Mission Statement

The Rant's mission is to offer information that is useful in business administration, economics, finance, accounting, and everyday life. The mission of the People of God is to be salt of the earth and light of the world. This people is "a most sure seed of unity, hope, and salvation for the whole human race." Its destiny "is the Kingdom of God which has been begun by God himself on earth and which must be further extended until it has been brought to perfection by him at the end of time."

Friday, July 31, 2020

Sunday, July 26, 2020

Sociological Imagination: How to Gain Wisdom about the Society in which We All Participate and for Whose Future We Are All Responsible (part 30)

Thus Christian humanism is as indispensable to the Christian way of life as Christian ethics and a Christian sociology.

Inequalities of Race and Ethnicity

by

Charles Lamson

The Meaning of Race and Ethnicity

How can we explain prejudice and racial discrimination and the inequalities they engender? And how can we measure their effects on individuals and social institutions? Many social scientists focus their research on why some groups in a society have been subordinated and the consequences of that subordination for them and their children. The effects of various forms of subordination, such as slavery, expulsion, and discrimination, on a society's patterns of inequality are at the center of the study of race and ethnicity.

Given the ever-changing diversity of the population, racial and ethnic relations in the United States are always complex and sometimes marked by overt conflict. No sooner does the society appear to be making some progress in combating prejudice and discrimination than new issues and problems appear.

The United States is not unique In the extent to which inequality and hostility among its ethnic and racial groups result in severe social problems.

Given its importance throughout the world, it is no wonder that the study of racial and ethnic relations has always been a major subfield of sociology. Most societies include minority groups, people who are defined as different according to the majority's perceptions of racial or cultural differences. And in many societies sociologists try to get at the origins of these fears and groundless distinctions that categorize people as different and influence their life chances, often in dramatic ways.

In the next couple of posts we first look at how race and ethnicity lead to the formation of groups that have a sense of themselves as different from the dominant group. Then we analyze patterns of inequality and intergroup relations. Finally we discuss cultural consequences, particularly in American society. This is followed by a presentation of social-scientific theories that seek to explain the phenomena of intergroup conflict and accommodation.

Race: A Social Concept

Of the millions of species of animals on earth, ours, Homo sapiens, is the most widespread. For the past 10 Millennia we have been spreading northward and southward and across the oceans to every corner of the globe, but we have not done so as a single people. Rather, throughout our history we have been divided into innumerable societies, each of which maintains its own culture, thinks of itself as "we," and looks upon all others as "they." Through all the Millennia of warfare, migration, and population growth, we have been colliding and competing and learning to cooperate. The realization that we are one great people despite our immense diversity has been slow to evolve. We persist in creating arbitrary divisions based on physical differences that are summed up in the term race.

In biology, race refers to an inbreeding population that develops distinctive physical characteristics that are hereditary. Such a population therefore has a shared genetic heritage (Graves, 2001, The Emperor's New Clothes; Marks, December, 1994. Black, White, Other. Natural History, pp. 32-35). But the choice of which physical characteristics to use in classifying people into races is arbitrary. Skin color, hair form, blood type, and facial features such as nose shape and eye folds have been used by biologists in such efforts. In fact, however, the distribution of these traits overlaps considerably among the so-called races. Human groups have exchanged their genes through mating to such an extent that any attempt to identify pure races is bound to be fruitless (Gould, 1981, The Mismeasure of Man; Graves, 2001). Thus, biologists Joseph Graves points out:

As far as distinct lineages, throughout history, we have had too much gene flow between so-called races. If sub-Saharan Africans only mated with sub-Saharan Africans and Europeans only mated with Europeans then there might be unique lineages. But that has not occurred, particularly in America. Here, because of our history of chattel slavery, individuals are still classified as black by means of the "rule of hypodescent," whereby one drop of black blood makes one black. However, there is no biological rationale for this rule. (quoted in Villarosa, January 1, 2002, A Conversation with Joseph Graves. New York Times, p. F5)

Yet doesn't common sense tell us that there are different races? Can't we see there is a Negro or black, race of people with dark skin, tightly curled hair, and broad facial features a Caucasian, or white, race of people with pale skin and ample body hair and mongoloid or Oriental race of people with yellowish or reddish skin and drop-eyelids that give their eyes a slanted look? Of course these races exist. But they are not a set of distinct populations based on biological differences. The definitions of race used in different societies emerged from the interaction of various populations over long periods of human history. The specific physical characteristics that we use to assign people to different races are arbitrary and meaningless---people from the Indian subcontinent tend to have dark skin and straight hair; Africans from Ethiopia have dark skin and narrow facial features; American blacks have skin colors ranging from extremely dark to extremely light and whites have facial features and hair forms that include those of all the others supposed races. There is no scientifically valid typology of human races; blood count is what people in a society define as meaningful. In short, race is a social concept that varies from one society to another, depending on how the people of that society feel about the importance of certain physical differences among human beings. In reality, as Edward O Wilson 1979 has written, human beings are one great breeding system through which the genes flow and mix in each generation. Because of that flux, mankind viewed over many generations shares a single human nature within which relatively minor hereditary influences recycle through ever-changing patterns, between the Sexes and cross families and entire populations p. 52.

