January is always a good month for behavioral economics: Few things illustrate self-control as vividly as New Year's resolutions. February is even better, though, because it lets us study why so many of those resolutions are broken.

Demand, Supply, and Market Equilibrium

(Part A)

by

Charles Lamson

|

Parts 1 through 8 of this analysis introduced the discipline, methodology, and subject matter of economics. We now begin the task of analyzing how a market economy actually works. The next several posts present an overview of the way individual markets work. They introduce some of the concepts needed to understand both microeconomics and macroeconomics.

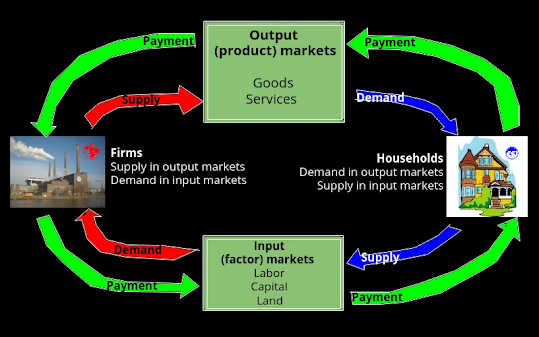

As we proceed to define terms and make assumptions, it is important to keep in mind what we are doing. In Part 3 of this analysis, I explained what economic theory attempts to do. Theories are abstract representations of reality, like a map that represents a city. I believe that the models presented here will help you understand the workings of the economy as a map helps you find your way around a city. Just as a map presents one view of the world, so too does any given theory of the economy. Alternatives exist to the theory that is presented. I believe, however, that the basic model presented here, while sometimes abstract, is useful in gaining an understanding of how the economy works. In the simple island society presented in Parts 5 and 7, Bill and Colleen solved the economic problem directly. They allocated their time and used the island's resources to satisfy their wants. Bill might be a farmer, Colleen a hunter and carpenter. He might be a civil engineer, she a doctor. Exchange occurred, but complex markets were not necessary. In societies of many people, however, production must be satisfy wide-ranging tastes and preferences. Producers therefore specialize. Farmers produce more food than they can eat to sell it to buy manufactured goods. Physicians are paid for specialized services, as are attorneys, construction workers, and editors. When there is specialization, there must be exchange, and markets are the institutions through which exchange takes place. In the next few posts we begin to explore the basic forces at work in market systems. The purpose of our discussion is to explain how the individual decisions of households and firms together, without any central planning or direction, answer the three basic questions: what gets produced, how is it produced, and who gets what is produced? We begin with some definitions. Firms and Households: The Basic Decision-Making Units Throughout this analysis, we will discuss and analyze the behavior of two fundamental decision-making units: firms---the primary producing units in an economy---and households---the consuming units in an economy. Both are made up of people performing different functions and playing different roles. in essence, what we are developing is a theory of human behavior. A firm exists when a person or group of people decides to produce a product or products by transforming inputs---that is, resources in the broadest sense---into outputs, the products that are sold in the market. Some firms produce goods; others produce services. Some are large, many are small, and some are in between. All firms exist to transform resources into things that people want. Most firms exist to make a profit. They engage in production because they can sell their product for more than it costs to produce it. The analysis of firm behavior that follows rests on the assumption that firms make decisions in order to maximize profits. An entrepreneur is one who organizes, manages, and assumes the risks of a firm. When a new firm is created, someone must organize the new firm, arrange financing, hire employees, and take risks. That person is an entrepreneur. Sometimes existing companies introduce new products, and sometimes new firms develop or improve on an old idea, but at the root of it all is entrepreneurship, which some see as the core of the free market enterprise system. Without entrepreneurship, the free enterprise system breaks down. The consuming units in an economy are households. A household may consist of any number of people: a single person living alone, a married couple with four children, or 15 unrelated people sharing a house. Household decisions are presumably based on individual tastes and preferences. The household buys what it wants and can afford. In a large, heterogeneous, and open society such as the United States, widely different tastes find expression in the marketplace. A six-block walk in any direction on any street in Manhattan or a drive from the Chicago Loop south into rural Illinois should be enough to convince someone that it is difficult to generalize about what people like and do not like. Even though households have wide-ranging preferences, they also have some things in common. All---even the very rich---have ultimately limited incomes, and all must pay in some way for the things they consume. Although households may have some control over their incomes---they can work more hours or fewer hours---they are also constrained by the availability of jobs, current wages, their own abilities, and their accumulated and inherited wealth (or lack thereof). Input Markets and Output Markets: The Circular Flow Households and firms interact in two basic kinds of markets: product (or output) markets and input (or factor) markets. Goods and services that are intended for use by households are exchanged in product or output markets. In output markets firms supply and households demand. To produce goods and services, firms must buy resources in input or factor markets. Firms buy inputs from households, which supply these inputs. When a firm decides how much to produce (supply) in output markets, it must simultaneously decide how much of each input it needs to produce the desired level of output. To produce automobiles, Ford Motor Company must use many inputs, including tires, steel, complicated machinery, and many different kinds of labor. Figure 1 shows the circular flow of economic activity through a simple a market economy. Note that the flow reflects the direction in which goods and services flow through input and output markets. For example, goods and services flow from firms to households through output markets. Labor services flow from households to firms through input markets. Payment (most often in money form) for goods and services flows in the opposite direction. In input markets, households supply resources. Most households earn their incomes by working---they supply their labor in the labor market to firms that demand labor and pay workers for their time and skills. Households may also loan their accumulated or inherited savings to firms for interest, or exchange those savings for claims to future profits, as when a household buys corporate bonds or shares of stock in a corporation. In the capital market, households supply the funds that firms used to buy capital goods. Households may also supply land or other real property in exchange for rent in the land market. Inputs into the production process are also called factors of production. Land, labor, and capital are the three key factors of production. Throughout this analysis, the terms input and factor of production will be used interchangeably. Thus, input markets and factor markets mean the same thing. Early economics texts included entrepreneurship as a type of input, just like land, labor, and capitol. Treating entrepreneurship as a separate factor of production has fallen out of favor, however, partially because it is unmeasurable. Most economists today implicitly assume that it is in plentiful supply. That is, if profit opportunities exist, it is likely that entrepreneurs will crop up to take advantage of them. This is assumption has turned out to be a good predictor of actual economic behavior and performance. The supply of inputs and their prices ultimately determines household income. The amount of income a household earns depends on the decisions it makes concerning what types of inputs it chooses to supply. Whether to stay in school, how much and what kind of training to get, whether to start a business, how many hours to work, whether to work at all, and how to invest savings are all household decisions that affect income. Input and output markets are connected through the behavior of both firms and households. Firms determine the quantities and character of outputs produced and the types of quantities of inputs demanded. Households determine the types and quantities of products demanded and the quantities and types of inputs supplied. The following analysis of demand and supply that is presented in the next post will lead up to a theory of how market prices are determined. Prices are determined by the interaction between demanders and suppliers. To understand this interaction, we first need to know how product prices influence the behavior of demanders and suppliers separately. We therefore discuss output markets by focusing first on the demanders, then on suppliers, and finally on the interaction. *MAIN SOURCE: CASE & FAIR, 2004, PRINCIPLES OF ECONOMICS, 7TH ED., PP. 43-46* end |

No comments:

Post a Comment