Mission Statement

The Rant's mission is to offer information that is useful in business administration, economics, finance, accounting, and everyday life. The mission of the People of God is to be salt of the earth and light of the world. This people is "a most sure seed of unity, hope, and salvation for the whole human race." Its destiny "is the Kingdom of God which has been begun by God himself on earth and which must be further extended until it has been brought to perfection by him at the end of time."

Thursday, February 28, 2019

Organizational Communication for Survival: An Analysis (part 5) 02/28 by CharlesXLamson | Management

Organizational Communication for Survival: An Analysis (part 5) 02/28 by CharlesXLamson | Management: 'A man's character may be learned from the adjectives which he habitually uses in conversation.' -Mark Twain

Performance Management: Changing Behavior That Drives Organizational Effectiveness (part 6)

Negative Reinforcement

by

Charles Lamson

Negative reinforcers increase behavior because people behave to escape or avoid a negative consequence. We shut the window to avoid the cold. We close the door to keep out insects. The difference in escape and avoidance is often defined in terms of whether we are proactive or reactive. The proactive response is to prevent the negative consequence from occurring (avoidance). We work late to prevent the negative consequence we know will happen if we are late with our project. Working late, then, is an avoidance behavior. We are reactive when we respond to a consequence that is occurring. We are cold so we close the window to stop the cold from continuing to enter the room (escape).

|

Negative reinforcement as a concept is somewhat confusing in that most people think of avoiding or escaping a consequence as not being a consequence. Usually all we see is the behavior because the behavior prevented the punishment from occurring, but it was the presence of that potential punisher that caused the escape or avoidance behavior. Negative reinforcement is usually the answer to the question, "Why are they doing that?" when there is no evidence of positive reinforcement. Usually you will find the punishment or penalty contingency when you investigate. Note that the contingency may be stated to reduce the frequency of a behavior ("If you do that one more time..."). Whatever you do to avoid or escape aversive consequences is driven by negative reinforcement.

Many times you will hear someone say, "I negatively reinforced that behavior." More often than not this is an incorrect statement. Most likely they punished or penalized some behavior. In many popular management books, negative reinforcement is often confused with punishment: The two terms are often presented as synonyms. They are far from synonyms. They produce the exact opposite effects. Negative reinforcement increases behavior; punishment and penalty decrease behavior.

Negative reinforcement consists of two separate conditions, both closely linked to possible punishment. The first condition occurs when a punishment or penalty contingency is in operation and your behavior terminates it. If you have ever been told "I know you need to go, but you must finish this job before you leave," your behavior was under the control of negative reinforcement. Your behavior terminates the unpleasant condition and you leave work as soon as the job is done. The second condition occurs when you receive a threat or warning such as, "If you do that again, you will be written up." You will work to avoid having that negative consequence occur. Whatever you do to avoid being written up is a negatively reinforced behavior.

After a number of years of not teaching the difference between positive and negative reinforcement, the writers of Performance Management discovered that when managers do not understand the difference, the majority of performance improvement efforts are driven by negative reinforcement. In addition, because negative reinforcement increases behavior, some managers do not see the need for positive reinforcement. In other words, as a result of using negative reinforcement to reach their goals, the managers may receive bonuses and other positive consequences. The problem is that once the consequence has been avoided, there is no motivation to do more. As long as the person does enough to keep the negative consequence from happening, he has maximized his effort.

William Edwards Deming was an American engineer, statistician, professor, author, lecturer, and management consultant. In his seminars, he told managers mangers to eliminate goals and standards. His observation was that they capped performance. He was observing that most goals and standards are achieved and maintained by negative reinforcement. He also told his audience to eliminate fear from the workplace. He did not use the term negative reinforcement as the method by which fear is maintained in the workplace, but that was, in effect, what he was describing. There is a cost to the organization that relies on this process either as a deliberate strategy or by a lack of awareness. Such settings, in Deming's words, "drive-in fear." Even though in some cases it may be difficult to see real differences in either rate or duration of responding under the two consequences, negative reinforcement almost always produces negative reports from employees as it relates to management and the workplace in general. When leaders endorse the use of negative consequences as the primary way to achieve organizational results, directly as an active participant or indirectly through policies and systems, it always produces ethical concerns and an organization that never performs up to its potential.

Although some behavior analytic research (e.g., Perone, 2003) suggests that it is often difficult to discriminate between results produced by positive reinforcement from those produced by negative reinforcement, these researchers rarely consider the contextual aspects of fear-driven organizations as part of the experiment. The writers would argue as well that such experiments cannot be generalized easily to the real world of work. Performance Management is not simply about obtaining results quickly or at high rates. How we obtain those results does count.