Racism

Throughout human history, many individuals and groups have rejected the idea of a single human people. Tragic mistakes and incalculable suffering have been caused by the application of enormous ideas about race and racial purity. they are among the most extreme consequences all the attitude known as racism.

Racism is an ideology based on the belief that an observable, supposedly inherited trait, such as skin color, is a mark of inferiority that justifies discriminatory treatment of people with that trait. In their classic text on racial and cultural minorities Simpson and Yinger (1953, Racial and Cultural Identities) highlighted several beliefs that are at the heart of racism. The most common of these is the doctrine of biologically superior and inferior races (p. 55). Before World War I, for example, many of the foremost social thinkers in the Western world firmly believed that whites were genetically superior to blacks in intelligence. However, when the U. S. Army administered IQ tests to its recruits, the results showed that performance on such tests was linked to social class background rather than to race. And when investigators controlled four differences in social class among the test takers, the racial differences in IQ disappeared (Kleinberg, 1935, Race Differences).

There is much evidence that IQ tests are biased against members of minority groups and that something as complex and elusive as intelligence cannot be summarized by a single score on a test. The history of efforts to address inequalities in education shows that efforts to address inequalities in education shows that when they have access to high-quality educational programs, minority students quickly began to achieve at the same level as white students (William Kornblum, 2003, Sociology in a Changing World, 6th ed. p. 381).

The notion that members of different races have different personalities, that there are identifiable racial cultures, and that ethical standards differ from one race to another are among the other racist doctrines that have been debunked by social scientific studies over the past 70 years. But even though these doctrines have been discredited, they continue to play a major role in intergroup relations in many nations. Racist beliefs in the inferiority of populations that are erroneously thought of as separate races remain one of the major social problems of the modern world. And this tendency to denigrate socially defined racial groups extends to members of particular ethnic groups as well.

*ADDITIONAL SOURCE: SOCIOLOGY IN A CHANGING WORLD, 6TH ED., 2003, WILLIAM KORNBLUM, PP. 380-381*

end

|

Thursday, July 23, 2020

Sociological Imagination: How to Gain Wisdom about the Society in which We All Participate and for Whose Future We Are All Responsible (part 29)

That's what hip-hop is: It's sociology and English put to a beat, you know.

Inequalities of Social Class (Part B)

by

Charles Lamson

The Upper Classes

Sociologists regard the upper class as divided roughly into two subgroups: the richest and most prestigious families, who constitute the elite or "high society" and tend to be white Anglo-Saxon Protestants, and the "newly rich" families, who may be extremely wealthy but have not attained sufficient prestige to be included in the communities and associations of high society.

|

| FIGURE 1 Oil Tycoon John D. Rockefeller

At the beginning of the twentieth century, families whose wealth came from railroads and banking looked down on "upstarts" like Rockefeller (Figure 1) and Ford, whose money came from oil and automobiles. More recently, the great manufacturing families---the du Ponts (chemicals), the Rockefellers (oil), the Carnegies and Mellons (steel and coal)---have questioned the upper-class status of families like the Kennedys, whose wealth originally came from merchandising and whose Irish descent marked them off from the rich Protestant families.

Throughout much of the 20th century the number of family-owned fortunes declined as large corporations like General Motors, Boeing, and IBM gained greater economic power. But, the major family fortunes still represent billions of dollars of capital controlled by the members of immensely wealthy families, many of whom are not descended from earlier Yankee families. Other family names, such as Bill Gates of Microsoft or Michael Dell of Dell computers or even Oprah Winfrey, certainly one of the best-known and richest women in the United States, do not appear on the list because this compilation of family fortunes includes only those that have been active for more than one generation (Hacker, 1997, Money: Who Has How Much and Why).

Members of the upper class tend to create special places in which to live and relax (see Figure 3). They often maintain apartments in exclusive city neighborhoods and country estates in secluded communities. They send their children to the most expensive private schools and universities, maintain memberships in the most exclusive social clubs, and fly throughout the world to leisure resorts frequented by members of their own class (see Figure 4). Examples of these resorts and enclaves of great wealth include Vail and Aspen in Colorado, Palm Springs in California, Palm Beach in Florida, and large stretches of the New England coastline.

FIGURE 3 A Concern of the Elite

/GettyImages-1092630192-56b4a20e1ef14f888174097dd279766d.jpg)

FIGURE 4 Problem Solved

A question that sociologists continually debate is whether the upper class in America is also the society's ruling class. The question of whether great wealth also confers the ability to rule by controlling political actors (e.g., influence peddling) is open to empirical research and debate. Elite theorists like C. Wright Mills and William Domhoff argue that the upper class not only holds the controlling share of wealth and prestige, which it can pass along to its children, but also maintains a virtual monopoly over power in the United States (Zweigenhaft & Domhoff, 1998, Diversity in the Power Elite). A ruling class, Domhoff states, "is socially cohesive, has its basis in the large corporations and banks, plays a major role in shaping the social and political climate, and dominates the federal government through a variety of organizations and methods" (1983, p.1, Who rules America now?). Mills (1956, The Power Elite) attempted to show that this ruling class produces a power elite composed of its most politically active members plus high-level employees in the government and the military. The power elite, these sociologists claim, is the leadership arm of the ruling class.

