Human well-being is not a random phenomenon. It depends on many factors - ranging from genetics and neurobiology to sociology and economics. But, clearly, there are scientific truths to be known about how we can flourish in this world. Wherever we can have an impact on the well-being of others, questions of morality apply.

Sam Harris

Socialization

(Part B)

By

Charles Lamson

Nature and Nurture

Throughout recorded history there have been intense debates over what aspects of behavior are human nature and what aspects can be intentionally shaped through nurture or socialization. During all the centuries of pre-scientific thought, the human body was thought to be influenced by the planets, the moon, and the sun, or by the brain, heart, and liver. In the ancient world and continuing into the Middle Ages, blood, bile, phlegm, and other bodily fluids were thought to control people's moods and affect their personalities. Human behavior and health could also be affected by evil spirits or witches. While they are no longer dominant explanations of human behavior. Some of these ideas never entirely disappeared.

|

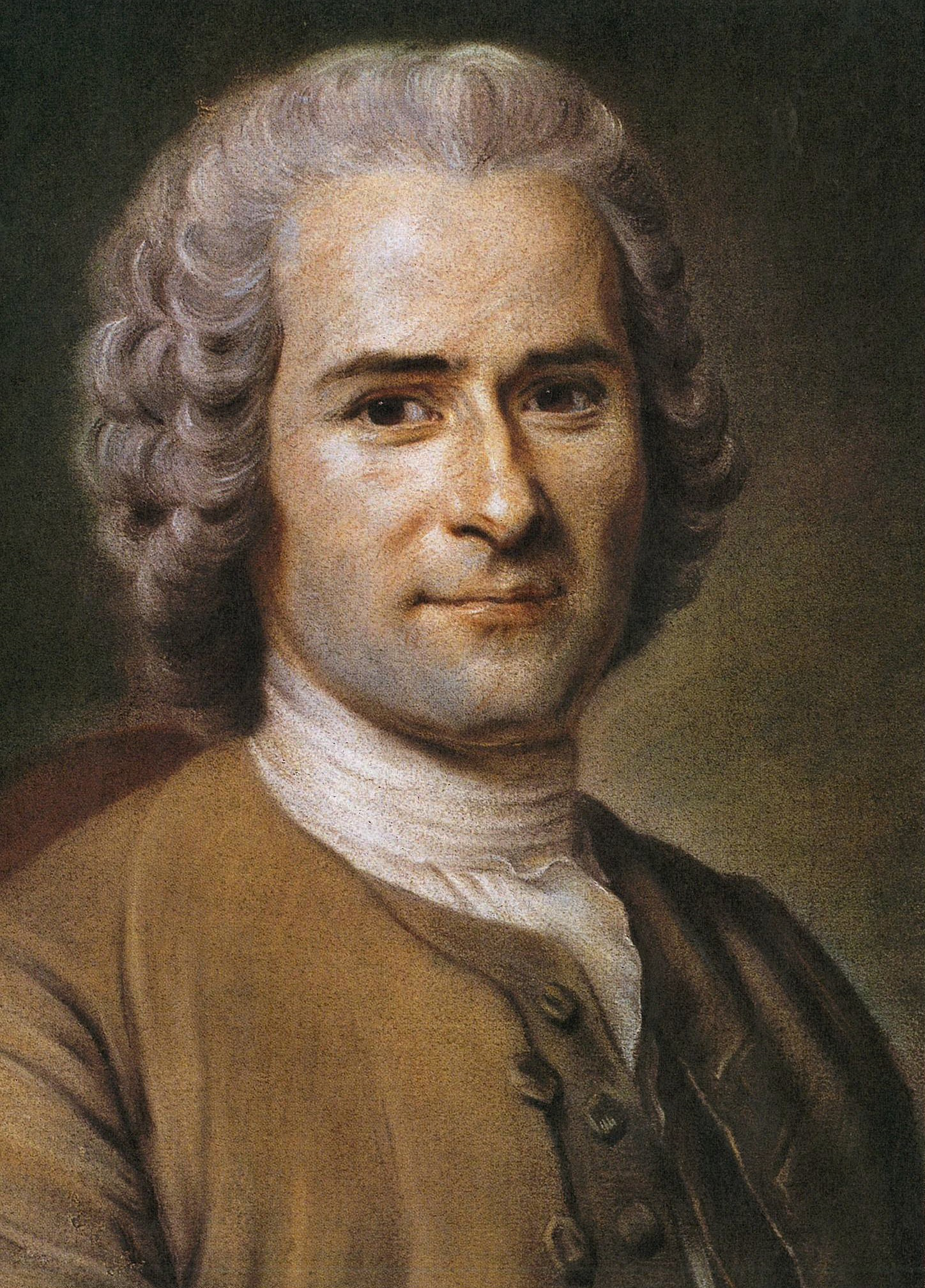

| EXHIBIT 1 Jean-Jacques Rousseau

In the eighteenth century a new and radical idea of the "natural man" emerged. The idea that humans inherently possess qualities such as wisdom and rationality, which are damaged in the process of socialization, took hold in the imaginations of many educated people. Social philosophers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau (see Exhibit 1) believed that if only human society could be improved, people would emerge with fewer emotional scars and limitations of spirit. This belief was based on the enthusiasm created by scientific discoveries, which would free humans from ignorance and superstition, and new forms of social organization like democracy and capitalism, which would unleash new social forces that would produce wealth and destroy obsolete social forms like aristocracy.