We encounter negative reinforcers many times every day. The behavior we display shows up as in driving fast to avoid being late. Children do their homework to avoid nagging from their parents. We go to the dentist to escape some pain or discomfort. We put on sunglasses to avoid the glare. Our legal system is almost exclusively a negative reinforcement system with few rewards in it for good behavior, only negative reinforcement and punishment for illegal behavior.

As you may understand by now, negative reinforcement requires some level of fear to be effective. The degree may be slight, such as fear of being embarrassed in a meeting, worrying about disappointing someone who is important to you, or fear of loss of income and status. This poses a problem for the company that relies too heavily on negative reinforcement to get work done. People do not want a job they are afraid of. They will escape such work by quitting. When they cannot usually because of economic circumstances, they will go to great lengths to avoid the feared consequence, including sometimes lying, cheating, and stealing. It is not unheard of that a manager or supervisor juggles the numbers to meet a quota or budget. In the case of Enron, executives went to the trouble of setting up companies for the purpose of hiding losses. We have known of cases where employees have carried production waste home rather than having it show up on a report. Absenteeism, turnover, and poor morale are other problems associated with excessive reliance on negative reinforcement.

If negative reinforcement is used to get a behavior started, positive reinforcement should be used to keep it going. The cost of managing by negative reinforcement is high. The cost is not only in terms of organizational profit, but it takes its toll on the managers as well as the employees they manage.

It must be pointed out that negative reinforcement is not bad; it just causes a predictable effect on behavior. When compliance is all that is needed, negative reinforcement can often get you there. When there is no behavior to positively reinforce you may need a negative reinforcement contingency such as "If you haven't finished this task by 5:00 pm, you must stay until it is completed" to get a behavior to positively reinforce. However, once the behavior has occurred under negative reinforcement control, to be most effective and efficient, the behavior must be positively reinforced as soon as it occurs.

*SOURCE: PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT: CHANGING BEHAVIOR THAT DRIVES ORGANIZATIONAL EFFECTIVENESS, 4TH ED., 2004, AUBREY C. DANIELS & JAMES E. DANIELS, PGS. 62-64*

end

|

Tuesday, February 26, 2019

Organizational Communication for Survival: An Analysis (part 4) 02/26 by CharlesXLamson | Management

Organizational Communication for Survival: An Analysis (part 4) 02/26 by CharlesXLamson | Management: 'Words - so innocent and powerless as they are, as standing in a dictionary, how potent for good and evil they become in the hands of one who knows how to combine them.' -Nathaniel Hawthorne 1st half: The Esoteric - Manly P. Hall's Analysis of Albert Pike's Morals and Dogma 2nd half: The Exoteric - Analysis of Organizational Communication for Survival

Organizational Communication for Survival: An Analysis (part 3) 02/25 by CharlesXLamson | Current Events

Organizational Communication for Survival: An Analysis (part 3) 02/25 by CharlesXLamson | Current Events: 1st half: The Esoteric - Part 3 of Manly P. Halls Analysis of Albert Pike's Morals and Dogma 2nd half: The Exoteric - Part 3 of Analysis of Organizational Communication for Survival

Monday, February 25, 2019

Performance Management: Changing Behavior That Drives Organizational Effectiveness (part 5)

The ABC Model

by

Charles Lamson

The ABC Model is based on scientific research in behavior analysis. So in this post we will begin our scientific exposition of why people do what they do. Here we begin to look at behavior from a much more precise perspective. If we are to build processes and systems that maximize the return on assets employed, we must know as much as possible about the essential building block: behavior.

The ABC Model is also known as the three-term contingency - Antecedent, Behavior and Consequence. The three-term contingency refers to the fact that every behavior is affected by something that comes before it and by what it produces.

We continuously respond to signals and signs in our internal and external environment (antecedents) that lead to some action on our part (behavior), which in turn leads to something happening as a result of our action (consequence). As illustrated by Figure 1, a consequence may be an antecedent for another instance of the same behavior. We have all experienced the situation where someone offers us chips or candy (antecedent). We take one piece and eat it (behavior). It tastes so good (consequence/antecedent) that we take another and eat it (behavior). Unfortunately, for most of us this is repeated too many times every day.

Figure 1 ABC Model

It is important to know that antecedents and consequences are not equal in their effect on behavior. Simply put, antecedents draw their power from consequences. To use an analogy from electricity, consequences charge antecedents. As you will see throughout this analysis, common sense experience often teaches us the wrong thing. If you observe people in problem-solving situations, you will find that their behavior indicates that they believe antecedents are the most effective way to change behavior.