Other sociologists and political scientists contend that there is no single, cohesive ruling class with an identifiable power elite that carries out its bidding. This is known as the pluralist concept (Polsby, 1980, Community Power and Political Theory; Sullivan, 1998, November-December. Defining Democracy Down. American Prospect, pp. 91-96). These researchers agree that there is a readily identifiable upper class in American society. However, its power is not exerted in a unified fashion because there are competing centers of wealth and power within the upper class; moreover, its members' viewpoints on social policy are often opposed to one another we return to the debate between the power elite and pluralist theories in a later part of this analysis.

FIGURE 5 Typical American Middle-Class Family

The Middle Classes

Unlike the upper classes in which family status establishes who is included in the highest stratum and who is not, the middle class includes far more varied combinations of wealth and prestige. While the concept is typically ambiguous in popular opinion in common language use (Dante Chinni, [May 10, 2005]. One more Social Security quibble: Who is middle class? The Christian Science Monitor), contemporary social scientists have put forth several congruent theories on the American middle class. Depending on the class model used, the middle class constitutes anywhere from 25% to 66% of households (Wikipedia).

One of the first major studies of the middle class in America was White Collar: The American Middle Classes, published in 1951 by sociologist C. Wright Mills. Later sociologists such as Dennis Gilbert of Hamilton College commonly divided the middle class into two subgroups. Constituting roughly 15% to 20% of households is the upper or professional middle class consisting of highly educated, salaried professionals and managers. Constituting roughly one-third of households is the lower-middle-class consisting mostly of semi-professionals, skilled craftsmen and lower level of management. (William Thompson and Joseph Hickey 2005. Society in Focus; Brian Williams, et al., 2005. Marriages, Families and Intimate Relationships).

So this large proportion of Americans who identify themselves as members of the middle class is by no means a homogeneous population. The middle class is often referred to as the middle classes to emphasize the existence of strata with differing income, education, and access to wealth. One group of Americans who identify themselves as members of the middle class are highly educated professionals (mentioned above). Most often they have attended graduate schools and built successful careers as engineers, lawyers, doctors, dentists, stockbrokers, or corporate managers. But their comfortable incomes, often much more than $100,000 a year, may also be derived from family-owned businesses. Members of this class typically live in the suburbs (see Figure 6).

FIGURE 6 The Suburbs

Another segment of the middle class is composed of people whose income is derived from small businesses, especially stores and community-oriented enterprises in contrast with large corporations that have offices at many locations. Often referred to as the petit bourgeoisie or independent small business owners, the members of this class may be found among the leaders of local chambers of commerce and other business associations that advocate local economic growth (Erik Olin Wright, et al., 1982, The American Class Structure. American Sociological Review, 47, 702-726; Wright, 1997, Class Counts).

The American concept of the middle class is based far more on patterns of consumption and the American dream of shared affluence than on the kinds of economic realities that Marx used to describe social classes. Americans have always believed that they could achieve individual affluence and become part of a great middle class. Thus in subjective terms the middle class is the largest single class in American society, but in cultural terms it is highly diverse because so many different lifestyles are represented within it.

The dominant image of the middle class from the end of World War II until the mid-1970s was of a Suburban population living in relatively new private homes (Scott, 1998. The United States of Suburbia). The culture of the suburban middle class was thought to be shaped by the experience of frequent changes of residence and long-distance commuting, together with status symbols like the "ranch house with its two-car garage, lawn & BBQ, and the nearby church and shopping center" (Schwartz, 1976, Images of Suburbia. In B. Schwartz, Ed., The Changing Face of the Suberbs, p. 327). The suburban middle class was said to be oriented toward family life and suspicious of the offbeat (Fava, 1956; Riesman, 1957, The Suburban Dislocation. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 314, 123-146). However, empirical research by several archaeologists, including Bennett Berger (1961, The Myth of Suburbia. Journal of Social Issues, 17, pp. 38-48), Herbert Gans (1967, 1976. The Uses of Poverty. In W. Feigelman, Ed., Sociology Full Circle, 4th ed.), and M. P. Baumgartner (1988, The Moral Order of a Suberb) has shown that suburban communities are far from homogeneous, that many people who think of themselves as members of the working class can be found in them, and that there is no easily identified middle-class suburban culture.