In the United States, Thomas Jefferson applied these ideas in developing the educational and governmental institutions of the new nation. Much later, in the 19th century, Karl Marx and other social theorists applied the same basic idea of human predictability and they are criticisms of capitalism. A revolutionary new society, they predicted. would overturn the worst effect of capitalism and finally realize Rousseau's promise that a superior society could produce superior people. As these examples indicate, many of the most renowned thinkers of the last two centuries have rejected the belief that nature places strict limits on what humans can achieve.

The Freudian Revolution

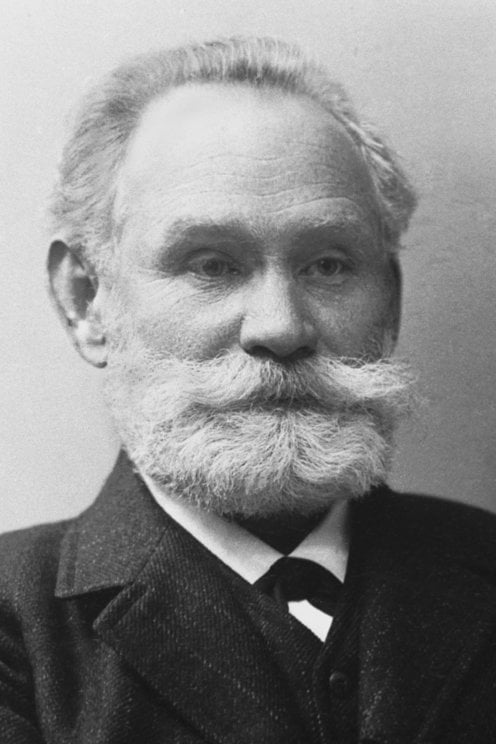

Sigmund Freud (see Exhibit 2) was the first social scientist to develop a theory that addresses both the nature and nurture aspects of human existence (Nagel, 1994, May 12. Freud's Permanent Revolution. New York Review of Books, pp. 34-39; Robinson, 1994. Freud and His Critics). For Freud, the social self develops primarily in the family, wherein the infant is gradually forced to control its biological functions and needs: sucking, eating, defecation, genital stimulation, warmth, sleep, and so on. Freud shocked the straight-faced intellectuals of his day by arguing that infants have sexual urges and by showing that these aspects of the self are the primary targets of early socialization---that the infant is taught in many ways to delay physical gratification and to channel its biological urges into socially accepted forms of behavior.

