Mission Statement

Sunday, February 28, 2021

Saturday, February 27, 2021

No Such Thing as a Free Lunch: Principles of Economics (Part 24)

Design is a way of life, a point of view. It involves the whole complex of visual communications: talent, creative ability, manual skill, and technical knowledge. Aesthetics and economics, technology and psychology are intrinsically related to the process.

Demand and Supply Applications and Elasticity

(Part G)

by

Charles Lamson

|

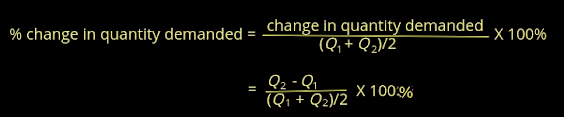

The Determinants of Demand Elasticity

Elasticity of demand is a way of measuring the responsiveness of consumers' demand to changes in price. As a measure of behavior, it can be applied to individual households or to market demand as a whole. Some people love peaches and would hate to give them up. Their demand for peaches is therefore inelastic. However, not everyone is crazy about peaches, and, in fact, the market demand for peaches is relatively elastic. This may not be the best example, but the point is that because no two people have exactly the same preferences, reactions to price changes will be different for different people, and this makes generalizations hazardous. Nonetheless, a few principles do seem to hold. Availability of Substitutes Perhaps the most obvious factor affecting demand elasticity is the availability of substitutes. Consider a number of farm stands lined up along a country road. If every stand sells fresh corn of roughly the same quality, Mom's a Green Thumb will find it very difficult to charge a price much higher than the competition charges, because a nearly perfect substitute is available just down the road. The demand for Mom's corn is thus likely to be very elastic: an increase in price will lead to a rapid decline in the quantity demanded of Mom's corn In Table 1 from Part 22 of this analysis and reintroduced below, we considered two products that have no readily available substitutes, local telephone service and insulin for diabetics. There are many others. Demand for these products is likely to be quite inelastic. The Importance of Being Unimportant When an item represents a relatively small part of our total budget, we tend to pay little attention to its price. For example, if I pick up a pack of mints once in awhile, I might not notice an increase in price from $0.25 to $0.35. Yet this is a 40 percent increase in price (33.3 percent using the midpoint formula introduced in last post and reintroduced below). In cases such as these, we are not likely to respond very much to changes in price, and demand is likely to be inelastic. Midpoint Formula The Time Dimension When the OPEC nations cut output and succeeded in pushing up the price of crude oil in the early 1970s, few substitutes were immediately available. Demand was relatively inelastic, and prices rose substantially. During the last thirty years, however, there has been some adjustment to higher oil prices. Automobiles manufactured today get on average more miles per gallon, and some drivers have cut down on their driving. Millions have insulated their homes, most have turned down their thermostats, and some have explored alternative energy sources. All of this illustrates a very important point: The elasticity of demand in the short run may be very different from the elasticity of demand in the long run. In the longer run, demand is likely to become more elastic, or responsive, simply because households make adjustments over time and producers develop substitute goods. Other Important Elasticities So far we have been discussing price elasticity of demand, which measures the responsiveness of quantity demanded to changes in price. However, as we noted earlier, elasticity is a perfectly General concept. If B causes a change in a and we can measure the change in both, we can calculate the elasticity play with respect to the. Let us look briefly at 3 other important types of elasticity. Income Elasticity of Demand Income elasticity of demand, which measures the responsiveness of demand to changes in income, is defined as: Measuring income elasticity is important for many reasons. Government policymakers spend a great deal of time and money weighing the relative merits of different policies. During the 1970s, for example, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) conducted a huge experiment in four cities to estimate the income elasticity of housing demand. In this "housing allowance demand experiment," low-income families received housing vouchers over an extended period of time, and researchers watched their housing consumption for several years. Most estimates, including the ones from the HUD study, put the income elasticity of housing demand between .5 and .8. That is, a 10 percent increase in income can be expected to raise the quantity of housing demanded by a household by 5 percent to 8 percent. Cross-Price Elasticity of Demand Cross-price elasticity of demand, which measures the response of quantity of one good demanded to a change in the price of another good, is defined as: Like income elasticity, cross-price elasticity can be either positive or negative. A positive cross-price elasticity indicates that an increase in the price of X causes the demand for Y to rise. This implies that the goods are substitutes. If cross-price elasticity turns out to be negative, an increase in the price of X causes a decrease in the demand for Y. This implies that the goods are complements (goods whose appeal increases with the popularity of their complement). Elasticity of Supply Elasticity of supply, which measures the response of quantity of a good supplied to a change in price of that good, is defined as: In output markets, the elasticity of supply is likely to be a positive number---that is, a higher price leads to an increase in the quantity supplied, ceteris paribus. In input markets, however, some interesting problems arise. Perhaps the most studied elasticity of all is the elasticity of labor supply, which measures the response of labor supply to a change in the price of labor. Economists have examined household labor supply responses to such government programs as welfare, Social Security, income tax system, need-based student aid, and unemployment insurance, among others. In simple terms, the elasticity of Labor Supply is defined as: It seems reasonable at first glance to assume that an increase in wages increases the quantity of labor supplied. That would imply an upward-sloping supply curve and a positive labor supply elasticity, but this is not necessarily so. An increase in wages makes workers better off: They can work the same amount and have higher incomes. One of the things that they might like to "buy" with that higher income is more leisure time. "Buying" leisure simply means working fewer hours, and the "price" of leisure is the lost wages. Thus it is quite possible that an increase in wages to some groups and above some level will lead to a reduction in the quantity of labor supplied. *MAIN SOURCE: CASE & FAIR, 2004, PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS, 7TH ED., PP. 94-96* end |

