The breakdown of the black community, in order to maintain slavery, began with the breakdown of the black family. Men and women were not legally allowed to get married because you couldn't have that kind of love. It might get in the way of the economics of slavery. Your children could be taken from you and literally sold down the river.

Demand and Supply Applications and Elasticity (Part D)

by

Charles Lamson

|

Supply and Demand and Market Efficiency

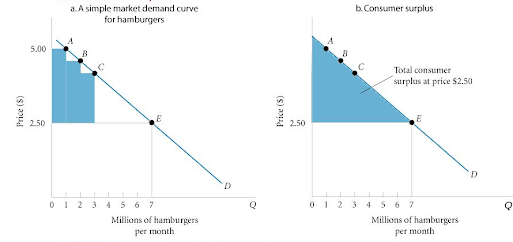

Clearly, supply and demand curves help explain the way that markets and market prices work to allocate scarce resources. Recall from Part 2 of this analysis that when we try to understand how the system works, we are doing positive economics (the branch of economics that concerns the description, quantification, and explanation of economic phenomena). Supply and demand curves can also be used to illustrate the idea of market efficiency, an important aspect of normative economics (a part of economics whose objective is fairness or what the outcome of the economy or goals of public policy ought to be). To understand the ideas you first must understand the concepts of consumer and producer surplus. Consumer Surplus The argument, made several times already in this analysis, that the market forces us to reveal a great deal about our personal preferences is an extremely important one, and it bears repeating at least once more here. If you are free to choose within the constraints imposed by prices and your income, and you decide to buy (say) a hamburger for $2.50, you have "revealed" that a hamburger is worth at least $2.50 to you. A simple market demand curve such as the one in Figure 6(a) illustrates this point quite clearly. At the current market price of $2.50, consumers will purchase seven million hamburgers per month. There is only one price in the market, and the demand curve tells us how many hamburgers households would buy if they could purchase all they wanted at the posted price of $2.50. Anyone who values a hamburger at $2.50 or more will buy it. Anyone who does not value it that highly will not. Some people, however, value hamburgers at more than $2.50. As Figure 6(a) shows, even if the price were $5, consumers would still buy 1 million hamburgers. If these people were able to buy the good at a price of $2.50, they would earn a consumer surplus. Consumer surplus is the difference between the maximum amount a person is willing to pay for a good and its current market price. The consumer surplus earned by the people willing to pay $5 for a hamburger is approximately equal to the shaded area between point A and the price, $2.50. The second million hamburgers in Figure 6(a) are valued at more than the market price as well, although the consumer surplus gained is slightly less. Point B on the market demand curve shows the maximum amount that consumers would be willing to pay for the second million hamburgers. The consumer surplus earned by these people is equal to the shaded area between B and the price, $2.50. Similarly, for the third million hamburgers, maximum willingness to pay is given by Point C; consumer surplus is a bit lower than it is at points A and B, but it is still significant. The total value of the consumer surplus suggested by the data in Figure 6(a) is roughly equal to the area of the shaded triangle in Figure 6(b). To understand why this is so, think about offering hamburgers to consumers at successively lower prices. If the good were actually sold for $2.50, those near point A on the demand curve would get a large surplus; those at point B would get a smaller surplus. Those at point E would get no surplus. Producer Surplus Similarly, the supply curve in a market shows the amount that firms willingly produce and supply to the market at various prices. Presumably it is because the price is sufficient to cover the costs or the opportunity costs of production and give producers enough profit to keep them in business. When speaking of cost of production we include everything that a producer must give up in order to produce a good. A simple market supply curve like the one in figure 7(a) illustrates this point quite clearly. At the current market price of $2.50, producers will produce and sell 7 million hamburgers. There is only one price in the market, and the supply curve tells us the quantity supplied at each price. Notice, however, that if the price were just $0.75, while production would be much lower---most producers would be out of business at that price---a few producers would actually be supplying burgers. In fact, producers would supply about 1 million burgers to the market. These firms must have lower costs: they are either more efficient, have access to raw beef at a lower price, or perhaps they can hire low-wage labor. If these efficient, low-cost producers are able to charge $2.50 for each hamburger, they are earning what is called a producer surplus. Producer surplus is the difference between the current price and the full cost of production for the firm. The first 1 million hamburgers would generate a producer surplus of $2.50 minus $0.75 or $1.75 per hamburger: a total of $1.75 million. The second million hamburgers would also generate a producer surplus because the price of $2.50 exceeds the producers total cost of producing these hamburgers, which is above $0.75 but much less than $2.50. The total value of the producer surplus received by producers of hamburger at a price of $2.50 per burger is roughly equal to the shaded triangle in Figure 7(b). Those producers just able to make a profit producing burgers will be near point E on the supply curve and will earn very little in the way of surplus. Competitive Markets Maximize the Sum of Producer and Consumer Surplus In the preceding example, the quantity of hamburgers supplied and the quantity of hamburgers demanded are equal. Figure 8 shows the total net benefits to consumers and producers resulting from the production of seven million hamburgers. Consumers receive benefits, in excess of the price they pay, equal to the blue shaded area between the demand curve and the price line at $2.50; the area is equal to the amount of consumer surplus being earned. Producers receive compensation, in excess of costs, equal to the red shaded area between the supply curve and the price line at $2.50; the area is equal to the amount of producer surplus being earned. Now consider the result to consumers and producers if production were to be reduced to 4 million burgers. Look carefully at figure 9(a). at 4 million burgers, consumers are willing to pay $3.75 for hamburgers and there are firms whose cost makes it worthwhile to supply at a price as low as $1.50, yet something is stopping production at 4 million. The result is a loss of both consumer and producer surplus. You can see in figure 9(a) that if production where expanded from 4 million to 7 million the market would yield more consumer surplus and more producer surplus. The total loss of producer and consumer surplus from under production or, as we will see you shortly, also from overproduction, is referred to as deadweight loss. In Figure 9(a) the deadweight loss is equal to the area of triangle ABC shaded in yellow. Figure 9(b) illustrates how a deadweight loss of both producer and consumer surplus can result from overproduction as well. For every hamburger produced above 7 million, consumers are willing to pay less than the cost of production. The cost of the resources needed to produce hamburgers above 7 million exceed the benefits to consumers resulting in a net loss of a producer and consumer surplus equal to the yellow shaded area ABC. Potential Causes of Deadweight Loss from Under- and Over-Production Most of the next few several posts will discuss perfectly competitive markets in which prices are determined by the free interaction of supply and demand. As you will see, when supply and demand interact freely, competitive markets produce what people want at least cost, that is, they are efficient. Beginning in even later parts of this analysis, however, we will begin to relax assumptions, and we will discover a number of naturally occurring sources of market failure. Monopoly power gives firms the incentive to underproduce and overprice, taxes and subsidies may distort consumer choices, external costs such as pollution and congestion may lead to over- or under-production of some goods, and artificial price floors and price ceilings may have the same effects. *MAIN SOURCE: CASE & FAIR, 2004, PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS, 7TH ED., PP. 80-83* end |

No comments:

Post a Comment