I had always looked down on sociology as this arriviste discipline. It didn't have the noble history of English and history as a subject. But once I had a little exposure to it, I said, 'Hey, here's the key. Here's the key to understanding life and all its forms.'

Societies and Nations

(Part A)

by

Charles Lamson

Populations and Societies

The remarkable growth of the world's human population is the great biological success story of the last million years. Throughout most of the evolution of the human species, the world's population remained relatively small and constant. At the end of the Neolithic period, about 8000 BCE, there were an estimated 5 million to 10 million humans, concentrated mainly in the Middle East, East Africa, southern Europe, and a few fertile river basins in India, China, Latin America, and Central America. The overall range of human existence is much wider---populations were moving north as the last Ice Age receded about 12,000 years ago---but the human population was nowhere near as widely distributed as it is today. By the time of Jesus there were an estimated 200 million people on the earth, and by the start of the Industrial Age, about the year 1650, there were an estimated 500 million. By 1945, however, the population had reached about 2.3 billion, and it is now 7.8 billion as of March 2020, according to my Google Assistant. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_population).

What explains the shape of this population curve, the gradual rise in the world's population during the late Stone Age, the increasing rate of growth in the early millennia of recorded history, the explosive growth after 1650? The answers have to do with the changing production technologies of society and their ever-increasing ability to sustain their populations, not only those directly involved in acquiring food but the ever larger numbers of non-food producers as well. In other words, human population growth is related to the shift from hunting and gathering to agriculture and, later, to industrial production as the chief means of supplying people with the necessities of life.

The First Million Years: Hunting and Gathering

A human lifetime is no more than a twinkling in time. What are seventy or eighty years compared with the billions of years of the earth's existence? What is one generation compared with the millions of years of human social evolution? Yet many of us hope to leave some mark on society, perhaps to change it for the better, to ease some suffering, to increase productivity, to fight racism and ignorance. This is a radical change from the worldview of our ancestors. The idea that people can shape their society or even enjoy adequate shelter and ample meals is widely accepted today. But for most of human history mere survival was the primary motivator of human action, and thus a fatalistic acceptance of human frailty in the face of overwhelming natural forces was the dominant worldview.

For most of the first million years of human evolution, human societies where developing from those of primates. Populations were small because humans, like other primates, lived on wild animals and plants. These sources of food are easily used up and their supply fluctuates greatly, and as a result periods of starvation or gnawing hunger might alternate with bouts of gorging on sudden "manna from heaven" in the form of game or berries. Thus the hunting-and-gathering life that characterized the earliest human populations could support only extremely small societies; most human societies therefore had no more than about 60 members.

Archaeological evidence indicates that some hunting-and-gathering societies began to develop permanent settlements long before the advent of agriculture. The emergence of farming was one of the changes that accelerated human social evolution, but in parts of what is now Europe and the Middle East there were stable settlements of hunter-gatherers as early as 30,000 to 20,000 years ago. These rather large and complex societies were most firmly established in the area that is now Israel at the end of the last Ice Age, some 13,000 to 12,000 years ago.

Despite the slow pace of human evolution until about 35,000 years ago, some astonishing physical and social changes occurred during that long period, changes that enabled human life to take the forms it does today. Among them where the following:

By the end of the last Ice Age, many aspects of this evolutionary process were more or less complete. Human societies had fully developed languages and a social structure based on the family and the band. To be cast out of the band for some wrongdoing---that is, to be considered a deviant person---usually meant total banishment from the society and eventual death, either by starvation or as a result of aggression by members of another society.

The lives of the hunter-gatherers were far more subject to the pressures of adaption to the natural environment than has been true in any subsequent form of society. Individual survival was usually subordinated to that of the group. If there were too many children to feed, some were killed or left to die; when the old became and infirm or weak, they often chose death so as not to diminish the chances of the others. Thus the frail Eskimo grandfather or grandmother wandered off into the snowy night to meet the polar bear and the great spirit. Additional thousands of years of social evolution would pass before the idea that every person could and should survive, prosper, and die with dignity would even occur to our ancestors.

The Transition to Agriculture

For some time before the advent a plow-and-harvest agriculture in the Middle East and the Far East, hunting and gathering societies were supplementing their diets with foods acquired through domestication of plants and animals. In this way they were able to avoid the alternation of periods of feast and famine caused by reliance on animal prey. Karl Marx was the first social theorist to observe that social revolutions like the shift to agriculture or industrial production are never merely the result of technological innovations such as the plow or the steam engine. The origins of new forms of society are to be found within the old ones. New social orders do not simply burst upon the scene but are created out of the problems faced by the old order. Thus, as they experimented with domestication of animals and planting of crops, some hunting-and-gathering societies were evolving into nomadic shepherding or pastoral societies in which bands follow the flocks of animals. Others were developing into horticultural societies in which the women raised seed crops and the men combed the territory for game and fish.