By far, the most common way of trying to implement change in an organization is to change antecedents rather than consequences. We train, explain, involve people in decision making, have meetings, send out clarifying memos, et cetera. We do these things in spite of the fact that the closest thing we have to a behavioral law is that behavior is a function of its consequences. In helping executives understand why their organizational change initiatives did not live up to expectations, it is almost always due to the fact that they implemented change with no significant difference in the consequences to the people involved in the change. Billions of dollars are wasted every year by such tactics.

If you are to grow any organization or even maintain it over time, an understanding of behavioral consequences is necessary to make maximum progress. We use the term behavioral consequences to differentiate it from the more common use of the word consequences. Understanding the use of the complete ABC Model is important if you are to arrange conditions and change behavior efficiently, effectively, and for the longer term.

Consequences

Behavioral consequences are events that follow a behavior and change the probability that the behavior will recur in the future. Consequences are the single most effective tool a manager has for improving employee performance and morale. As amazing as it may sound, there is one straightforward answer to the problems of poor quality, low productivity, high costs, and disgruntled employees - behavioral consequences.

In hundreds of offices and plants, hospitals, hotels, restaurants, and other kinds of organizations, the ineffective use of consequences has created and maintained poor performance and low morale. But providing appropriate consequences has produced dramatic increases in the bottom line and employee satisfaction.

Here you will be introduced to the various consequences and how they operate in the everyday work environment. You will see that consequences affect performance whether you attempt to manage them or not. If you do not manage consequences, they will simply operate unsystematically and often in ways that are counterproductive, because consequences are always occurring and always impacting behavior. Think of it this way: We are not always aware of how gravity is affecting what we do, but we know that it is. Similarly, consequences always affect our behavior, whether we are aware of it, believe it, or understand it.

There are two basic consequences: those that increase behavior and those that decrease it.

The Effects of Consequences

Some consequences increase the probability that a behavior will occur and some decrease the probability that a behavior will occur. Although a casual examination seems to indicate that some behavioral consequences have no effect on behavior, close examination shows that not to be the case. It is just that the change in the behavior is too small to be detected by casual observation.

Behavior followed by consequences - this pattern repeats itself many, many times throughout every day. It is so obvious, so commonplace, we have learned to ignore it. For example, put money in a candy machine and press the button. Usually, the candy comes tumbling out. But what if no candy comes out? Will you use the machine again? You might try again but if it still failed to work, you would probably stop. The behavior of putting money in that machine depends on the consequence - receiving candy. Remove that consequence and behavior changes. You will probably seek another machine that works - one that produces the consequence you want - or, you will forget it and go on to something else.

Every behavior has a consequence that affects its future probability. That is, consequences do not simply influence what someone does; they control it. To understand why people do what they do, instead of asking "Why did they do that?" ask "What happens to them when they do that?" When you understand the consequences, you are most likely to understand the behavior.

Consequences come in many forms and endless varieties. What people do to us, what they say to us, what they give us, and what they don't give us can all affect our behavior. As you will see, both the presence of a consequence and the absence of a consequence affect behavior.

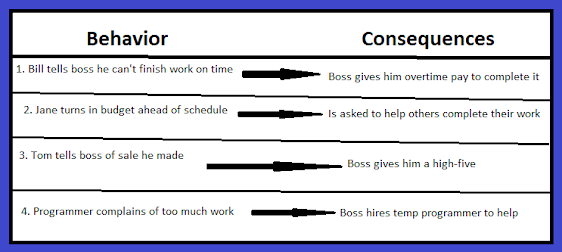

Take a look at the examples in Figure 2. In each of the examples, something has happened to the individuals after their behavior. We cannot say how these consequences will affect other performers in similar situations because different people often respond differently to the same consequence. If Bill does not like to work overtime, the consequence of having to work late or on the weekend may increase the likelihood that he will complete his work on time in the future. On the other hand, if he needs the money, he may be less likely to complete work on schedule in the future. The point is that whether a consequence has a positive or negative effect on behavior can only be determined by its effect on future behavior.

Figure 2 Consequences Follow Behavior

*SOURCE: PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT: CHANGING BEHAVIOR THAT DRIVES ORGANIZATIONAL EFFECTIVENESS, 4TH ED., 2004, AUBREY C. DANIELS & JAMES E. DANIELS, PGS. 49-51*

end

|

Saturday, February 23, 2019

Organizational Communication for Survival: An Analysis (part 2) 02/23 by CharlesXLamson | Management

Organizational Communication for Survival: An Analysis (part 2) 02/23 by CharlesXLamson | Management: 'The best way to solve problems and to fight against war is through dialogue.' -Malala Yousafzai

Friday, February 22, 2019

Performance Management: Changing Behavior That Drives Organizational Effectiveness (part 4)

TOP STORIES

Search Results

Ohio River continues to rise, officials warn against more flooding

KFVS-12 hours ago

Ohio River continues to rise, officials warn against more flooding ... The Ohio Riverhas already forced the closure of the casino and about half a ...

