I call crony capitalism, where you take money from successful small businesses, spend it in Washington on favored industries, on favored individuals, picking winners and losers in the economy, that's not pro-growth economics. That's not entrepreneurial economics. That's not helping small businesses. That's cronyism, that's corporate welfare.

Household Behavior and Consumer Choice

(Part E)

by

Charles Lamson

Household Choice in Input Markets

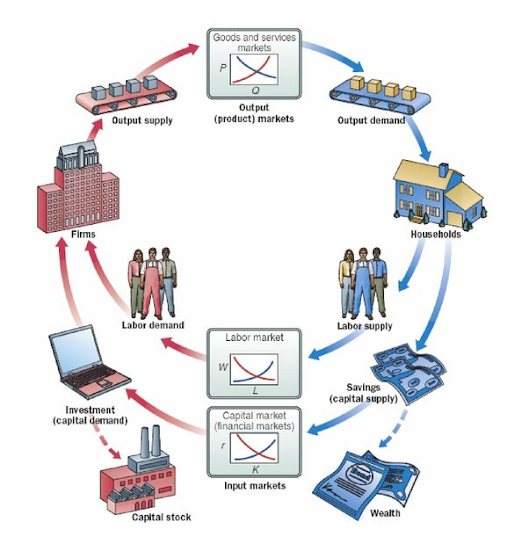

So far, we have focused on the decision-making process that lies behind output demand curves. Households with limited incomes allocate those incomes across various combinations of goods and services that are available and affordable. In looking at the factors affecting choices in the output market, we assumed that the income was fixed, or given. We noted at the outset, however, that income is in fact partially determined by choices that households make in input markets (look at Figure 1). We now turn to a brief discussion of the two decisions households make an input Market cooler the labor Supply decision and the saving decision. The Labor Supply Decision Most income in the United States is wage and salary income paid in compensation for labor. Household members supply labor in exchange for wages or salaries. As in output markets, households face constrained choices in input markets. They must decide:

In essence, household members must decide how much labor to supply. The choices they make are affected by:

As with decisions in output markets, the labor supply decision involves a set of trade-offs. There are basically two alternatives to working for a wage: (1) not working, and (2) unpaid work. If I do not work, I sacrifice income for the benefits of staying at home and reading, watching TV, swimming, or sleeping. Another option is to work, but not for a money wage. In this case, I sacrifice money income for the benefits of growing my own food, bringing up my children, or taking care of my house. As with the trade-offs in the output markets, my final choice depends on how I value the alternatives available. If I work, I earn a wage that I can use to buy things. Thus, the trade-off is between the value of the goods and services I can buy with the wages I earn versus the value of things I can produce--- homegrown food, manageable children, clean clothes, and so on---or the value I place on leisure. This choice is Illustrated in Figure 9. In general, then: The wage rate can be thought of as the price or the opportunity cost of the benefits of either unpaid work or leisure. The Price of Leisure When we add leisure to the picture, we do so with one important distinction. Trading off one good for another involves buying less of one and more of another, so households simply reallocate money from one good to the other. "Buying" more leisure, however, means reallocating time between work and non-work activities. For each hour of leisure that I decide to consume, I give up one hour's wages. Thus the wage rate is the price of leisure. Conditions in the labor market determine the budget constraints and final opportunity sets that face households. The availability of jobs and these job wage rates determined the final combinations of goods and services that a household can afford. The final choice within these constraints depends on the unique tastes and preferences of each household. Different people place more or less value on leisure but everyone needs to put food on the table. Income and Substitution Effect of a Wage Change A labor supply curve shows the quantity of labor supplied at different wage rates. The shape of the labor supply curve depends on how households react to changes in the wage rate. Consider an increase in wages. First, an increase in wages makes households better off. If they work the same number of hours---that is, if they supply the same amount of labor they will earn higher incomes and be able to buy more goods and services. They can also buy more leisure. If Leisure is a normal good---that is, a good for which demand increases as income increases and increase in income will lead to a higher demand for leisure and a lower labor supply. This is the income effect of a wage increase. However, there is also a potential substitution effect of a wage increase. A higher wage rate means that leisure is more expensive. If you think of the wage rate as the price of leisure, each individual hour of leisure consumed at a higher wage costs more in forgone wages. As a result, we would expect households to substitute other goods for leisure. This means working more, or a lower quantity demanded of leisure and a higher quantity supplied of labor. Note that in the labor market the income and substitution effects work in opposite directions when leisure is a normal good. The income effect of a wage increase implies buying more leisure and working less; the substitution effect implies buying less leisure and working more. Whether households will supply more labor overall or less labor overall when wages rise depends on the relative strengths of both the income and the substitution effect. If the substitution effect is greater than the income effect, the wage increase will increase labor supply. This suggests that the labor supply curve slopes upward, or has a positive slope, like the one in Figure 10(a). If the income effect outweighs the substitution effect, however, a higher wage will lead to added consumption of leisure, and labor supply will decrease, this implies that the labor supply curve "bends back," as the one in Figure 10(b). During the early years of the Industrial Revolution in the late eighteenth-century Great Britain, the textile industry operated under what was called the "putting out" system. Spinning and weaving were done in small cottages to supplement the family farm income hence the term "cottage industry." During that period, wages and household incomes rose considerably. Some economic historians claim that this higher income actually led many households to take more leisure and work fewer hours; the empirical evidence suggests a backward bending labor supply curve. Just as income and substitution effects helped us understand household choices in output markets, they now help understand household choices in input markets. The point here is simple: When leisure is added to the choice set, the line between input and output market decisions becomes blurred. In fact, households decide simultaneously how much of each good to consume and how much leisure to consume. *MAIN SOURCE: CASE & FAIR, 2004, PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS, 7TH ED., PP. 115-118* end |

No comments:

Post a Comment