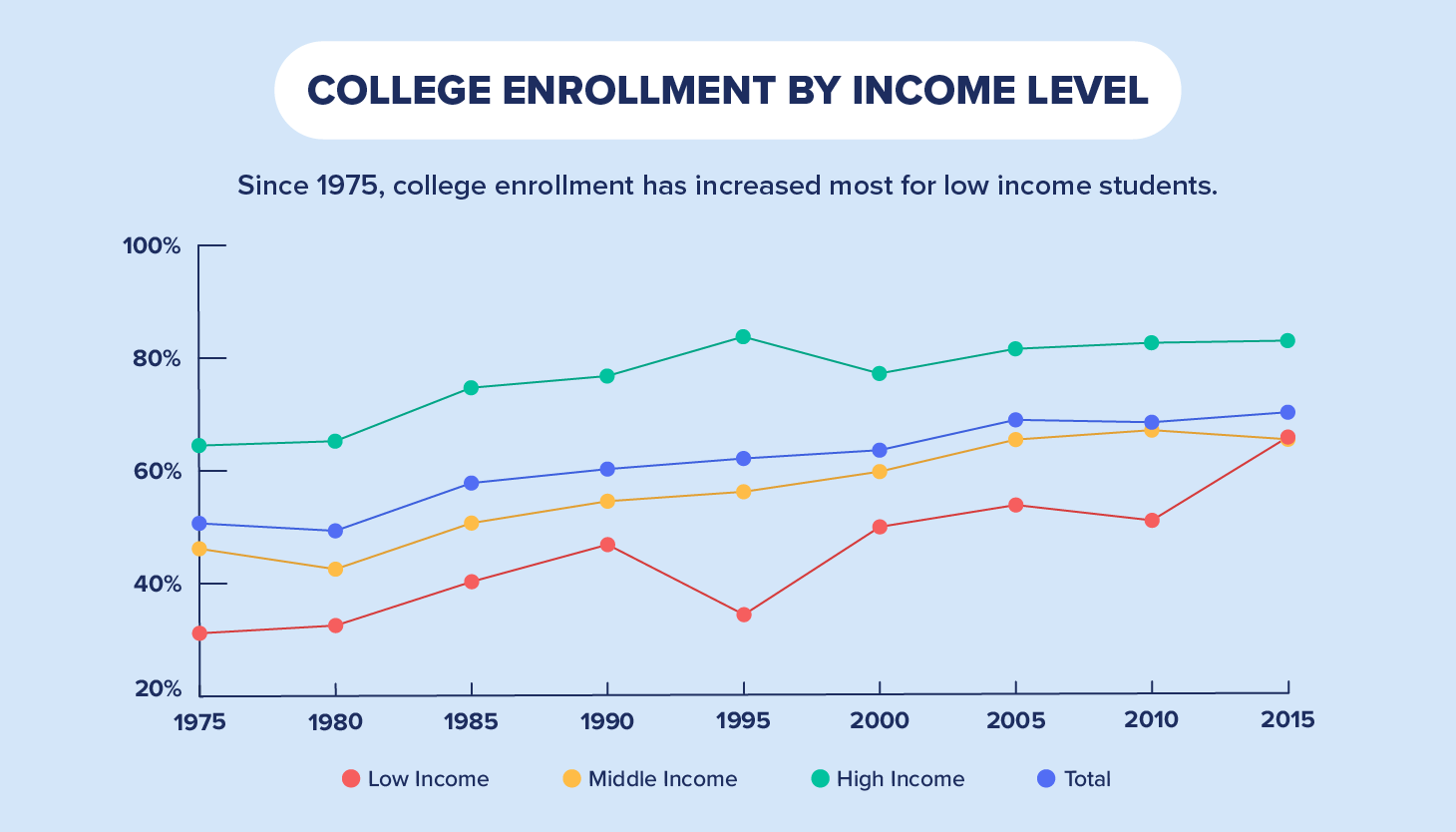

Another change in the nature of the middle class has to do with education. In the 1950s and 1960s a college diploma was often viewed as a passport to the American middle class way of life. But we will see later that, although education remains the primary route to upward mobility for people without inherited wealth, the college diploma has lost some of its power to open the door to middle-class prestige. Despite this, based on U.S. student loan debt statistics from 2015, since 1975, low-income college enrollment has had a sharp increase whereas high income (or upper-class) has appeared to level off since 2010.

FIGURE 7 (Natalie Issa, June 19, 2019, U.S. Student Loan Debt Statistics in 2019. Credit.com)

The most general points that sociologists can make about the middle class are that its members tend to be employed in non-manual occupations and that they usually have to work hard to afford the material things that are more easily acquired by the upper-middle class. Identification with the middle class is likely to be highest among teachers, middle and lower level office managers and clerical employees, government bureaucrats, and workers in the uniformed services.

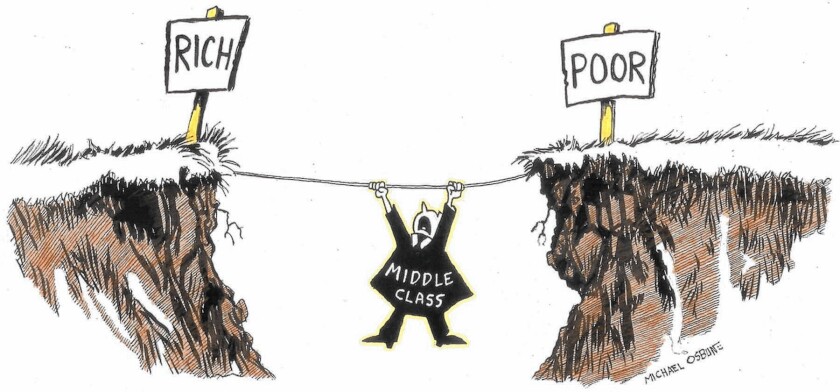

Effects of Economic Insecurity Political candidates attempt to win the support of the middle class because they recognize that large numbers of voters think of themselves as members of that class, rather than as rich or poor. But as we have seen, the idea of an all-inclusive American middle class is more of a myth than a reality for increasing numbers of working Americans. Between the extremes of poverty and wealth are, instead of a unified middle class, two increasingly distinct groups that think of themselves as middle class but face far different life chances and economic realities.