Flooding may force closure of US 51 Ohio River bridge between ...

WPSD Local 6-17 hours ago

WICKLIFFE, KY — The Kentucky Transportation Cabinet says floodwaters may force the U.S. 51 Ohio River bridge connecting Wickliffe, ...

Overflowing Ohio, Mississippi Rivers Raise Specter of Midwest Flooding

Bloomberg-20 hours ago

An onslaught of rains over several months has raised water levels for the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, threatening floods along banks in the ...

Forget the Mind Games; Deal with Behavior

by

Charles Lamson

What is going on in employees' heads is not the business of managers. The employees' behavior is our business. We do not hire people's knowledge (that which is inside the brains or minds of people); we hire their behavior that demonstrates what we define as their knowledge. In business, the employee enters into an understanding or a contract, explicit or implicit, with the employer that says that he or she will do what the organization requires. It is legitimate to require people to change their behavior at work. It is not legitimate to require to require them to change their minds.

Trying to solve a business problem by trying to change thoughts and feelings is a very inefficient approach to changing performance. While everyone has thoughts and feelings, and those thoughts and feelings seem concrete enough to the individual, we do not attempt to manipulate them in our approach. In conducting scientific research, thoughts and feelings are difficult to get at and study. Although much has been written and much research has been, and is being, conducted on thinking and feeling, those elements are not the primary subject of the book Performance Management. Granted, the thoughts and feelings of each of us are important. If such private events are shared or demonstrated in ways that we might describe as "emotional" (a loud outburst, crying, laughing, yelling) or in other overt ways, then they become relevant to our discussion, since they are observable. We know that if people are treated well, they will often say that they feel good about their work environment. If people are encouraged to act in ways that reduce differences between themselves and their colleagues, they will often report a reduction in thoughts of exclusion. That is how thoughts and feelings function in relation to behavior. Managers and colleagues are interested in how others think and feel, but again, we only know them by what we are told or what we see. We ask, "What could you have been thinking when you did that? or say, "You act like you don't feel well" or "You act like you are angry all the time" or "You act happy." We can only assume those things from observing some overt behavior of the person.

We infer thoughts and feelings of others from behavior; there is no other way to know that thoughts and feelings even exist. So why not focus on what can be known rather than what we can only speculate about? A little reflection reveals that when we say someone has a bad attitude or a good attitude toward work we are basing our statement on what he is doing and then using what we infer as an attitude to be the internal cause of behavior. This reasoning is circular and has no place in science because it is false logic and counterproductive.

If thoughts and feelings do not translate at some point to overt behavior they have no value to the business. Some would say that decision making and problem solving are mental activities. It would be helpful if we could capture brilliant thought, but we can only observe the overt actions and the ultimate result; then we use that data to improve decisions and solutions of others. We can describe exemplars in this area based on the value that their effective decisions (actions) have on solutions. If we study them closely, we can find patterns that may be worthy of replicating.

Trying to solve a business problem by first trying to change thoughts and feelings is usually not efficient. It is much more productive to change behaviors that would result in different thoughts and feelings (i.e. behavior under the skin). Contrary to popular psychological thought and practice, you do not always need to get what is bothering you out into the open before you can solve a problem. While people have negative thoughts and feelings about things that have happened to them in the past, dealing with them is not necessary to change behavior. Forgetting and forgiveness can happen without reliving the past. The best way to change someone's feeling or thoughts is to change their behavior. If you are doing things that lead to positive outcomes for you, that are successful, that make you smile or laugh, you no doubt feel good and think positively about your situation. Where what you are doing is unsuccessful or leads to criticism and rejection, you feel badly and think negatively.

The writers (Aubrey C. Daniels & James E. Daniels) contend that when the methods suggested in this book are implemented correctly, people will have positive thoughts and feelings about what they do and about the place in which they do it. With that said, however, it is worth pointing out that behaviors we typically label as emotional (negative) are of considerable concern to management. Generally these are behaviors of such intensity and are so disruptive and inappropriate that we are forced to attend to them immediately. Our society has many examples of employees who reacted to some aversive consequence(s) at work in a very destructive way. For example, a manager displaying repeated anger in front of his or her employees will create an environment of fear. How management acts to prevent or correct such behaviors is important. The key to successfully dealing with overtly negative behaviors is important. The key to successfully dealing with overtly negative behaviors is to investigate behavior-consequence relationships that produce the reaction and then, if possible, make the necessary changes.