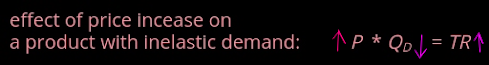

Friday, February 26, 2021

No Such Thing as a Free Lunch: Principles of Economics (Part 23)

Demand and Supply Applications and Elasticity

(Part F)

by

Charles Lamson

Calculating Elasticities

Elasticities must be calculated cautiously. Return for a moment to the demand curves in Figure 10 from last post and reintroduced below. The fact that these two identical demand curves have dramatically different slopes should be enough to convince you that slope is a poor measure of responsiveness. The concept of elasticity circumvents the measurement problem posed by the graphs in Figure 10 by converting the changes in price and quantity into percentage changes. Recall also from last post that elasticity of demand is the percentage change in quantity demanded divided by the percentage change in price. To calculate percentage change in quantity demanded using the initial value as the base, the following formula is used: In other words, decreasing price from $3 to $2 is a 33.3% decline. Elasticity Is a Ratio of Percentages Once all the changes in quantity demanded and price have been converted into percentages, calculating elasticity is a matter of simple division. Recall the formal definition of elasticity: If demand is elastic, the ratio of percentage change in quantity demanded to percentage change in price will have an absolute value greater than one. If demand is inelastic, the ratio will have an absolute value between 0 and 1. If the two percentages are exactly equal, so that a given percentage change in price causes an equal percentage change in quantity demanded, elasticity is equal to -1; this is unitary elasticity. Substituting the preceding percentages, we see that a 33.3% decrease in price leads to a 100% increase in quantity demanded; thus: According to these calculations, the demand for steak is elastic. Thus, an increase from 5 pounds to 10 pounds is a 100% increase (because the initial value used for the base is 5), but a decrease from 10 pounds to 5 pounds is only a 50 percent decrease (because the initial value used for the base is 10). This does not make much sense because in both cases we are calculating elasticity on the same interval on the demand curve. Changing the "direction" of the calculation should not change the elasticity. Thus, the midpoint formula for calculating the percentage change in quantity demanded becomes: Substituting the numbers from the original Figure 10 (a), we get: Substituting the numbers from the original Figure 10(a) yields: We can thus say that a change from a quantity of 5 to a quantity of 10 is a +66.7% change using the midpoint formula, and the change in price from $3 to $2 is a -40 percent change using the midpoint formula. Using these percentages to calculate elasticity yields: Using the midpoint formula in this case gives all over demand elasticity, but the demand remains elastic because the percentage change in quantity demanded is still greater than the percentage change in price and absolute size. Elasticity Changes along a Straight Line Demand Curve An interesting and important point is that elasticity changes from point to point along a demand curve even if the slope of that demand curve does not change---that is, even along a straight line demand curve. Indeed, the differences in an elasticity along a demand curve can be quite large. Consider the demand schedule shown in Table 3 and the demand curve in Figure 12. Herb works about 22 days per month in a downtown San Francisco office tower. On the top floor of the building is a nice dining room. If lunch in the dining room costs $10, Herb would eat there only twice a month. If the price of lunch falls to $9, he would eat there four times a month. (Herb would bring his lunch to work on other days.) If lunch were only a dollar, he would eat there 20 times a month. Table 3 Let us calculate price elasticity of demand between points A and B on the demand curve in Figure 12. Moving from A to B, the price of a lunch drops from $10 to $9 (a