In the more secure segment of the middle class are highly skilled, highly educated professionals and managerial women and men who are doing rather well, although they increasingly experience income stagnation and must find ways to supplement their incomes. But below this segment there is a larger stratum of less-skilled and less-educated people who are experiencing ever greater economic insecurity resulting from stagnant incomes and declining living standards (see Figure 8). Appealing to this growing insecure middle-class stratum is a central goal of political leaders.

*MAIN SOURCE: SOCIOLOGY IN A CHANGING WORLD, 6TH ED., 2003, WILLIAM KORNBLUM, PP. 355-358*

end

|

Monday, July 20, 2020

Sociological Imagination: How to Gain Wisdom about the Society in which We All Participate and for Whose Future We Are All Responsible (part 28)

I see myself working in the tradition of sociology and journalism that tries to bear witness to poverty.

Inequalities of Social Class

by

Charles Lamson

Social Class and Life Chances in the United States

The rich have far more money than the poor, and they tend to have more education and a great deal more wealth, as measured by the value of homes, cars, investments, and much else. But what difference do these inequalities make in people's lives? Social scientists often answer this question by analyzing the life chances of people born into different social classes. By life chances they mean the relative likelihood that individuals will have access to the opportunities and benefits that the society values. Compare, for example, the life chances of a child born into a family in which the mother and father earn slightly more than the minimum wage by working in restaurants and supermarkets with

the life chances of a child born into the home of a police officer and a teacher, and compare both of these with the life chances of a child born into the home of a successful banker. Will these differences in the circumstances of birth affect the quality of education each child is likely to receive? Will the children's access to quality healthcare differ? Will the differences in the social class of their families influence who they are likely to marry? Will it make a difference in the likely length of their lives? The answer to all of these questions is, emphatically, yes. But being born into a given social class does not determine everything about an individual's life chances. The more a society attempts to equalize differences and life chances by improving healthcare for the poor, for example, or by creating high-quality institutions of public education---the more it reduces the impact of social class on life chances.

the life chances of a child born into the home of a police officer and a teacher, and compare both of these with the life chances of a child born into the home of a successful banker. Will these differences in the circumstances of birth affect the quality of education each child is likely to receive? Will the children's access to quality healthcare differ? Will the differences in the social class of their families influence who they are likely to marry? Will it make a difference in the likely length of their lives? The answer to all of these questions is, emphatically, yes. But being born into a given social class does not determine everything about an individual's life chances. The more a society attempts to equalize differences and life chances by improving healthcare for the poor, for example, or by creating high-quality institutions of public education---the more it reduces the impact of social class on life chances. |

Numerous social-scientific studies have shown that one's social class tells a great deal about how one will behave and the kind of life one is likely to have. Later in this section we will discuss specific social changes, but first we present some typical examples of the relationship between social class and daily life. These examples apply primarily to American society but many of the same conditions can be found in other societies as well.

Social Class in Daily Life

Class and Health A child born into a rich upper-class family is far less likely to be premature or have a low birthweight than one born into a working-class or poor family. And a baby born into a family in which the parents are working at steady jobs is far less likely to be born with a drug addiction or AIDS or fetal alcohol syndrome than a child born to parents who are unemployed and homeless. These and many other disparities contribute to what is often called "the socioeconomic status (SES) gradient in health" (Sapolsky, [1998, April]. How the Other Half Heals. Discover, 46-72).

The SES gradient in health exists in all of our world's nations and is based on a complex combination of social class and culture, but the gradient is particularly marked in the United States:

For example, in the United States the poorer you are the more likely you are to contract and succumb to heart disease, respiratory disorders, ulcers, rheumatoid disorders, psychiatric diseases, or a number of types of cancer. And this is a whopper of an effect: In some cases disease or mortality risk increases more than five-fold as you go from the wealthiest to the poorest segments of our society, with things worsening each step of the way. (Sapolsky, 1998. P. 46)

Among adults, a salaried member of the upper class who directs the activities of other employees is less likely to be exposed to toxic chemicals or to experience occupational stress and peptic ulcers than wage workers at their machines and computer terminals. These workers, in turn, are more likely to have adequate health insurance and medical care than the working poor---dishwashers, migrant laborers, temporary help, low-paid workers, and others whose wages for full-time work do not elevate them above the poverty level (Elwood, 1988, Poor Support). The working poor are the largest category of poor Americans, and like those who lack steady jobs they often depend on the local emergency rooms for medical care and report that they have neither family doctors nor health insurance. The same poor and working-class population is also more likely to smoke, consume alcohol, and be exposed to homicide and accidents while receiving less police protection than members of the classes above them.

