International Financial Management

(Part E)

by

Charles Lamson

|

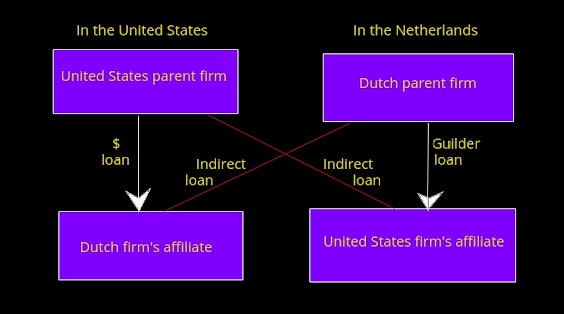

Financing International Business Operations

When the parties to an international transaction are well known to each other and the countries involved are politically stable, sales are generally made on credit, as is customary in domestic business operations. However, if a foreign importer is relatively new or the political environment is volatile, or both, the possibility of nonpayment by the importer is worrisome for the exporter. To reduce the risk of nonpayment, an exporter may request that the importer furnish a letter of credit. The importer's bank normally issues the letter of credit, in which the bank promises to subsequently pay the money for the merchandise. For example, assume Archer Daniels Midland (ADM) is negotiating with a South Korean trading company to export soybean meal. The two parties agree on price, method of shipment, timing of shipment, destination point, and the like. Once the basic terms of sale have been agreed to, the South Korean trading company (importer) applies for a letter of credit from its commercial bank in Seoul. The Korean bank, if it so desires, issues such a letter of credit, which specifies in detail all the steps that must be completed by the American exporter before payment is made. If ADM complies with all the specifications in the letter of credit and submits to the Korean bank the proper documentation to prove that it has done so, the Korean bank guarantees the payment on the due date. On that date the American firm is paid by the Korean bank, not by the buyer of the goods. Therefore, all the credit risk to the exporter is absorbed by the importer's bank, which is in a good position to evaluate the creditworthiness of the importing firm. The exporter who requires a cash payment or a letter of credit from foreign buyers of marginal credit standing is likely to lose orders to competitors. Instead of risking the loss of business, American Firms can find an alternative way to reduce the risk of nonpayment by foreign customers. This alternative method consists of obtaining export credit insurance. The insurance policy provides assurance to the exporter that should the foreign customer default on payment, the insurance company will pay for the shipment. The Foreign Credit Insurance Association (FCIA), a private association of 60 U.S. insurance firms, provides this kind of insurance to exporting firms. Funding of Transactions Assistance in the funding of foreign transactions may take many forms. Eximbank (Export-Import Bank) This agency of the U.S. government facilitates the financing of U.S. exports through its various programs. In its direct loan program, the Eximbank lends money to foreign purchasers of U.S. goods, such as aircraft, electrical equipment, heavy machinery, computers, and the like. The Eximbank also purchases eligible medium-term obligations of foreign buyers of U.S. goods at a discount from face value. In this discount program, private banks and other lenders are able to rediscount (sell at a lower price) promissory notes and drafts acquired from foreign customers of U.S. firms. Loans from the Parent Company or a Sister Affiliate An apparent source of funds for a foreign affiliate is its parent company or its sister affiliates. In addition to contributing equity capital, the parent company often provides loans of varying maturities to its foreign affiliate. Although the simplest arrangement is a direct loan from the parent to the foreign subsidiary, such a loan is rarely extended because of foreign exchange risk, political risk, and tax treatment. Instead, the loans are often channeled through an intermediary to a foreign affiliate. Parallel loans and fronting loans are two examples of such indirect loan arrangements between a parent company and its foreign affiliate. A typical parallel loan arrangement is depicted in Figure 4. Figure 4 A parallel loan arrangement In this illustration of a parallel loan, an American firm that wants to lend funds to its Dutch affiliate locates a Dutch parent firm, which needs to transfer funds to its U.S. affiliate. Avoiding the exchange markets, the U.S. parent lends dollars to the Dutch affiliate in the United States, while the Dutch parent lends guilders to the American affiliate in the Netherlands. At maturity the two loans would each be repaid to the original lender. Notice that neither loan carries any foreign exchange risk in this arrangement. In essence both parent firms are providing indirect loans to their affiliates. A fronting loan is simply a parent's loan to its foreign subsidiary channeled through a financial intermediary, usually a large international bank. A schematic of a fronting loan is shown in Figure 5. Figure 5 A fronting loan arrangement In the example the U.S. parent company deposits funds in an Amsterdam bank and that bank lends the same amount to the U.S. firm's affiliate in the Netherlands. In this manner the bank fronts for the parent by extending a risk-free (fully collateralized) loan to the foreign affiliate. In the event of political turmoil, the foreign government is more likely to allow the American subsidiary to repay the loan to a large International Bank then to allow the same affiliate to repay the loan to its parent company. Thus the parent company reduces its political risk substantially by using a fronting loan instead of