by

Charles Lamson

Consistent leadership is not using the same leadership style all the time, but using the style appropriate for the followers' level of readiness in such a way that followers understand why they are getting a certain behavior, a certain style from the leader. Inconsistent leadership is using the same style in every situation. Managers are inconsistent if they smile and respond supportively all the time---whether their followers are doing their job well or not.

|

To be really consistent managers must behave the same way in similar situations for all parties concerned. Thus, a consistent manager would not discipline one follower when that person makes a costly mistake, but not another staff member, and vice versa. It is also important for managers to lead their followers the same way in similar circumstances, even when it is inconvenient---when they don't have time or when they don't feel like it.

Some managers are consistent only when it is convenient. They may praise and support their people when they feel like it and redirect and supervise their activities when they have time. This attitude leads to problems. Parents are probably the worst in this regard. For example, suppose Wendy and Walt get upset when their children argue with each other and are willing to clamp down on them when it happens. However, there are exceptions to their consistency in this area. If they are rushing off to a dinner party, they will generally not deal with the children's fighting. Or, if they are in the supermarket with the kids, they will frequently permit behavior they would normally not allow because they are uncomfortable disciplining the children in public. Because children are continually testing the boundaries or limits of their behavior (they want to know what they can do and cannot do), Walt and Wendy's kids soon learn that they should not fight with each other except when Mom and Dad are in a hurry to go out or when they're in a store. Thus, unless parents and managers are willing to be consistent even when it is inconvenient, they may actually be encouraging misbehavior.

Another thing that frequently happens is that, instead of using appropriate leader behavior matched with follower readiness, performance, and demonstrated ability, leaders assign privileges on the basis of chronological age or gender. For example, a parent may permit an irresponsible 17-year-old son to stay out until 2:00 A.M. but make a very responsible 15-year-old daughter come home by midnight.

One of the ideas behind the old definition of consistency was the belief that your behavior as a manager must be consistent with your attitudes. This idea bothered some people who were heavily involved with the human relations or sensitivity-training movement. They believed that if you care about people and have positive assumptions about them, you should also treat them in high relationship ways and seldom in directive or controlling ways.

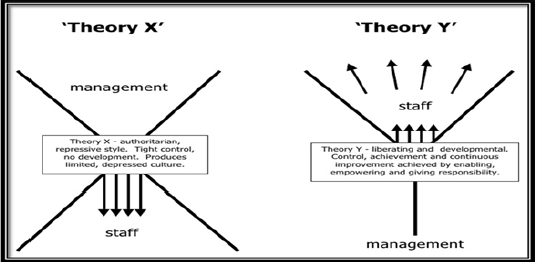

Much of this problem stemmed from the failure of some theories and practitioners to distinguish between an attitudinal model and a behavioral model. For example, in examining the dimensions of the Managerial Grid (Figure 2 - concern for production and concern for people) and Reddin's 3-D Managerial Style theory (Figure 1 - task orientation and relationship orientation), one can see that all these dimensions appear to be attitudinal. Concern or orientation is a feeling or an emotion toward something. The same can be said about McGregor's Theory X and Theory Y (Figure 3) assumptions about human nature. Theory X describes negative feelings about the nature of people, and Theory Y describes positive feelings. These are all models that describe attitudes and feelings.

Figure 1 Reddin's 3-D Managerial Style

Figure 2 Managerial Grid

Figure 3 Theory X and Theory Y

On the other hand, dimensions of the Hersey-Blanchard Tridimensional Leader Effectiveness model (task behavior and relationship behavior) are dimensions of observed behavior. Thus, the Tridimensional Leader Effectiveness model describes how people behave, where as the Managerial Grid, the 3-D Management Style theory, and Theory X-Theory Y describe attitudes or predispositions toward production and people.