Education Children of upper-class families are more likely to be educated in private schools than children from the middle or working classes. Sociologists have shown that education in elite private schools is a means of socializing the rich. Cookson and Persell's 1985 study of socialization Preparing for Power study of socialization in elite American prep schools found that "preppies" develop close ties to their classmates, ties that often last throughout life and become part of a network they can draw on as they rise to positions of power and wealth. The segregation of upper-class adolescence in prep schools also limits dating and marriage opportunities to members of the same class.

Although middle-class parents are more likely than rich parents to send their children to public schools, they tend to select suburban communities where the schools are known to produce successful college applicants. The public schools that serve the middle classes spend more per pupil than the schools attended by working class and poor children, and they offer a wider array of special services in such areas as music, sports, and extracurricular activities. Children in the middle and upper classes also tend to have parents who insist that they perform well in school and who can help them with their school work. Moreover, children from working-class and poor families are more likely to drop out of school than children from upper-class families.

Many other examples could be presented to illustrate the influence of social class on individuals in American society. But social class divisions also affect the society as a whole. So in the next post, we will turn, therefore, to an examination of some key characteristics of the major social classes (upper-class, middle-class, working class, and the poor) in the United States, and to some of the consequences of the different life chances experienced by these classes.

*ADDITIONAL SOURCE: SOCIOLOGY IN A CHANGING WORLD, 6TH ED., WILLIAM KORNBLUM, PP.. 353-355*

end

|

Saturday, July 18, 2020

Sociological Imagination: How to Gain Wisdom about the Society in which We All Participate and for Whose Future We Are All Responsible (part 27)

Stratification and Global Inequality (Part D)

by

by

Charles Lamson

The French Revolution: A Case Study of Power, Authority, and Stratification

Max Weber defined power as "the probability that one actor within a social relationship will be in a position to carry out his own will despite resistance" (1947, The Theory of Social and Economic Organization, p. 152). This is a very general definition; it applies equally to a mugger with a gun and to an executive vice president ordering a secretary to get coffee for a visitor. But there is a big difference between the types of power used in these examples. In the first, illegitimate power is asserted through physical coercion. In the second, the secretary may not want to obey the vice president's orders yet recognizes that they are legitimate; that is, such orders are understood by everyone in the company to be within the vice president's power. This kind of power is called authority.

|

| FIGURE 1 The French Revolution

Even when power has been translated into authority, there remains the question of how authority originates and is maintained. This is a basic question in the study of stratification. As we saw in the last post, the fact that people in lower strata accept their place in society requires that we examine not only the processes of socialization but also how power and authority are used to maintain existing relations among castes or classes.

A brief review of the causes of the French Revolution of 1789 (see Figure 1) provides a case study in the relationship between power and authority on one hand and stratification on the other. Why did the French people accept the rule of absolute monarchs for so long before they finally ended that rule in a bloody revolution? In answering this question we can apply all the aspects of stratification discussed so far in previous posts. We will begin with the feudal stratification system.

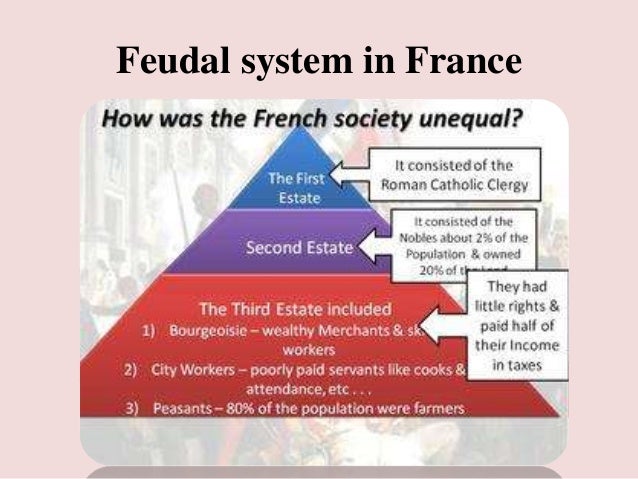

FIGURE 2 The Major Strata of Prerevolutionary French Society The major strata of French society (see Figure 2), called estates, were the nobility, the clergy, the peasantry, and the bourgeoisie (merchants, shopkeepers, and artisans). Each estate had its own institutions and culture, causing its members to feel that they were part of a unified community with its own norms and values. The estates were linked together by the time-honored norms of feudalism: vassalage and fealty. A vassal was someone who received the grants of land from a lord. In return He swore fealty, an oath of service and loyalty, to that lord. The lord, in turn swore fealty to a more powerful lord, until one reached the highest level of society, the king. In such a well-ordered and legitimate system where were the seeds of revolution? The answer lies in how power, authority, and changing modes of production combined to shake the foundations of feudal France.

