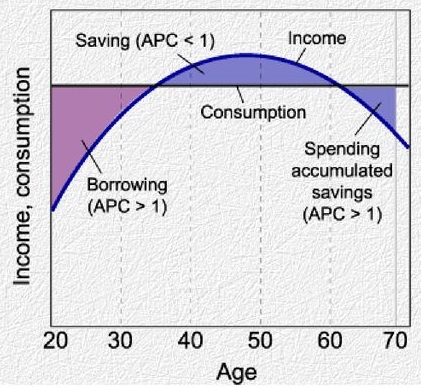

Now that we understand the basic interactions in the economy, we must relax these assumptions. In the next few posts, a more realistic picture of the influences on household consumption and labor supply decisions is presented. Then, we present a more detailed and realistic picture of the influences on firms' investment and employment decisions. We then use what we have learned to analyze more macroeconomic issues. Households: Consumption and Labor Supply Decisions Before discussing household behavior, let us review what we have learned so far. The Keynesian Theory of Consumption: A Review The assumption that household consumption (C) depends on income, which we have used as the basis of our analysis so far, is one that Keynes stressed in his General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. While Keynes believed many factors, including interest rates and wealth, are likely to influence the level of consumption spending, he focused on current income: The amount of aggregate consumption depends mainly on the amount of aggregate income. The fundamental psychological law, upon which we are entitled to depend with great confidence both . . . from our knowledge of human nature and from the detailed facts of experience, is that men [and women, too] are disposed, as a rule and on average, to increase their consumption as their incomes increase, but not by as much as the increase in their income. (John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936), p. 96) Keynes is making two points here. First, He suggests that consumption is a positive function of income. The more income you have, the more consuming you are likely to do. Except for a few rich misers who save scraps of soap and bits of string despite million-dollar incomes, this proposition make sense. Rich people typically consume more than poor people. Second, Keynes suggests, high-income households consume a smaller proportion of their income than low-income households. (If rich households consume relatively less of their incomes, then by definition they save a higher proportion of their incomes than poor households.) The proportion of income that households spend on consumption is measured by the average propensity to consume (APC) .The APC is defined as consumption divided. APC = C / Y If a household earns $30,000 per year and spends $25,000 (saving $5,000), it has an APC of $25,000 / $30,000, or .833. Keynes argues that people who earn, for example, $30,000, are likely to spend a larger portion of their income than those who earn $100,000. Although the idea that consumption depends on income is a useful starting point, it is far from a complete description of the consumption decision. We need to consider other theories of consumption. The Life-Cycle Theory of Consumption The life cycle theory of consumption is an extension of Keynes's theory. The idea of the life cycle theory is that people make lifetime consumption plans. By realizing that they are likely to earn more in their prime working years than they earn earlier or later, they make consumption decisions based on their expectations of lifetime income. People tend to consume less than they earn during their main working years---they save during those years---and they tend to consume more than they earn during their early and later years---they disssave, or use up savings, during those years. Students in medical school generally have very low current incomes, but few live in the poverty that those incomes might predict. Instead, they borrow now and plan to pay back later when their incomes improve. The lifetime income and compensation pattern of a representative individual is shown in Figure 1. As you can see, this person has a low income during the first part of her life, High income in the middle, and low-income again in retirement. Her income in retirement is not zero because she has income from sources other than her own labor---Social Security payments, interest and dividends, and so forth. The consumption path as drawn in Figure 1 is constant over the person's life. This is an extreme assumption, but it illustrates the point that the path of consumption over a lifetime is likely to be much more stable than the path of income. We consume an amount greater than our incomes during our early working careers. We do this by borrowing against future income, by taking out a car loan, a mortgage to buy a house, or a loan to pay for college. This debt is repaid when our incomes have risen and we can afford to use some of our income to pay off past borrowing without substantially lowering our consumption. The reverse is true for our retirement years. Here, too, our incomes are low. Because we consume less than we earn during our prime working years, we can save up a "nest-egg" that allows us to maintain an acceptable standard of living during retirement. Fluctuations in wealth are also an important component of the life cycle story. Many young households borrow in anticipation of higher income in the future. Some households actually have negative wealth---the value of their assets is less than the debts they owe. A household in its prime working years saves to pay off debts and to build up assets for its later years, when income typically goes down. Households whose assets are greater than the debts they owe have positive wealth. With its wage-earners retired, a household consumes its accumulated wealth. Generally speaking, wealth starts out negative, turns positive, and then approaches zero near the end of life. Wealth, therefore, is intimately linked to the cumulative saving and dissaving behavior of households. The key difference between the Keynesian theory of consumption and the life cycle theory is that the life cycle theory suggests consumption and saving decisions are likely to be based not just on current income but on expectations of future income as well. The consumption behavior of households immediately following World War II clearly supports the life cycle theory. Just after the war ended, income fell as wage earners moved out of war-related work. However, consumption spending did not fall commensurately, as Keynesian theory would predict. People expected to find jobs in other sectors eventually, and they did not adjust their consumption spending to the temporarily lower income they were earning in the meantime. The phrase permanent income is sometimes used to refer to the average level of a person's expected future income stream. If you expect your income will be high in the future (even though it may not be high now), your permanent income is said to be high. With this concept, we can sum up the life cycle theory by saying that current consumption decisions are likely to be based on permanent income instead of current income. This means that policy changes like tax-rate changes are likely to have more of an effect on household behavior if they are expected to be permanent instead of temporary. Although this enriches our understanding of the consumption behavior of households, the analysis is still missing something. What is missing is the other main decision of households: the labor supply decision, which we discuss in the next post. *CASE & FAIR, 2004, PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS, 7TH ED., PP. 607-609* end |

No comments:

Post a Comment