transferring funds directly to its foreign affiliate. Even though the parent company would prefer that its foreign subsidiary maintain its own financial arrangements, many banks are apprehensive about lending to a foreign affiliate without a parent guarantee. In fact, a large portion of bank lending to foreign affiliates is based on some sort of a guarantee by the parent firm. Usually because of its multinational reputation, the parent company has a better credit rating than its foreign affiliates. The lender advances funds on the basis of the parent's creditworthiness even though the affiliate is expected to pay back the loan. The terms of a parent guarantee may vary greatly, depending on the closeness of the parent affiliate ties, parent-lender relations, and the home country's legal jurisdiction. Eurodollar Loans The Eurodollar market is an important source of short-term loans for many multinational firms and their foreign affiliates. Eurodollars are simply U.S. dollars deposited in foreign banks. A substantial portion of these deposits are held by European branches of U.S. commercial banks. About 85 to 90% of these deposits are in the form of term deposits with the banks for a specific maturity and at a fixed interest rate. The remaining 10 to 15% of these deposits represent negotiable certificates of deposit with maturities varying from one week to five years or longer. However, maturities of 3 months, 6 months, and one year are most common in this market. Since the early 1960s, the Eurodollar market has established itself as a significant part of world credit markets. The participants in these markets are diverse in character and geographically widespread. hundreds of corporations and banks, mostly from the United States, Canada, Western Europe, and Japan, are regular borrowers and depositors in this market. The lower cost and greater credit availability of this market continues to attract borrowers. The lower borrowing costs in the Eurodollar market are often attributed to the smaller overhead costs for lending banks and the absence of a compensating balance requirement. The lending rate for borrowers in the Eurodollar market is based on the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR), which is the interest rate for large deposits, as discussed in Part 23 of this analysis. Interest rates on loans are calculated by adding premiums to this basic rate. The size of this premium varies from 0.25 percent to 0.50 percent, depending on the customer, length of the loan, size of the loan, and so on. For example, Northern Indiana Public Service Company obtained a 75 million dollar, 3-year loan from Merrill Lynch International Bank. The utility company paid 0.375 points above LIBOR for the first two years and is 0.50 points above for the final year of the loan. Over the years, borrowing in the Eurodollar market has been one-eighth to seven eighths 7/8 of a percentage point cheaper than borrowing at the U.S. prime interest rate (Block & Hirt, 2005, p. 622). During peak interest rate periods in the United States, many cost-conscious domestic borrowers flee to the Eurodollar market. Having seen this trend, in order to stay competitive, some U.S. banks offer their customers the option of taking a LIBOR-based rate in lieu of the primary rate. Lending in the Eurodollar market is done almost exclusively by commercial banks. Large Eurocurrency loans are often syndicated by a group of participating banks. The loan agreement is put together by a lead bank, known as the manager, which is usually one of the largest U.S. or European banks. The manager charges the borrower a once-and-for-all fee of commission of 0.25 percent to 1 percent of the loan value. A portion of this fee is kept by the lead bank and the remainder is shared by all the participating banks. The aim of forming a syndicate is to diversify the risk, which would be too large for any single bank to handle by itself. Multicurrency loans and revolving credit arrangements can also be negotiated in the Eurocurrency market to suit borrowers needs. Eurobond Market When long-term funds are needed, borrowing in the Eurobond market is a viable alternative for leading multinational corporations. The Eurobond issues are sold simultaneously in several national capital markets, but denominated in a currency different from that of the nation in which the bonds are issued. The most widely used currency in the Eurobond market is the U.S. dollar. Eurobond issues are underwritten by an international syndicate of banks and securities firms. Eurobonds of longer than 7 years in maturity generally have a sinking fund-provision. Disclosure requirements in the Eurobond market are much less stringent than those required by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in the United States. Furthermore, the registration costs in the Eurobond market are lower than those charged in the United States. In addition, the Eurobond market offers tax flexibility for borrowers and investors alike. All these advantages of Eurobonds enable the borrowers to raise funds at a lower cost. Nevertheless, a caveat may be in order with respect to the effective cost of borrowing in the Eurobond market. When a multinational firm borrows by issuing a foreign currency--denominated debt issue on a long-term basis, it creates transaction exposure, a kind of foreign exchange risk. If the foreign currency appreciates in value during the bond's life, the