In any system of stratification there are likely to be conflicts. These conflicts may be caused by the ambitions of a particular leader or group, but sometimes the characteristics of the system---and especially of the way its powerful members trying to cope with change create conflict. Both types of conflict existed in prerevolutionary France. In order to compete with the other major European powers, the king had to raise armies and send fleets abroad, both of which cost huge sums of money and required thousands of men. But the vow of fealty extended only from the king to the highest level of the nobility. The nobles, in turn, were responsible for seeing that their vassals provided more money and men. This system placed severe constraints on the king, who could not easily make direct payments on all his subjects. The king was dependent on the nobles and, through them, on the lesser lords. In return, the lesser lords often demanded more power, there by challenging the king's authority. In order to reduce the power of the lords, the king (see Figure 3) went to the clergy and the bourgeoisie for assistance.

FIGURE 3 Louis XVI: The King During the French Revolution

As the cities grew and the trading and manufacturing capacities of the bourgeoisie expanded, the king was increasingly successful at drawing on the wealth of the bourgeoisie and undermining the power of the feudal lords. The court flourished in fact. it seemed that the king's power had become absolute. But beneath the pomp and display of the court the feudal stratification system was in ruins. The weakened nobility could no longer hold the fealty of the peasants. Throughout the countryside The peasants groaned under the heavy debts imposed by their feudal masters, and they began to question the right of the nobility to tax them.

Meanwhile, in the cities and towns the rapidly growing bourgeoisie, along with the new social stratum of urban workers, clearly understood that the king's power derived from their productive activities. They felt that they were not adequately rewarded for their support. At the same time, another new stratum, the intellectuals---people who had been educated outside the church and the court---was creating a new ideology and promoting it through new institutions like the press. This new ideology---"liberty, equality, fraternity"---helped spur revolutionary social movements, but the underlying cause of the revolution was a drastic change in the stratification system, in which the new middle class of wealthy business owners (the bourgeoisie) eventually challenged the ancient aristocracy.

*MAIN SOURCE: SOCIOLOGY IN A CHANGING WORLD, 6TH ED., 2003, WILLIAM KORNBLUM, P. 318-319*

end

|

Friday, July 17, 2020

Sociological Imagination: How to Gain Wisdom about the Society in which We All Participate and for Whose Future We Are All Responsible (part 26)

I was in an interdisciplinary major - which was a new thing then - which was psychology, sociology, anthropology, and biology, which is really sort of the study of the human being.

Stratification and Global Inequality (Part C)

by

Charles Lamson

Stratification and Culture

Why do people accept their place in a stratification system, especially when they are at or near the bottom? One answer is that they have no choice; they lack not only wealth and opportunities but also the power to change their situation. But lack of power does not prevent people from rebelling against inequality. Many people also believe that their inferior place in the system is justified by their own failures or by the accident of their birth. If people who have good cause to rebel do not do so and instead support the existing stratification system, those who do wish to rebel may feel that their efforts will be fruitless.

|

FIGURE 1 A Stratification System

Another reason people accept their place in a stratification system (see Figure 1) is that the system itself is part of their culture. Through socialization we learn the cultural norms that justify our society's system of stratification. The rich learn how to act like rich people; the poor learn how to survive, and in so doing they tacitly accept being poor. Women and men learn to accept the places assigned to them, and so do the young and the old. Yet despite the powerful influence of socialization, at times large numbers of people rebel against their cultural conditioning. To understand their reasons for doing so, we need to examine the cultural foundations of stratification systems.

FIGURE 2 The American Dream

The Role of Ideology

An ideology is a system of ideas and norms that all the members of a society are expected to believe in and act on without question. Every society appears to have ideologies that justify stratification and are used to socialize new generations to believe that existing patterns of inequality are legitimate. In the United States, for example, most people embrace the ideology of the American dream (see Figure 2), the idea that in America anyone who works hard can achieve success and wealth. At the same time, we know that the odds of achieving great wealth are very low. This is one reason people love to hear stories about poor or or hard-working people of modest means whose lives are transformed by sudden lottery winnings. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the "rags-to-riches" stories of Horatio Alger were extremely popular. In Alger's first novel, Ragged Dick, the central character is a poor but honest boy who comes to the city looking for work. As he walks the streets he sees a runaway carriage; he leaps onto the horses and and stops them. In the carriage is a beautiful young woman who turns out to have a rich father. The father takes Dick into his business, where he proves his great motivation and becomes highly successful.

The people of pre-revolutionary China were also guided by ideology; they believed in the teachings of Confucius (551-479 B.C.), which emphasized the need to accept one's place in a well-ordered, highly stratified society (McNeill, 1963, The Rise of the West). Similarly, the castes of Hindu India are supported by religious ideologies. The rig-veda taught that Hindu Society was, by Divine will, divided into forecasts, of which the brahmins were the highest because they were responsible for religious ceremonies and sacrifices (Majundar, 1951, The History and Culture of the Indian People McNeil, 1963). Over time, other castes with other tasks were added to the system as the division of labor progressed and new occupations developed. Still another powerful ideology had its origins in Europe before the spread of Christianity. Tribal people in what is now France and Germany Associated their kings with Gods, and that association became stronger in the feudal era (Dodgson, 1987, The European Past).