Regarding this momentous change in the material basis of human survival, the historian William McNeil made the following observation:

The seed-bearing grasses ancestral to modern cultivated grains probably grew wild eight or nine thousand years ago in the hill country between Anatolia and the Zagros Mountains as varieties of wheat and barley continue to do today. If so, we can imagine that from time immemorial the women of those regions searched out patches of wheat and barley grasses when the seeds were ripe and gathered the wild harvest by hand or with the help of simple cutting tools. Such women may gradually have discovered methods for assisting the growth of grain, e.g., by pulling out competing plants, and it is likely that primitive sickles were invented to speed the harvest long before agriculture in the stricter sense came to be practiced. (The Rise and Fall of the West: A History of the Human Community, 1963, p. 12)As a result of these and other innovations, agriculture became the productive basis of human societies. Pastoral societies spread quickly throughout the uplands and grasslands of Africa, Northern Asia, Europe, and the Western Hemisphere, and grain-producing societies arose in the fertile river valleys of Mesopotamia, India, China---and somewhat later---Central and South America. Mixed societies of shepherds and marginal farmers wandered over the lands between the upland pastures and the lowland farms.

The First Large-Scale Societies We have reached the beginning of recorded history (around 4000 BC), which was marked by the rise of the ancient civilizations of Sumer, Babylonia, China and Japan, and the Maya, Incas, and Aztecs. The detailed study of these societies is the province of archaeology, history, and classics. Sociologists need to know as much as possible about the earliest large-scale societies because many contemporary social institutions (e.g., government and religion) and most areas of severe social conflict (e.g. class and ethnic conflict) developed sometime in the agrarian epoch---between 3000 BC and a 1600 AD.

FIGURE 4 Depiction of Tenochtitlan (Pre-Colombian Mexico City)

From the standpoint of social evolution, the following dimensions of agrarian societies are the most notable (R.S. Braidwood, Prehistoric Man, 1967):

New Social Structures Freed from direct dependence on on domesticated species of plants and animals, agrarian societies developed far more complex social structures than were possible in simpler societies. Hunting-and-gathering societies divided labor primarily according to age and sex, but in agricultural societies labor was divided in new ways to perform more specialized tasks. People who had been conquered in war might be enslaved and assigned the most difficult or least desirable work. Priests controlled the society's religious life, and from the priestly class there emerged a class of hereditary rulers who, as the society became larger and more complex, assumed the status of pharaoh or emperor. Artisans with special skills---in the making of armaments or buildings, for example---usually formed another class. And far more numerous than any of these classes where the tillers of the soil, the common agricultural workers and their dependents.

The process whereby the members of the society are sorted into different statuses and classes based on differences in wealth, power, and prestige is called social stratification. in general, societies may be open, so that a person who was not born into a particular status may gain entry to that status, or closed, with each status accessible only by birth. A key characteristic of agrarian societies is that their stratification systems became extremely closed and rigid. Because most people were needed in the fields, there were few opportunities for people to move from one level of society to another. These therefore we're closed societies.

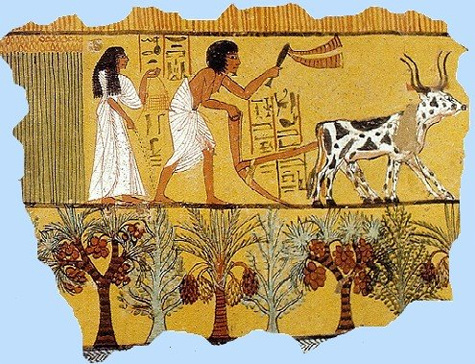

The emergence of agrarian societies was based largely on the development of new, more efficient production technologies. Of these, the plow and irrigation are among the most important. The ancient agrarian empires of Egypt, Rome, and China are examples of societies in which irrigation made possible the production of large food surpluses, which in turn permitted the emergence of central governments led by pharaohs and emperors, priests and soldiers. Indeed, some sociologists have argued that because large-scale irrigation systems required a great deal of coordination, their development led to the evolution of imperial courts and such institutions as slavery which coerced large numbers of agrarian workers into forced labor (K.Wittfogel, 1957, Oriental Despotism: A Comparative Study of Total Power).