Although attitudinal models and the Tridimensional Leader Effectiveness model examine different aspects of leadership, they are not incompatible. A conflict develops only when behavioral assumptions are drawn from analysis of the attitudinal dimension of models such as the Managerial Grid and theories such as Theory X-Theory Y. First, it is very difficult to predict behavior from attitudes and values. In fact, it has been found that you can actually do a much better job of predicting values or attitudes from behavior. If you want to know what's in a person's heart, look at what that person does. Look at the person's behavior.

For example, assume that a manager has a very high concern for product quality. Does that tell you what that manager is going to do about it? No. One manager who has a high concern for product quality may say the following: "Don't even talk to me about quality. I don't want to make any changes right now." In other words, the person engages in avoidance or withdrawal (low relationship behavior and low task behavior). Another manager who has a very high concern for product quality may meet with employees and tell them what to do, how to do it, when to do it, and where to do it (high task behavior and low relationship behavior). A third manager who has high concern for product quality might visit a department saying, "Gee, I'm sorry you have problems. Do you want to talk to me about it? Let's discuss it. Gosh, I'm sympathetic" (high relationship behavior and low task behavior). Finally, another manager who has a high concern for product quality might try to provide high amounts of both task behavior and relationship behavior in helping the department form self-managed teams.

What I am suggesting is that the same value set can evoke a variety of behaviors. You cannot easily predict behaviors from values. A look at one of the simplest models in the behavioral sciences may help to emphasize this point of view. The model is the S-O-R (a stimulus directed toward an organism produces some response). The trap many humanistic trainers fall into is to suggest that we assess the effectiveness of management by looking at the stimulus, or the leadership style. In other words, they say there are good styles and bad styles. What we are saying is that if you are going to assess performance, you don't evaluate the stimulus, you assess the results---the response. It is here that we need to make assessments in terms of performance. There is no best leadership style, or stimulus. Any leadership style can be effective or ineffective depending on the response that style gets in a particular situation. We also have to look at the impact the leaders get in a particular situation. We also have to look at the impact the leaders have on the human resources. It's not enough to have a tremendous amount of productivity for the next 6 months. Your methods may upset your people, causing them to leave and join your competitors. You also have to be concerned about what impact you are having on your followers, on developing their competency and their commitment. So when we talk about response, or results, we're talking about output and impact on the human resources.

There is another reason to be careful about making behavioral assumptions from attitudinal measures. Although high concern for both production and people and positive Theory Y assumptions about human nature are basic ingredients for effective managers, it may be appropriate for managers to engage in a variety of behaviors as they face different problems in their involvement. Therefore, the high task-high relationship style often associated with the the Managerial Grid 9-9 team management style or the paricipative high relationship-low task behavior that is often argued as consistent with Theory Y may not always be appropriate.

For example, if a manager's employees can take responsibility for themselves, the appropriate style of leadership for working with them may be low task and low relationship. In this case, the manager delegates to those employees the responsibility of planning, organizing, and controlling their own operation. The manager plays a background role, providing socioemotion support only when necessary. In using this style appropriately, the manager would not be "impoverished" (low concern for both people and production). In fact, delegating to competent and confident people is the best way a manager can demonstrate a 9-9 attitude and Theory Y assumptions about human nature. The same is true for using a directive high task-low relationship style. Sometimes the best way you can show your concern for people and production (9-9) is to direct, control, and closely supervise their behavior when they are insecure and don't have the skills yet to perform their job.

Summary

Empirical studies tend to show that there is no normative (best) style of leadership. Effective leaders adapt their leader behavior to meet the needs of their followers and the particular environment. If their followers are different, they must be treated differently. Therefore, effectiveness depends on the leader, the followers, and other situational variables. Anyone who is interested in effectiveness as a leader must give serious thought to both behavioral and environmental considerations.

*SOURCE: MANAGEMENT OF ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOR: LEADING HUMAN RESOURCES, 8TH ED., 2001, PAUL HERSEY, KENNETH H. BLANCHARD, DEWEY E. JOHNSON, PGS. 121-124*

end

|

No comments:

Post a Comment