*SOURCE: PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT: CHANGING BEHAVIOR THAT DRIVES ORGANIZATIONAL EFFECTIVENESS, 4TH ED., 2004, AUBREY C. DANIELS & JAMES E. DANIELS, PGS. 37-39*

end

|

Thursday, February 21, 2019

Organizational Communication for Survival: An Analysis (part 1) 02/21 by CharlesXLamson | Management

Organizational Communication for Survival: An Analysis (part 1) 02/21 by CharlesXLamson | Management: 'Don't tell me the moon is shining; show me the glint of light on broken glass.' -Anton Chekhov

Performance Management: Changing Behavior That Drives Organizational Effectiveness (part 3)

Separating Behavior from Non-Behavior

by

Charles Lamson

What Behavior Is Not

If you will remember that behavior is an observable action, you will avoid most of the egregious errors in managing behavior. The following is a list of the four most common assumptions that cause out-of-control variability in management systems. If you can control these management inputs, you will go a long way toward creating the behaviors you want.

Generalities are not behavior.

Unfortunately, many people who talk about behavior have a very imprecise definition of the term. Performance appraisal forms often ask the manager to discuss the employee's behavior and then give them key words such as professionalism, creativity, teamwork, enthusiasm, or quality of communications. Some managers talk about having a commitment to safety as if it were a behavior. Additionally, terms such as selling, monitoring, checking, delegating, supervising, managing, taking ownership, and being proactive fail the test for behaviors. They do not describe what you can observe someone doing.

When we use imprecise terms to tell people what to do, we have to expect a great deal of variability in how they interpret our directives. Many managers think that they are being clear when they tell their direct reports things like, "I don't care how you do it. Just get it done!" They assume that the person understands (from policy, procedures and precedents) their meaning. We have even heard managers say things like, "If I have to tell them how to do their job, I don't need them." The literature on failed companies is filled with cases where the senior manager gave direction only in general terms. Enron senior management wanted entrepreneurs, resulting in managers who started unfunded and unscrutinized ventures that robbed funds from the revenue producing units of the company as well as from the honest majority of the company's employees. One of the worst forms of management is when the boss asks for something and gives as his/her criterion for success, "I'll know it when I see it."

Attitudes are not behavior.

Business seems to have a considerable interest in areas such as safety awareness, quality consciousness, and cost consciousness. These general descriptions are often referred to as attitudes. Such descriptions are particularly difficult to work with because they are assumed to come from a state of mind. They are not behaviors but refer to a vast collection of tasks and behaviors. Additionally, different people using these terms are usually referring to different tasks and behaviors. When we refer to safety consciousness, we may want people to duck as they walk under overhead pipes, clean up spills, put on safety glasses, and warn others of safety hazards. Quality conscious may mean doing extra engineering tests on materials and designs, inspecting incoming raw materials for defects, cleaning the assembly area and frequently checking machine settings. Cost conscious may mean turning off equipment when finished, cleaning and lubricating equipment daily, and checking settings at the beginning of a job. For an engineer, cost consciousness may mean documenting engineering change orders, calculating loads on schedule, and recording time charged to the job. Terms and phrases denoting attitudes always fail the measurability and activity criteria for behavior.

States are not behavior.

It is also important to differentiate between states and behaviors. A state is a static condition that exists as a result of behavior. Wearing safety glasses is a state; putting on safety glasses is a behavior. Sleeping is a state; getting in bed is a behavior. Sitting in a chair is a state; sitting down is a behavior, getting up is a behavior. States do not require action. Action is usually required to get to a state but, once there, no action is required. Once you fall asleep, no action is required to remain asleep. Once you sit in a chair, no action is required to stay there. The problem is that the action (behavior) that created the state may not be one of which you would approve. Behavioral consultant Courtney Mills recounts the following: A distribution manager I was working with wanted his crew to put their safety glasses on as soon as they walked through the warehouse door. He explained that he never reinforced someone for wearing safety glasses (a state) unless he knew they put the glasses on at the warehouse door. He insisted on the standard for recognition because one day when he went into the warehouse, he saw an employee hurriedly putting his glasses on when he saw the manager coming. The manager said later that he almost reinforced the employee for wearing the glasses, but thought better of it because he did not reinforce the behavior of putting on his safety glasses only when he sees a manager coming.

Values are not behaviors.

Defining mission, vision, and values has long been a leadership function. Mission, vision, and values are activities that help companies articulate their chief functions or activities (mission), their direction, focus or impact anticipated for the future (vision) and what is acceptable in terms of how they treat one another and go after business success (values). Articulating mission, vision, and values, however, has had little impact on behavior in most organizations as they still have articulated and communicated these things very well only to end up in trouble with both the law and/or stockholders. Executives have completed mergers only to realize later that they had no expertise in the acquired business or that the acquired business was not a strategic fit. Employees have been caught lying, cheating, and stealing to get customers, reduce costs, or increase profit or stock price. It is no longer sufficient to post mission, vision, and values on walls. Unless the leadership actively manages the behaviors they describe in these documents, they could be permitting internal counterproductive competition and other destructive actions. Activities such as creating behavior-based mission and values statements can produce worthwhile guidelines for business; but, without an assessment of the true behavioral impact, those documents can also breed employee cynicism and deceit.

