Doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results when, in fact, the results never change, is one definition of insanity. That goes for economics, too.

The Economic Problem: Scarcity and Choice

(Part D)

by

Charles Lamson

|

Comparative Advantage and the Gains from Trade

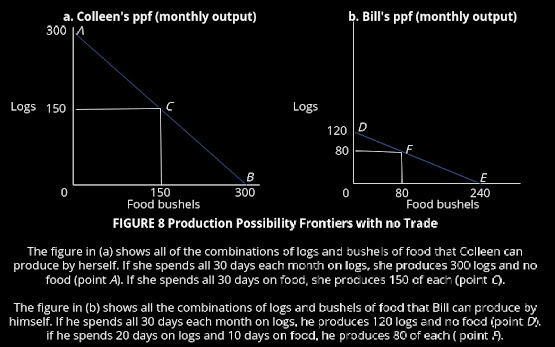

You will recall from last post that the production possibility frontier (ppf) is a simple graphic device that illustrates the principles of constrained choice, opportunity costs, and scarcity. This post shows how the ppf can also be used to show the benefits from specialization and trade. Recall the story earlier in Part 5 of this analysis of Colleen and Bill on a desert island. In that example we assumed that that Colleen could cut 10 logs per day or she could gather 10 bushels of food per day. To construct her production possibility frontier (see Figure 8(a)), we start with the end points. If she were to devote an entire month (30 days) to log production, she could cut 300 logs---10 logs per day * 30 days. Similarly, if she were to devote an entire month to food gathering, she could produce 300 bushels. If she chose to split her time evenly (15 days to logs and 15 days to food), she would have 150 bushels and 150 logs. Her production possibilities are illustrated by the straight line between A and B. The ppf illustrates the trade-off that she faces between logs and food: By reducing her time spent on food gathering, she is able to devote more time to logs, and for every 10 bushels of food that she gives up she gets 10 logs. In Figure 8(b) , we construct Bill's ppf. Recall that Bill can produce 8 bushels of food per day, but he can only cut 4 logs. Again, starting with the end points, if Bill devoted all his time to food production, he could produce 240 bushels---8 bushels of food per day * 30 days. Similarly, if he were to devote the entire 30 days to log cutting, he could cut 120 logs---4 logs per day * 30 days. By splitting his time with 20 days spent on log cutting and 10 days spent gathering food, Bill could produce 80 logs and 80 bushels of food. His production possibilities are illustrated by the straight line between D and E. By shifting his resources and time from logs to food, he gets two bushels for every log. Figures 8(a) and 8(b) illustrate the maximum amounts of food and logs that Bill and Colleen can produce acting independently with no specialization or trade, which is 230 logs and 230 bushels. Now again recall from Part 5 of this analysis that according to David Ricardo's theory of comparative advantage (A producer has a comparative advantage over another in the production of a good or service if it can produce the good or service at a lower opportunity cost.), specialization and free trade will benefit all trading parties, even when some are "absolutely" (A producer has an absolute advantage over another in the production of a good or service if it can produce the good or service using fewer resources, including its time.) more efficient producers than others. Bearing all that in mind, let's now have Colleen and Bill specialize in producing the good in which he or she has a comparative advantage. Back in Figure 2 (from Part 5 and reintroduced below) we showed that if Bill devotes all his time to food production producing 240 bushels (30 days * 8 bushels per day) and Colleen devotes the vast majority of her time to cutting logs (27 days) and just a few days to gathering food (3 days), their combined a total would be 270 logs and 270 bushels of food. Colleen would produce 270 logs and 30 bushels of food to go with Bill's 240 bushels of food. FIGURE 2 Comparative Advantage and the Gains from Trade In this figure, (a) shows the number of logs and bushels of food that Colleen and Bill can produce for every day spent at the task; (b) shows how much output they could produce in a month assuming they wanted an equal number of logs and bushels. Colleen would split her time 50/50, devoting 15 days to each task and achieving total output of 150 logs and 150 bushels of food. Bill would spend 20 days on cutting wood and 10 days on gathering food. As shown in (c) and (d), by specializing and trading, both Colleen and Bill would be better off. Going from (c) to (d), Colleen trades 100 logs to Bill in exchange for 140 bushels of food. Finally, we arrange a trade, and the result is shown in Figures 9(a) and 9(b). Bill trades 140 bushels of food to Colleen for 100 logs and he ends up with 100 logs and 100 bushels of food, 20 more of each than he would have had before the specialization and trade. Colleen ends up with 170 logs and 170 bushels, again 20 more of each than she would have had before the specialization and trade. Both are better off. Both move out beyond their individual production possibilities. Although it exists only as an abstraction, the ppf illustrates a number of very important concepts that we shall use throughout the rest of this analysis: scarcity, unemployment, inefficiency, opportunity cost, the law of increasing opportunity cost, economic growth, and the gains from trade. The Economic Problem Recall the three basic questions facing all economic systems: (1) What gets produced? (2) How is it produced? And (3) Who gets it? When Bill was alone on the island, the mechanism for answering these questions was simple: He thought about his own wants and preferences, looked at the constraints imposed by the resources of the island and his own skills and time, and made his decisions. As he set about his work, he allocated available resources quite simply, more or less by dividing up his available time. Distribution of the output was irrelevant because Bill was the society, he got it all. Introducing even one more person into the economy---in this case, Colleen---changed all that. With Colleen on the island, resource allocation involves deciding not only how each person spends time but also who does what; and now there are two sets of wants and preferences. If Bill and Colleen go off on their own and form two completely separate self-sufficient economies, there will be lost potential. Two people can do many more things together that one person can do alone. They may use their comparative advantages and different skills to specialize. Cooperation and coordination may give rise to gains that would otherwise not be possible. When a society consists of millions of people, the problem of coordination and cooperation becomes enormous, but so does the potential for gain. In large, complex economies, specialization can go wild, with people working in jobs as different in their detail as an impressionist painting is from a blank page. The range of products available in a modern industrial society is beyond anything that could have been imagined a hundred years ago, and so is the range of jobs. The amount of coordination and cooperation in a modern industrial society is almost impossible to imagine. Yet something seems to drive economic systems, if sometimes clumsily and inefficiently, toward producing the things that people want. Given scarce resources, how exactly do large, complex societies go about answering the three basic economic questions? This is the economic problem, and this is what this analysis is about. *MAIN SOURCE: CASE & FAIR, 2004, PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS, 7TH ED., PP. 33-36* end |

No comments:

Post a Comment