FIGURE 3 Jesus Teaching

Religious teachings often serve as the ideologies of civilizations, explaining and justifying the stratification systems associated with them. But this relationship has not held in very every historical period or for every religious movement. Originally, for example, the teachings of Jesus (see Figure 3) opposed the stratification systems of both the Roman Empire and the Jewish people. Jesus preached a gospel of love and claimed that "The last shall be first" and "It is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter Heaven." He showed sympathy for prostitutes and outcasts such as money lenders. No wonder his teachings appealed to the poor and downtrodden and enraged the wealthy and powerful. But over many centuries Christ's teachings were incorporated into church doctrine and organization, and by the Middle Ages Christianity was the ideology underlying the stratification system of kings, lord's, merchants, and peasants. The vicar is of the church upheld that system by affirming its legitimacy in coronations and royal weddings. They also presided over the execution of heretics who challenged the system, which was viewed as divinely ordained.

In our own era the civil rights movement in the United States, the movement to end apartheid in South Africa, the struggle of the Northern Irish Catholics for independence from Britain, and other social movements often invoke the ideology of radical Christianity. "We Shall Overcome," the theme song of the civil rights movement, was borrowed from an African-American Baptist spiritual, "I Shall Overcome," and transformed into a moving song of hope and protest with religious overtones.

Stratification at the Micro Level

These relationships between religious ideologies and the stratification systems of civilizations are macro-level examples of how cultures maintain stratification systems from one generation to the next. But we can also see the connection between culture and stratification in the micro level interactions of daily life. The way we dress---whether we wear expensive designer clothes, off-the-rack apparel, or second hand clothing from the Salvation Army-- -says a great deal about our place in the stratification system. So does the way we speak, as anyone knows who has been told to get rid of a Southern or Brooklyn accent in order to "get ahead." Our efforts to possess and display status symbols---material objects or behaviors that convey prestige---are encouraged by the billion-dollar advertising industry. Many other examples could be given, but here we will concentrate on two sets of norms that reinforce stratification at the micro-level; the norms of deference and demeanor (Goldhamer & Shils, 1939, Types of Power and Status. American Journal of Sociology, 45, 171-182).

FIGURE 4 Bowing: A Common Display of Deference

Deference By deference we mean the "appreciation an individual shows of another to that other" (Goffman, 1958, Deference and Demeanor. American Anthropologist, pp. 488-489). In popular speech the word deference is often used to indicate how one person should behave in the presence of another who is of higher status. These displays of deference illustrate how our society's stratification system is experienced in everyday life. In the United States, for example, we learn to address judges as "Your Honor." In most European countries, with their histories of more rigid stratification, people who want to show deference go further and address the judge as "Your Excellence."

But deference is not a one-way process. Erving Goffman has pointed out that the act of paying deference to someone in a higher status often obligates that other person to pay some form of deference in return: "High priests all over the world seem obliged to respond to offerings of deference with an equivalent of "Bless you, my son.'" (Goffman, 1958, pp. 489). The point here is that deference is often symmetrical in that both participants defer according to their place in the stratification system. Through deferent behavior and the appropriate response, both parties affirm their acceptance of the stratification system. Intuitively we all know this. When we are stopped by a police officer we may become deferential, using the most polite forms of address ("Yes, Sir," "No, Sir," and the like) in order to avoid embarrassment. The officer, in turn, my attempt to find out our place in the stratification system and use the appropriate forms of address in speaking to us.

Demeanor Our demeanor is the way we present ourselves---our body language, dress, speech, and manners. It conveys to others how much deference or respect we believe is due us. Here again the interaction can be symmetrical. The professor must make the first move toward informality in relations with students, for instance, but among professors of equal rank there is far more symmetry. The move toward informal demeanor, such as the use of first names, can be initiated by whomever feels most comfortable in his or her status. On the other hand, asymmetry in the use of names can be used to reinforce stratification, as in an office where the secretaries are addressed by their first names but address their supervisor by his or her last name plus a title such as Mr., Dr., or Professor.

Stratification and Social Interactions These largely taken-for-granted aspects of how we carry out or construct social stratification in our social interactions can have far-reaching effects. Maya Angelou, Richard Wright, and other African American Writers describe vividly of their parents in the era of segregation. Even to lift one's eyes to admire a white woman could cause trouble for a black man in the Jim Crow regions of the United States. Failure to carry out the rules of demeanor---to twitch, to have a runny nose, to encroach on another person's space---can cause a person to be labeled deviant (see Figure 5) and to be cast out of the "acceptable" strata of society.

*MAIN SOURCE: SOCIOLOGY IN A CHANGING WORLD, 6TH ED., 2003, WILLIAM KORNBLUM, PP. 316-317*

end

|

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

-

That's what hip-hop is: It's sociology and English put to a beat, you know. Talib Kweli Inequalities of Social Class (...

-

I'm double majoring in social studies - which is sociology, anthropology, economics, and philosophy - and African-American studies. Yara...