A value like honesty is not a behavior; it is a group of behaviors defined by their impact on the observer. You may consider yourself as honest but others may see you as being dishonest because of what they know, or believe, that you said or did not say, or by the way you talk about what you do. Many organizations have failed to change values because they think that values are behaviors. Teamwork, for example, is a value that most organizations have. It is certainly not a behavior, but many behaviors. The criticism "We don't work as a team" could mean many things. Until teamwork is broken down into behaviors and/or tasks that describe it in measurable and observable terms, you may be very frustrated in your efforts to increase teamwork. Your organization may list speaking up when there is a problem as a value, but employees find that those who do speak up are told to "Get on board" or "Stop criticizing" or in other ways given the message that the value of open communication and the action that should go along with it are two very different things. Stated values are not behavior, and values that cannot be described in specific behavioral terms are almost impossible to instill in an organization. If you know the behaviors that are necessary to produce valuable results in your organization, you know more than most managers and are much closer to improving organizational efficiency and effectiveness.

*SOURCE: PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT: CHANGING BEHAVIOR THAT DRIVES ORGANIZATIONAL EFFECTIVENESS, 4TH ED., 2004, AUBREY C. DANIELS & JAMES E. DANIELS, PGS. 35-37*

end

|

Wednesday, February 20, 2019

Conclusion of Strategic Organizational Communication in a Global Economy 02/18 by CharlesXLamson | Current Events

Conclusion of Strategic Organizational Communication in a Global Economy 02/18 by CharlesXLamson | Current Events: 'Trust is the glue of life. It's the most essential ingredient in effective communication. It's the foundational principle that holds all relationships.' -Stephen Covey

Monday, February 18, 2019

Performance Management: Changing Behavior That Drives Organizational Effectiveness (part 2)

Web results

The Value of Performance Management to Organizations

by

Charles Lamson

Organizations use Performance Management for many reasons. However, the seven reasons that follow highlight the value of PM to business, industry, and government.

|

1. PM works.

PM is practical. It is not generalized abstract theory that suggests ways to think about problems; it is a set of specific actions for increasing desired performance and decreasing undesired performance. The PM procedures have been validated against measurable results in a wide variety of applications.

The writers of Performance Management contend that firms using performance management have reported returns on investment ranging from 4:1 to 60:1 in the first year. Successful applications have occurred in a wide range of organizations, from manufacturing and service to software development and research. Job-specific applications range from sales and safety to customer service and vendor performance. In a survey of the research literature, Duncan (1989) reports the average improvement in PM applications is 69 percent.

2. PM produces short-term as well as long-term results.

Mitchell Fein (1981), the creator of a gain-sharing system called Improshare, says that if you go onto the production floor, into the office, or into the lab and do the right things, you will see a performance change in 15 minutes. He is not entirely correct. If you do the right things, you will, in many cases, see the effect immediately! In fact, laboratory research (Foster & Taylor, 1962; Mal, McCall, Newland and Cummins, 1993; Stoddard, Serma & McIlvane, 1994) has shown that animals and humans can learn or change after receiving only one reinforcer!

Most initiatives introduced into organizations make no claim that results can be expected quickly. In fact, their advocates warn that changes should not be expected for a year or more. Few managers can stick to any motivational program or system that takes several years to show results.

The writers of Performance Management go on to say on page 12 that results are produced quickly using the principles of Performance Management. Once mastered, the applications of PM to accelerating organizational performance are so useful that they become habitual and the only way to manage performance. An increasing number of companies using PM are still getting consistent improvement after more than 20 years.

If you try to solve a problem using the procedures and techniques described in this book and do not see changes in performance within the first 10 to 15 data points, you can bet you are doing something wrong, the writers contend. The good thing about this approach is you will know the steps to take to correct the problem. To sustain commitment and enthusiasm, people must see short- and long-term results.

3. PM requires no formal psychological training.

Performance management is supported by thousands of experimental and applied research studies in laboratories, universities, schools, clinics, hospitals, and homes since the early 1950s. This research is based on the pioneering work of the American psychologist, B. F. Skinner.

