Long-Run Costs and Output Decisions

(Part D)

by

Charles Lamson

|

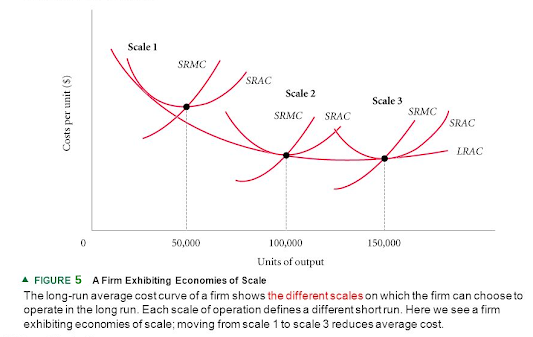

Long-Run Costs: Economies and Diseconomies of Scale

The shapes of short-run cost curves follow directly from the assumption of a fixed factor of production. As output increases beyond a certain point, the fixed factor (which we usually think of as a fixed scale of plant) causes diminishing returns to other factors and thus increasing marginal costs. In the long run, however, there is no fixed factor of production. Firms can choose any scale of production. They can double or triple output or go out of business completely. The shape of a firm's long-run average cost curve depends on how costs vary with scale of operations. For some firms, increased scale, or size, reduces costs. For others, increased scale leads to inefficiency and waste. When an increase in a firm's scale of production leads to lower average costs, we say that there are increasing returns to scale, or economies of scale. When average costs do not change with the scale of production, we say that there are constant returns to scale. Finally, when an increase in a firm's scale of production leads to higher average costs, we say that there are decreasing returns to scale, or diseconomies of scale. Because these economies of scale all are found within the individual firm, they are considered internal economies of scale. In the next post, we will talk about external economies of scale, which describe economies or diseconomies of scale on an industry-wide basis. Increasing Returns to Scale Technically, the increasing returns to scale refers to the relationship between inputs and outputs. When we say that a production function exhibits increasing returns, we mean that a given percentage of increase and inputs leads to a larger percentage of increase in the production of output. For example, if a firm doubled or tripled inputs, it would more than double or triple output. When firms can count on fixed input prices---that is, when prices of inputs do not change with output levels---increasing returns to scale also means that as output rises, average cost of production falls. The term economies of scale refers directly to this reduction in cost per unit of output that follows from larger-scale production. The Sources of Economies of Scale Most of the economies of scale that immediately come to mind are technological in nature. Automobile production, for example, would be much more costly per unit if a firm were to produce 100 cars per year by hand. Early in the twentieth century, Henry Ford introduced standardized production techniques that increased output volume, reduced costs per car, and made the automobile available to almost everyone. Some economies of scale result not from technology but from sheer size. Very large companies, for instance, can buy inputs in volume at discounted prices. Large firms may also produce some of their own inputs at considerable savings, and they can certainly save in transport costs when they ship items in bulk. Economies of scale can be seen all around us. A bus that carries 100 people between Vancouver and Seattle uses less labor, capital, and gasoline than 100 people driving 100 different automobiles. The cost per passenger (average cost) is lower on the bus. Roommates who share an apartment are taking advantage of economies of scale. Cost per person for heat, electricity, and space are lower when an apartment is shared than if each person rented a separate apartment. Example: Economies of Scale in Egg Production Nowhere are economies of scale more visible than in agriculture. Consider the following example. A few years ago a major agribusiness moved into a small Ohio town and set up a huge egg-producing operation. The new firm, Chicken Little Egg Farms Inc., is completely mechanized. Complex machines feed the chickens and collect and box the eggs. Large refrigerated trucks transport the eggs all over the state daily. In the same town, small farmers still own fewer than 200 chickens. These farmers collect the eggs, feed the chickens, clean the coops by hand, and deliver the eggs to country markets. Table 5 presents some hypothetical cost data for Homer Jones's small operation and for Chicken Little Inc. Jones has his operation working well. He has several hundred chickens and spends about 15 hours per week feeding, collecting, delivering, and so forth. In the rest of his time he raises soybeans. We can value Jones's time at $8 per hour, because that is the wage he could earn working at a local manufacturing plant. When we add up all Jones's costs, including a rough estimate of the land and capital costs attributable to egg production, we arrive at $177 per week. Total production on the Jones Farm runs about 200 dozen, or 2,400, eggs per week, which means that Jones's average cost comes out to $0.074 per egg. The costs of Chicken Little Inc. are much higher in total; weekly costs run over $30,000. A much higher percentage of costs are capital costs---the firm uses lots of sophisticated machinery that cost millions to put in place. Total output is 1.6 million eggs per week, and the product is shipped all over the Midwest. The comparatively huge scale of plant drives average production costs all the way down to $0.019 per egg. While these numbers are hypothetical, you can see why small farmers in the United States are finding it difficult to compete with large-scale agribusiness concerns that can realize significant economies of scale. Graphic Presentation A firm's long-run average cost curve (LRAC) shows the different scales on which it can choose to operate in the long run. In other words, a firm's LRAC curve traces out the position of all possible short-run curves, each corresponding to a different scale. At any time, the existing scale of plant determines the position and shape of the firm's short-run cost curves, but the firm must consider in its long run strategic planning whether to build a plant of a different scale. The long-run average cost curve simply shows the positions of the different sets of short-run curves among which the firm must choose. The long-run average cost curve is the "envelope" of a series of short-run curves; it "wraps around" the set of all possible short-run curves like an envelope. Figure 5 shows short-run and long-run average cost curves for a firm that realizes economies of scale up to about 100,000 units of production and roughly constant returns to scale after that. The diagram shows three potential scales of operation, each with its own set of short-run cost curves. Each point on the LRAC curve represents the minimum cost at which the associated output level can be produced. Once the firm chooses a scale on which to produce, it becomes locked into one set of cost curves in the short run. If the firm were to settle on scale 1, it would not realize the major cost advantages of producing on a larger scale. By roughly doubling its scale of operations from 50,000 to 100,000 units (scale 2), the firm reduces average cost per unit significantly. Figure 5 shows that at every moment firms face two different cost constraints. In the long run, firms can change their scale of operation, and cost may be different as a result. However, at any given moment, a particular scale of operation exists, constraining the firm's capacity to produce in the short run. That is why we see both short- and long-run curves in the same diagram. *CASE & FAIR, 2004, PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS, 7TH ED., PP. 180-184* end |

No comments:

Post a Comment