Freud's model of the personality is derived from his view of the socialization process. Freud divided the personality into three functional areas, or interrelated parts, that permit the self to function well in society. The part from which the infants unsocialized drives arise is termed the id. The moral codes of adults, especially parents, become incorporated into the part of the personality that Freud called the superego. Freud thought of this part of the personality as consisting of all the internalized norms, values, and feelings that are taught in the socialization process. In addition to the id and the superego, the personality, as Freud described it, has a third vital element, the ego. The ego is our conception of our self in relation to others, in contrast with the id, which represents self-centeredness in its purest form. To have a "strong ego" is to be self-confident and able to accept criticism. To have a "weak ego" is to need continual support from others. (The popular expression that someone "has a big ego" and demands constant attention actually signals a lack of ego strength in the Freudian sense.)

In the growth of the personality, according to Freud, the formation of the ego or social self is critical. But it does not occur without a great deal of conflict. The conflict between the infant's basic biological urges and society's need for a socialized person becomes evident very early. Freud believed that the individual's major personality traits (security or insecurity, fears and longings, ways of interacting with others) are formed in the conflict that occurs when parents insist that the infant control its biological urges. This conflict, Freud believed, is most severe between the child and the same-sex parent. The infant wishes to receive pleasure, especially sexual stimulation, from the opposite-sex parent and therefore is competing with the same-sex parent. To become more attractive to the opposite-sex parent, the infant attempts to imitate the same-sex parent. Thus for Freud the same-sex parent is the most powerful socializing influence on the growing child, for reasons related to the biological differences and attractions between the child and the opposite-sex parent.

EXHIBIT 2 Sigmund Freud

Contemporary sociologists who are influenced by Freud's biologically and socially based theories have used his concept of same-sex attraction and imitation of the same-sex parent's behavior to explain differences between men and women. Alice Ross (1977), for instance, argues that women's shared experience of menstruation and childbearing creates a strong bond between mothers and daughters. Nancy Chodorow (1978) claims that women's earliest experiences with their mothers tend to convince them that a woman is fulfilled by becoming a mother in her turn; thus women are socialized from a very early age to "reproduce motherhood." Research on socialization has shown that men also are strongly influenced by the same-sex parent. Fathers often serve as models of behavior whom boys will emulate throughout their lives (A. Ross. The Biosocial Basis of Parenting. Daedalus; N. Chodorow. The Reproduction of Mothering: Psychoanalysis and the Sociology of Gender).

Freud's theory includes the idea that the conflicts of childhood reappear throughout life in ways that the individual cannot predict. The demands of the superego ("conscience") and the childish desires of the id are always threatening to disrupt the functioning of the ego, especially in families in which normal levels of conflict are either exaggerated or suppressed. Note, however, that Freud focused on the traditional family, consisting of mother, father, and children. The more families depart from this conventional form, the more we need to question the adequacy of Freudian socialization Theory.

Behaviorism

In the early decades of the twentieth century Freud's theory was challenged by a different branch of social scientific thought, known as behaviorism. In contrast to Freud and others who saw many human qualities as innate or biologically determined (nature), behaviorists saw the individual as a blank slate, that could be written upon through socialization. In other words, individual behavior could be determined entirely through social processes (nurture). Behaviorism asserts that individual behavior is not determined by instincts or any other hardware in the individual's brain or glands. Instead all behavior is learned.

Behaviorism traces its origins to the work of the Russian psychologist Ivan Pavlov (1927). Pavlov's experiments with dogs and humans revealed that behavior that had been thought to be entirely instinctual could in fact be shaped or conditioned by learning situations. Pavlov's dog, one of the most famous subjects in the history of psychology, was conditioned to salivate at the sound of a bell. The dog would normally salivate whenever food was presented to it. In his experiment, Pavlov rang a bell whenever the dog was fed. Soon the dog would salivate at the sound of a bell alone, thereby showing that cell salivation, which had always seemed to be a purely biological reflex, could be a conditioned, or learned, response as well (I. Pavlov. Conditional Reflexes: An Investigation of the Physiological Activity of the Cerebral Cortex).

EXHIBIT 3 Ivan Pavlov

The American psychologist John B. Watson carried on Pavlov's work with an equally famous series of experiments on "Little Albert," an 11 month old boy. Watson conditioned Albert to fear baby toys that were thought to be inherently cute and cuddly, such as stuffed white rabbits. By presenting these objects to Albert at the same time that he frightened him with a loud noise (i.e., a negative stimulus), Watson showed that the baby could be conditioned to fear any fuzzy white object, including Santa Claus's beard. He also showed that through the systematic presentation of white objects accompanied by positive stimuli, he could extinguish Albert's fear and cause him to like white objects again.