Dr. Skinner rejected the belief that in order to work effectively with people you must first understand their deep-seated anxieties, feelings, and motives. He took the position that the only way you can know people is by observing how they behave (what they do or say). In his book About Behaviorism, he states, "No matter how defective a behavioral account may be, we must remember that mentalistic explanations explain nothing" (Skinner, 1974, p. 224). It explains nothing to say that a person is lazy or unmotivated or passive-aggressive. These explanations require interpretation of the actions of performers (as though any of us can read the minds of others). Labels such as lazy make the work of improving performance much more complex than many managers see themselves as capable of handling. Applying labels to actions, rather than just describing what is seen or heard, removes objectivity and lessens or destroys the possibility for rapid performance improvement.

Because the PM approach focuses on behavior rather than mental activity, some critics have said it denies thoughts and feelings. Performance Management and the science from which it is derived do not deny thoughts and feelings but consider them just more behavior to be explained. Thoughts and feelings are private behaviors. The methods used to study and understand overt behavior applies to private behavior as well. The difference is that the only person who can use those methods on internal thoughts and feelings is the individual who has them. Until private thoughts are shared through spoken words, they are not available to others. Once any private event is made public, then others can study the overt expression just as with any other behavior.

Performance Management accepts people as they are, not as they were. Because it deals with the here and now, managers do not need to pry into people's private lives or their histories in order to manage them effectively. Managers do not need to know how people were potty trained, that they hate their fathers, or that they are middle children.

Because PM deals with the present, everybody can learn its techniques. In other words, you do not need to be a psychologist, psychiatrist, or a mind reader. As a matter of fact everyone, even if unaware of doing so, makes use of and is influenced by the laws of behavior. Unfortunately, in many cases, people use these laws haphazardly and ineffectively.

The principles of behavior are so simple that infants learn to use them to gain control over their parents in a very short period of time. Notice how quickly people respond when a baby cries or smiles. However, the paradox is that even though the basics are simple, they are not obvious. As a result, we often inadvertently teach people to do what we do not want them to. Consider an example from home. A child asks for candy an hour before dinner and you say no because it will spoil his appetite. He cries loudly for 10 minutes and you give the candy to him to stop the crying. In the short-term, you have stopped the crying (may be seen as a good thing), but in reality, you have increased the likelihood that the child will cry again in the future when he wants something, especially candy. Not only that, but you might have punished his asking for something rather than crying for it. This applies to our own behavior as well. We learn and do things that are sometimes, in the larger picture, not good for us even though we find them rewarding. For example, eating fast food that is high in fat, cholesterol, carbohydrates, salt or sugar is more pleasurable immediately, but eating fast food has long-term detrimental effects on our health. We are all subject to the laws of learning. You can avoid this mistake by learning how such situations occur and how to change them in a productive way.

4. PM is a system for maximizing all kinds of performance.

Because PM is based on knowledge acquired through a scientific study of behavior, the principles are applicable to behavior wherever it occurs. This means that PM applies to people, wherever they work and no matter what they do. The applicability of PM to routine and easily measured jobs is apparent with a basic understanding of the principles. However, it may be easier to see how PM applies to production jobs than to jobs where the main outcome is creativity such as in research or engineering, or to complex organizational problems such as bringing about a cultural change or creating autonomous work groups.

Be assured that if one or more people are involved in any activity, PM can enable them to work consistently at their full potential. These principles work whether the performer is the president of the company or the custodian, whether the target is an R&D group working on telecommunications systems for future generations or a group of textile employees producing a product that the company has been making for 50 years. PM principles have been shown effective in companies as small as 5 employees and as large as 50,000 or more employees.

5. PM creates an enjoyable place in which to work.

Most people agree that if you are doing something you enjoy, you are more likely to perform better than if you do not like what you are doing. Unfortunately some managers have the notion that fun and work do not mix. Indeed in many cases the way people have fun at work is at the expense of the work rather than through it. Everyone knows of employees who engage in off-task behavior such as horseplay, practical jokes, playing computer games, surfing the Internet, or other forms of goofing off.

If, however, the fun comes from doing the work, then management should be preoccupied with how to increase fun rather than how to eliminate it. A manufacturing executive recently said, "Sales and marketing folks know how to have fun at work. In manufacturing, we haven't had much fun; no, we haven't had any fun. We've got to change that."

Fun and work are so antithetical to some managers that this subject may turn them off. But, as you will see, when you have fun that is directly related to your primary job tasks, you will find that quality, productivity, cost and customer service can all be dramatically improved.

6. PM can be used to enhance relationships at work, at home, and in the community.

While this book focuses on the workplace, the writers use many examples from everyday life because they are easy to relate to, and they highlight the universality of the approach. Indeed, many managers have been convinced of the power of the approach by applying PM to a difficult problem at home. Imagine using PM to increase your child's completion of chores at home or to increase the volunteers' participation at your school fundraiser, all by making the activities more enjoyable for everyone involved!