cost of servicing the debt could be prohibitively high. Many U.S. multinational firms borrowed at an approximately 7 percent coupon interest by selling Eurobonds denominated in Deutsche marks and Swiss Francs in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Nevertheless, these U.S. firms experienced an average debt service cost of approximately 13 percent, which is almost twice as much as the coupon rate. This increased cost occurred because the U.S. dollar fell with respect to these currencies. Therefore, currency selection for denominating Eurobond issues must be made with extreme care and foresight. To lessen the impact of foreign exchange risk, sometimes Eurobond issues are denominated in multicurrency units (Block & Hirt, p. 623). International Equity Markets The entire amount of equity capital comes from the parent company for a wholly-owned foreign subsidiary, but a majority of foreign affiliates are not owned completely by their parent corporations. In Malaysia, majority ownership of a foreign affiliate must be held by the local citizens. In some other countries, the parent corporations are allowed to own their affiliates completely in the initial stages, but they are required to relinquish partial ownership to local citizens after 5 or 7 years. To avoid nationalistic reactions to wholly-owned foreign subsidiaries, such multinational firms as ExxonMobil, General Motors, Ford, and IBM sell shares to worldwide stock holders. It is also believed that widespread foreign ownership of the firm's a common stock encourages the loyalty of foreign stockholders and employees toward the firm. Thus selling common stock to residents of foreign countries is not only an important financing strategy, but it is also a risk-minimizing strategy for many multinational corporations. A well-functioning secondary market is essential to entice investors into owning shares. To attract investors from all over the world, reputable multinational firms list their shares on major stock exchanges around the world. Many foreign corporations, accommodate American investors by issuing American Depository Receipts (ADRs). All the American-owned shares of a foreign company are placed in trust in a major U.S. Bank. The bank, in turn, will issue its depository receipts to the American stockholders and will maintain a stockholder ledger on these receipts, thus enabling the holders of ADRs to sell or otherwise transfer them as easily as they transfer any American company shares. ADR prices tend to move in a parallel path with the prices of the underlying securities in their home markets. Looking elsewhere around the world, U.S. firms have listed their shares on the Toronto Stock Exchange and the Montreal Exchange. Similarly, more than 100 U.S. firms have listed their shares on the London Stock Exchange (Block & Hirt, 2005). To obtain exposure in an international financial community, listing securities on world stock exchanges is a step in the right direction for a multinational firm. This international exposure also brings an additional responsibility for the MNC to understand the preferences and needs of heterogeneous groups of investors of various nationalities. The MNC may have to print and circulate its annual financial statements in many languages. Foreign investors are more risk-averse than their counterparts in the United States and prefer dividend income over less certain capital gains. Common stock ownership among individuals in countries like Japan and Norway is relatively insignificant, with financial institutions holding substantial amounts of common stock issues. Institutional practices around the globe also vary significantly when it comes to issuing new securities. Unlike the United States, European commercial banks play a dominant role in the securities business. They underwrite stock issues, managed portfolios, vote the stock they hold in trust accounts, and hold directorships on company boards. In Germany the banks also run an over-the-counter market in many stocks. The International Finance Corporation Whenever a multinational company has difficulty raising equity capital due to lack of adequate private risk capital in a foreign country, the firm may explore the possibility of selling partial ownership to the International Finance Corporation (IFC). This is a unit of the World Bank Group. the International Finance Corporation was established in 1956, and it is owned by 185 member countries of the World Bank (ifc.com). Its objective is to further economic development by promoting private enterprises in these countries. The profitability of a project and its potential benefit to the host country's economy are the two criteria the IFC uses to decide whether to assist a venture. The IFC participates in private enterprise through buying equity shares of a business, providing long-term loans, or a combination of the two for up to 25 percent of the total capital. The IFC expects the other partners to assume managerial responsibility, and it does not exercise its voting rights as a stockholder. The IFC helps finance new ventures as well as the expansion of existing ones in a variety of industries. Once the venture is well-established, the IFC sells its investment position to private investors to free up its capital. *MAIN SOURCE: BLOCK & HIRT, 2005, FOUNDATIONS OF FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT, 11TH ED., PP. 620-625* end |

No comments:

Post a Comment