FIGURE 5 Irrigation in Ancient Egypt Permits Emergence of Central Govrnment Led by Pharaohs, Priests, and Soldiers

By the 15th century the world's population was organized into a wide variety of societies with many different types of cultures and civilizations. The area where the earliest civilizations emerged are to this day the most densely inhabited parts of the world. In 1500 these civilizations were marked by their ability to produce food surpluses through the use of the plow, domesticated animals, wheels, and carts. Above all, they are marked by the importance of towns and cities as centers of administration and religious practice. Although the Mayan and Incan civilizations did not have the wheel or the plow, their advanced systems of astronomy, art, and writing make a strong argument for their inclusion as world civilizations.

The explorations led by Portugal, Spain, and England in the 16th and 17th centuries resulted in conquest and European settlement in many parts of the Western Hemisphere and Africa. Conquest caused radical disruptions in the internal development of the world's cultures and civilizations. But even more drastic would be the changes caused by the Industrial Revolution of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The Industrial Revolution

In 1650, when Holland, Spain, and England were the world's principal trading nations, the population of England was approximately 10 million, of which about 90% earned a livelihood through farming of one kind or another. Just two hundred years later, in 1850, the English population had soared to more than 30 million, with less than 20% at work in fields, barnes, and granaries. England had become the world's first industrial society and the center of an empire that spanned the globe.

A similar transformation occurred in the United States. In 1860, on the eve of the Civil War, there were about 30 million people in the United States. Ninety percent of that population, a people considered quite backward by the rapidly industrializing English, were farmers or people who worked in occupations directly related to farming. A mere 100 years in 1960, only about eight percent of Americans were farmers or agricultural workers, yet they were able to produce enough to feed a population exceeding 200 million. As of 2008, less than 2 percent of the population is directly employed in agriculture (Agriculture in the United States - Wikipedia). These dramatic changes in England and America and in other nations as well occurred as a result of the Industrial Revolution.

The Industrial Revolution is often associated with Innovations in energy production, especially the steam engine. But the shift from an agrarian to an industrial society did not happen simply as a result of technological advances. Rather, the Industrial Revolution was made possible by the rise of a new social order known as capitalism. This new way of organizing production originated in nation-states, which engaged in international trade, exploration, and warfare. Above all, the Industrial Revolution depended on the development of markets, social structures that would function to regulate the supply of and demand for goods and services throughout the world.

The transition from an agrarian to an industrial society affects every aspect of social life. It changes the structure of society in several ways of which the following are among the most significant:

These are only some of the important features of industrial societies. There are many others, which we analyze throughout this analysis. I will present research that shows how the types of jobs people find and the ways in which they spend their leisure time change as technology advances and their expectations change. We will look into the ways in which other major institutions (especially the family) adapt to the changes created by the Industrial Revolution. In fact, we will continually return to the Industrial Revolution as a major force in our times.

FIGURE 7 Onward to the Postindustrial Society!

The Theory of Postindustrial Society The United States and most other societies that experienced industrialization in earlier periods are now condemned by sociologists to be "postindustrial societies." Even though these societies continue to be important producers of industrial goods like steel, glass, aluminum, and many other products, their industrial plants are highly automated and employment in manufacturing is no longer the largest sector of the economy.

Postindustrial or not, the United States and the European nations are still among the world's industrial societies because they are major producers of manufactured goods. However, it should be noted that the businesses that produce those goods are dwindling in number because of the effects of the Industrial Revolution in other areas of the world. Also, for the first time in U.S. history the number of jobs in services exceeds that of jobs in goods-producing industries. Far more jobs are created in restaurants and hotels each year than in steel mills and other kinds of factories (J.D. Kasarda, 1989, Urban Industrial Transition and the Underclass. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 501, 26-47). In addition there is an increasing demand for highly educated and trained workers in new industries that deal with high-speed transmission of information. Computers and telecommunications technologies are surely produced by "industries," but they are not the type of mass-employment "smokestack" industries that were the hallmark of earlier stages of the Industrial Revolution.

The theory of post-industrial society explores why those fundamental changes have come about and their impact, not only on post industrial societies themselves but also on the cultures of other societies. There are also many questions about what will happen as the world societies become more and more interdependent and decisions made in metropolitan centers like Tokyo, Los Angeles, and London affect the lives of villagers in the most remote parts of the world. We will return to the issues raised by theories of industrialization and the emergence of a post-industrial society throughout analysis. For it is clear that while the most advanced and powerful nations are undergoing an economic transformation, in many other parts of the world the Industrial Revolution is in full swing, and in still other, more remote areas older forms of agrarianism and tribalism continue to thrive.

*MAIN SOURCE: SOCIOLOGY IN A CHANGING WORLD, 6TH ED., 2003, WILLIAM KORNBLUM, PP. 92-100*

end

|

No comments:

Post a Comment