7. PM is an open system.

PM includes no motivational tricks. You will learn nothing in this book that you would not want everybody in your organization to know. You will learn nothing that is illegal, immoral, or unethical. Because of the stable number of positive reinforcers needed to sustain high levels of performance, high performance organizations teach these principles to everyone so that employees at all levels can facilitate the performance of others as well as their own. Just as managers influence the performance of the people they supervise, employees influence the performance of managers by the same process. Nothing about the principles states that reinforcement only works down the organizational hierarchy. Reinforcement works on behavior. It does not matter who performs the behavior. Therefore, PM works equally well up and across the organization. Performance Management suggests only methods for changing another person's performance that you would enjoy having done for you in the same circumstance. Therefore, there is no need for secret plans to improve performance. On the contrary, every reason exists to be open and honest in all relationships at work. In the final analysis, changing performance with PM will result in everybody getting more of what they want from work.

To be continued...

*SOURCE: PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT: CHANGING BEHAVIOR THAT DRIVES ORGANIZATIONAL EFFECTIVENESS, 4TH ED., 2004, AUBREY C. DANIELS & JAMES E. DANIELS, PGS. 10-17*

end

|

Friday, February 15, 2019

Performance Management: Changing Behavior That Drives Organizational Effectiveness (part 1)

Introduction to Performance Management

by

Charles Lamson

In Wealth and Poverty, author George Gilder (1981) states:

...productivity differences between workers doing the same job in a particular plant are likely to vary as much as four to one and differences as high as 50 percent can arise between plants commanding identical equipment and the same size labor force that is paid identically. Matters of management, motivation, and spirit - and their effects on willingness to innovate and seek new knowledge - dwarf all measurable inputs in accounting for productive efficiency, both for individuals and groups and for management and labor (p. 40).

|

The organization that can isolate effective people management practices, processes, and procedures and implement them efficiently will have a significant competitive advantage over those that cannot. Performance Management (PM) gives you a precise system for managing performance at work, and is based on scientific knowledge of human behavior.

Performance Management: Science and Values

As you read this analysis, you will see many instances of the science of behavior analysis applied with precision and effectiveness. Once you master the technology, you will have choices about how you achieve your performance objectives. What you work to achieve, how you set up conditions for success, what you reinforce, and what you punish - all such actions contain ethical elements.

None of us are free from the moral and legal implications of what we do. The business of managing people is very serious indeed but it can and should be fun more often than not. When done well, nothing managers do is of greater importance than helping employees become and remain successful while having a good time doing it.

What is Performance Management?

Performance Management is a technology for creating a workplace that brings out the best in people while generating the highest value for the organization. The techniques and practices of PM are derived from the field called behavior analysis, the term describing the scientific study of behavior analysis that seeks to extend the findings of laboratory research to everyday problems.

The field of Applied Behavior Analysis was clearly defined by Baer, Wolf, and Risley (1968). Its subject matter is human behavior: why we act as we do, how we acquire habits, and how we lose them; in other words, why we do the things we do and how we can change them, if change is needed. Performance Management, as defined in this book which is the subject of this analysis (Performance Management by Aubrey C. Daniels and James E. Daniels), is a branch of Applied Behavior Analysis that focuses on the workplace.

To understand behavior, behavior analysts use the same scientific methods that the physical sciences employ: precise definition of the behavior under study, experimentation, and consistent replication of the experimental findings. Basic research in this area has been conducted for over a century (e.g., Thorndike, 1898; Watson, 1913; Skinner, 1936). However, applied research has been conducted only since the 1950s. Business, industrial, and government applications began in the late 1960s.

Compared with most of the established sciences, behavior analysis is very young, but much has been learned in a short period of time. Many of the principles of learning are relatively well understood at this point. Although much remains to be learned, current knowledge has been used to solve thousands of business problems in the last four decades. Many of these problems plagued organizations for a long time and in some cases were thought to be unsolvable. For example, in a television tube manufacturing plant two quality problems that had troubled the plant for over a year were solved in one day! Also, many businesses such as restaurants, hotels, call centers, and other minimum wage occupations accept high turnover rates as a necessary cost of doing business. Yet, the use of PM methods has cut turnover in just 90 days, or so the writers of this book contend.

To be continued...

*SOURCE: PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT: CHANGING BEHAVIOR THAT DRIVES ORGANIZATIONAL EFFECTIVENESS, 4TH ED., 2004, AUBREY C. DANIELS, JAMES E. DANIELS, PGS. 4-7*

end

|

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

-

That's what hip-hop is: It's sociology and English put to a beat, you know. Talib Kweli Inequalities of Social Class (...

-

I'm double majoring in social studies - which is sociology, anthropology, economics, and philosophy - and African-American studies. Yara...