On the basis of his findings Watson wrote:

Give me a dozen healthy infants, well formed, in my own specified world to bring them up in and I'll guarantee to take any one at random and train him to become any type of specialist I might select---doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant chief and, yes, even beggar-man and thief, regardless of his talents, pensions, tendencies, abilities, locations, and race of his ancestors. (1930. Behaviorism, p. 104)

For the behaviorist, in other words, nature is irrelevant and nurture are all important.

Behaviorists who followed Watson---the most famous being B. F. Skinner (see below, Exhibit 4)---developed even more effective ways of shaping individual behavior. In his 1976 book Walden Two, Skinner reasoned that in order to avoid failures in socialization it is necessary to completely control all the learning that goes on in the child's social environment. Sociologists are critical of the notion that it is possible to control the world of the developing person. They argue that while the behaviorist may show us how some types of social learning take place, psychological research often does not deal with real social environment. It has very little to say about what is actually learned in different social contexts, how it is learned or not learned, and the influences of different social situations on the individual throughout life (F. Elkin & G. Handel, 1989. The Child and Society: The Process of Socialization). One type of situation that has been of interest to sociologists studying socialization processes is that of the child reared in extreme isolation.

/bf-skinner-56a792c95f9b58b7d0ebd009.jpg)

EXHIBIT 4 B. F. Skinner

Isolated Children

The idea that children might be raised apart from society, or that they could be reared by wolves or chimpanzees or some other social animal, has fascinated people since ancient times. Romulus and Remus, the legendary founders of Rome, were said to have been raised by a wolf. The story of Tarzan, a boy of noble birth who was abandoned in Africa and raised by apes, became a worldwide bestseller early in the twentieth century and has intrigued readers and movie audiences ever since. However, modern studies of children who experienced extreme cast doubt on the possibility that a truly unsocialized person can exist.

Throughout the 19th century and much of the 20th, the discovery of a feral ("untamed") child always seemed to promise new insights into the relationship between biological capabilities and socialization, or nature and nurture (K. Davis, 1947. Final Note on a Case of Extreme Isolation. American Journal of Sociology. 52, 432-437). Social scientists looked on each case of a child raised in extreme isolation as a natural experiment that might reveal the effects of lack of socialization on child development. Once the child had been brought under proper care, studies were undertaken to determine how well he or she functioned. These studies showed that victims of severe isolation are able to learn, but that they do so far more slowly than children who have not been isolated (L. Malson, 1972. Wolf Children and the Problem of Human Nature).

The case of Genie is representative of this line of research. Jeanne was born to a psychotic father and a blind and highly dependent mother. For the first 11 years of her life she was strapped to a potty chair in an isolated room of the couple's suburban Los Angeles home. From birth she had almost no contact with other people. She was not toilet trained, and food was pushed toward her through a slit in the door of her room. When she was discovered by child welfare authorities after the mother told neighbors about the child's existence, the father committed suicide. Genie was placed in the custody of a team of medical personnel and child development researchers.

In the first few weeks after she was discovered, everyone who observed Genie was shocked. At first glance she looked like a normal child, with dark hair and pink cheeks and a placid demeanor. Very quickly, however, it became clear that she was defeat severely impaired. She walked awkwardly and was unable to dress herself. She had virtually no language ability---at most, she knew a few words, which she pronounced in an incomprehensible babble. She spit continuously and masturbated with no sense of social propriety. In short, she was a clear case of a child who had been deprived of social learning and in consequence was severely retarded in her individual and social development. She was alive, but she was not a social being in any real sense of the term. She had not developed a sense of self, nor had she the basic ability to communicate that comes with language learning.