decrease of $1) and the number of dining room lunches that Herb eats per month increases from 2 to 4 (an increase of 2). We will use the midpoint approach. First, we calculate the percentage change in quantity demanded: Substituting the numbers from Figure 12, we get: Next, we calculate the percentage change in price: By substituting the numbers from figure 12: Finally we calculate elasticity by dividing: The percentage change in quantity demanded is 6.4 times larger than the percentage change in price. In other words, Herb's demand between points A and B is quite responsive; his demand between points A and B is elastic. Now consider a different movement along the same demand curve in Figure 12. Moving from point C to point D, the graph indicates that at a price of $3, Herb eats in the office dining room 16 times per month. If the price drops to $2, he eats there 18 times per month. These changes expressed in numerical terms are exactly the same as the price and quantity changes between point A and B in the figure---price falls $1, and quantity demanded increases by two meals. Expressed in percentage terms, however, these changes are very different. Elasticity and Total Revenue We have seen in Part 18 of this analysis that OPEC increased its revenues in the 1970s by restricting supply and pushing up the market price of crude oil. It was also argued in Part 22 that a similar strategy of OBEC would probably fail. Why? The quantity of oil demanded is not as responsive to a change in price as is the quantity of bananas demanded. In other words, the demand for oil is more inelastic than is the demand for bananas. We can now use the more formal definition of elasticity to make more precise the argument of why OPEC would succeed and OBEC would fail. In any market, P * Q is total revenue (TR) received by producers: OPEC's total revenue is the price per barrel of oil (P) times the number of barrels its participant countries sell (Q). To banana producers, total revenue is the price per bunch times the number of bunches sold. Because total revenue is the product of P and Q, whether TR rises or falls in response to a price increase depends on which is bigger, the percentage increase in price or the percentage decrease in quantity demanded. If the percentage decrease in quantity demanded is smaller than the percentage increase in price, total revenue will rise. This occurs when demand is inelastic. In this case, the percentage price rise simply outweighs the percentage quantity declined, and P * Q = (TR) rises: If, however, the percentage decline in quantity demanded following a price increase is larger than the percentage increase in price, total revenue will fall. This occurs when demand is elastic. The percentage price increase is outweighed by the percentage quantity decline: The opposite is true for a price cut, when demand is elastic, I'll cut in price increases total revenues: When demand is inelastic, a cut in price reduces total revenues: Review the logic of these equations to make sure you understand the reasoning thoroughly. With this knowledge, we can now easily see why the OPEC cartel was so effective. The demand for oil is inelastic. Restricting the quantity of oil available led to a huge increase in the price of oil---the percentage of increase was larger in absolute value than the percentage decrease in the quantity of oil demanded. Hence, OPEC's total revenue went up. In contrast, an OBEC cartel would not be effective because the demand for bananas is elastic. A small increase in the price of bananas results in a large decrease in the quantity of bananas demanded and thus causes total revenues to fall. *MAIN SOURCE: CASE & FAIR, 2004, PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS, 7TH ED., PP. 88-93* end |

-

That's what hip-hop is: It's sociology and English put to a beat, you know. Talib Kweli Inequalities of Social Class (...

-

I'm double majoring in social studies - which is sociology, anthropology, economics, and philosophy - and African-American studies. Yara...