EXHIBIT 5 Feral Child Genie

For years researcher Susan Curtiss studied Genie's slow progress toward language learning. In her book Genie: A Psycholinguistic Study of a Modern-Day "Wild Child," written in 1977, Curtiss showed that Genie could learn many more words than a mentally retarded person and would be expected to learn, but that she had great difficulty with the more complex rules of grammar that come naturally to a child who learns language in a social world. Genie's language remained in the shortened form characteristic of people who learn a language late in life. Most significant, Genie never mastered the language of social interaction. She had great difficulty with words such as hello and thank you, although she could make her wants and feelings known with nonverbal cues. Although tests showed that in many ways Genie was highly intelligent, her language abilities never advanced beyond those of a third grader. Genie gradually learned to adhere to social norms, but she never became a truly social being. Eventually the scientist who worked with her concluded that her most severe deprivation---the one that was the primary cause of her inability to become fully social and to master language---was her lack of emotional learning and especially her feelings of loss and lack of love. Never fully capable of Independent Living, Jeannie has spent her life in a home for developmentally disabled adults (Rymer, 1992a, 1992b. A Silent Childhood. New Yorker).

The Need For Love

All studies of isolated children point to the undeniable need for nurturing in early childhood. They all show that extreme isolation is associated with profound retardation in the acquisition of language and social skills. However, they cannot establish causality because it is always possible that the child may have been retarded at birth. Despite their lack of firm conclusions, studies of children reared in extreme isolation have pointed researchers in an important direction: They suggest that lack of parental attention can result in retardation and early death. This conclusion receives further support from studies of children reared in orphanages and other residential care facilities, which have shown that such children are more likely to develop emotional problems and to be retarded in their language development than comparable children reared by their parents (S. R. Kohler & B. J. Freeman, 1994. Analysis of Environmental Deprivation: Cognitive and Social Development in Romanian Orphans. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Sciences; Spitz, 1945. Hospitalism: An Inquiry into the Genesis of Psychiatric Conditions in Early Childhood. In A. Freud (Ed.). The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child).

In a series of studies that have become classics in the field of socialization and child development, the primate psychologist Harry Harlow, as shown below (Exhibit 6), showed that infant monkeys reared apart from other monkeys never learned how to interact with other monkeys (1986. From Learning to Love and 1962 November. Social Deprivation in Monkeys. Scientific American, pp. 137-147); they could not refrain from aggressive behavior when they were brought into group situations. When females who had been reared apart from their mothers became mothers themselves, they tended to act in what Harlow described as a "ghastly fashion" toward their young. In some cases they even crushed their babies heads with their teeth before handlers could intervene. Although it is risky to generalize from monkey behavior to that of humans, these studies of the effects of lack of nurturance bear a striking resemblance to studies of child abuse in humans. This research generally shows that one of the best predictors of child abuse is whether the parent was also abused as a child (K. Kenniston, 1965. Social Change and Youth in America. In E. H. Erikson (Ed.), The Challenge of Youth and 1977. All Our Children; Polansky, et al, 1981. Damaged Parents: An Anatomy of Child Neglect; Talbot, 1998, May 24. Attachment Theory: The Ultimate Experiment. New York Times Magazine. pp. 24-30).

EXHIBIT 6 Harry Harlow and His Monkey

These findings confirm our intuitive knowledge that nurturance and parental love play a profound, those still incompletely understood, role in the development of the individual as a social being. These and related findings offer support for social policies that seek to enrich the socialization process with nurturance from other caring adults---for example, in early education programs. Yet many researchers and policymakers remain convinced that biological traits place limits on what individuals can achieve, regardless of the kind of nurturance they receive. In recent years proponents of this view focused on the controversial question of how intelligence effects achievement.

A Sociological Summary

Neither extreme of the nature-nurture debate presents a complete picture of socialization. Nature may endow individuals with greater or lesser innate abilities, yet despite those differences most people learn to function as social beings. And although humans have an infinite capacity to learn behaviors of all kinds, through socialization they learn that particular behavior is required to function within their own culture and society. Nevertheless, the nature-nurture debate will endure and will continue to stimulate new research on the biological and psychological basis of behavior. In the meantime, most sociological research will focus on the following hypotheses:

*MAIN SOURCE: SOCIOLOGY IN A CHANGING WORLD, 6TH ED., 2003, WILLIAM KORNBLUM, PP. 119-123*

end

|

No comments:

Post a Comment